|

Regional History to 1275 A.D. 4 of 4 installments by Thomas Frascella Although there is no evidence of permanent settlement or structures within the confines of the Comune di San Fele before the year 966 A.D., the general region has witnessed an extraordinary passage of people and cultures throughout time. Caves within the Appenines above the neighboring towns of Bella and Muro Lucano contain primitive drawings, giving evidence of human visitation to this area in Italy’s prehistoric past. The first major major group to take up

residence and dominate the region was the ancient Samnites. This cultural and

ethnic group is credited with establishing many early settlements in the region

including the original settlement of Naples. Researchers believe that traces of

the ancient Samnite language can be heard in the dialect of a number of local

communities including that of neighboring Muro Lucano. Samnite culture and people were overcome and absorbed by the colonial efforts of the ancient Greeks about 2700 years ago. Ancient Greek culture and language came to dominate southern Italy and Sicily and much of the ancient population settled directly from ancient Greece. In fact, southern Italy and Sicily were considered a part of greater Greece in the ancient world. Many famous ancient “Greek” artists, mathematicians and philosophers were actually born or lived in southern Italy or Sicily during the height of the Ancient Greek Empire. It is during this period that the mountainous region of the Appenines was first referred to as Italia, referring to the abundance of cattle raised in the rich pasture land of the valleys of the region. Eventually the ancients extended the name Italia to refer to the entire peninsula. The first cultivation of grapes and the production of wine were introduced by the ancient Greek colonists of that time. Wine production and the wine variety of the region traces back to the varieties introduced by the Greeks, and are of the oldest type in Italy. The neighboring town of Bella is said to have developed as part of the trading routes of the Greeks who frequently used the Crocelle Pass. As a result of the influence of ancient Greek culture in the area this region of Italy is said to have developed the first distinctly Italian form of literature. The so called “Atellan Farce” developed in the town of Atella, not far from present day Naples or San Fele. Although no ancient Greek ruins exist in San Fele, some of the best preserved Greek temples and structures in the world are to be found throughout southern Italy and Sicily. As the Greek Empire declined the Roman Empire rose. The Romans considered southern Italy a conquered “foreign” province. Throughout the Roman period Greek was as commonly spoken as Latin in the south. In the city of Naples, Greek was officially the primary language of the city throughout the Roman era. The Emperor Nero is said to have traveled south to the city of Naples to perform his plays and poems which he rendered in Greek, not Latin. The contributions of the region to the Roman era are often overlooked. Many famous Roman architects, mathematicians, philosophers and artists were actually born in the south, just as had been the case in ancient Greece. The south also suffered as a result of often supporting interests other than those of Rome during this period. The armies of Hannibal and the slave army of Spartacus found friendly refuge in the mountains and valleys of the region. The neighboring town of Muro Lucano is the site of a famous Roman defeat at the hands of Hannibal during the second Punic War. It is during the Roman era that the region received the name Lucania. The name refers to the lush forests that covered the mountains at the time. During the so called “Dark Ages”, after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century A.D., the region came under the Eastern Roman Empire’s control which governed through the introduction of Lombard vassals. For much of the 8th thru 10th centuries the area that is now San Fele existed as the uninhabited eastern edge of the Lombard duchy of Salerno. It is during this 500 year period that the region acquired its present name of Basilicata from the Greek “Basil”. The sylvan, uninhabited character of the immediate area that would become San Fele, however, changed abruptly in the year 966 A.D.

The Beginning of San Fele (966-1250) For a brief thirty year period in the mid 10th century the forces of the German Kings and Holy Roman Emperor Otto I and Otto II attempted to seize control, from the Byzantine Empire, of the southern region of Italy. It is during this period that Otto I commissioned the building of a defensive fortress at the summit of Monte Castello. The purpose of the fortification was to guard against a Byzantine counter-offensive through the Crocelle Pass. The fortress, constructed between 966 and 969 A.D., is believed to be the first structure erected in the area that is now San Fele. San Fele officials generally mark the year 966 A.D. as the community’s founding date. It is known that the fortress was abandoned by 986 A.D. when the efforts at control by Otto II were met with defeat and the region passed back to the jurisdiction of the Duke of Salerno, who served as a vassal to the Byzantine Empire. It is while under the control of the German Kings of this period the fortress also began a long history of holding important political prisoners. San Fele may well have never come to be and the Dukes of Salerno would be little known and less remembered if not for an events that occurred thirty years later in 1016 A.D. In that year the town of Salerno was violently attacked by Saracen pirates. The attack by a force of hundreds of pirates was well on its way to success when an unexpected counter attack was launched by a group of fewer than twenty pilgrims who had lodged in the town, having just returned from a visit to the holy places of Jerusalem. To the astonishment of both the Saracens and the defenders of the town, these pilgrims rained slaughter down upon the vastly superior pirate force, causing panic and flight. It was in this engagement that Italy was introduced to a new type of warrior the Norman Knight. The Duke went on to offer these knights a contract as mercenary soldiers. Historians regard this event as both the introduction of the Normans into southern Italy and the event that marks the end of the “Dark Ages” of Europe. In 1034 advisors to the Byzantine Emperor determined that an opportunity existed to invade and recapture Sicily, which had been under Saracen control for about two hundred years. Plans were drawn up, an army was raised and training began. A demand was sent to the Lombard Dukes to supply 3500 soldiers and 300 Norman knights to supplement the Emperor’s army once it arrived in Italy. The Lombard Dukes, as vassals to the Emperor, had little or no choice although 300 knights were roughly all of the Norman force that was in Italy at the time. Instead of turning over their knights as expected, they recruited an additional 300 Normans knights for duty with the invasion force. Once recruited and before the invasion commenced, this new force of Normans proved difficult for the Lombard Dukes to control. It was determined that the force should be divided among 12 senior Norman captains and distributed to isolated mountain locations far removed from significant population centers. In 1036 a contingent of Norman mercenaries was dispatched by the Duke of Salerno to garrison the abandoned fortress that Otto I had built atop Monte Castello. The mercenaries were also given the task of guarding a small number of Lombard Milanese political hostages who were being held by the Duke of Salerno as a favor to his cousin the Lombard archbishop of Milan. It is in the dispatches issued by the garrison commander in 1036 that the location is first recorded and referred to as “Fele”. The term Fele in the official histories of the town is acknowledged to have an uncertain meaning. There is general agreement that Fele is a foreign, not Latin-based, word. Today in modern Italian the word is pronounced ( Fay-Lay). However in the traditional dialect of the town the word was pronounced ( Fell ). It should be noted that in 10th and 11th century Norman/French there was in use a word "Fel", less often spelled Fele, pronounced (Fell ) which the Norman military applied to very specific locations. In order to qualify as a Norman Fel, a location must be of a significant height and the height must be of a scraggy character. The height must also occupy a strategic location where a defensive fortification should be. Interestingly, modern texts describe the surface of Monte Castello in Italian by the word “scraggio”. In English, the modern word Fell when used as a noun derives from the Norman/French language and continues to be applied to the names of places as in Essex Fells or Fells Point in New Jersey. In the year 1038 the Byzantine preparations for invasion of Sicily were completed, their army was assembled in Italy and the Italian and Norman supporting troops ordered to report. In this year the Milanese political hostages being held at the Fele were released and the garrison removed from the fortress. It is believed that due to a plague striking the city of Milan the hostages decided to remain in the otherwise uninhabited Vitalba Valley. It is recorded that they married local women from nearby villages and established the beginnings of the community which would develop into San Fele.A number of San Fele families trace their ancestry to these original Lombard settlers including, the Faggella, Thomasulo and Muccia families. In 1040 a dispute erupted over compensation for services between the Byzantine commander and the Norman knights resulting in the Normans quitting the Sicilian campaign followed by the Italian troops. Within two years a coalition of Norman lead Italians had begun a rebellion and had succeeded in defeating two vastly superior Byzantine armies sent to crush them. The Normans directed their military efforts from the central Appenines, where they launched their campaign first against the Byzantines and then against the independent Italians cities of the south. Headquartered in the mountain fortress at Melfi, about twenty-five miles from San Fele, the Normans recognized that control of the mountain passes effectively divided the peninsula to their advantage. In 1042 the Lombard Duke of Salerno granted hereditary control of Melfi to the Norman Baron William “Iron Arm” Hauteville. In the campaigns in southern Italy that followed, the Normans honed both their battle tactics and their use of inter-supporting fortresses to great success. The Normans were so successful that by 1059 they had extracted from the Holy Roman Emperor and from the Pope recognition of their right to govern southern Italy and Saracen held Sicily. The Normans invaded Sicily in 1060. Lessons learned in southern Italy by the Normans are credited with being the basis of the success of the Norman Duke William in his invasion of England in 1066. By the mid 1070s all of southern Italy was under the control of the Italian Normans and by 1090 the same became true of Sicily. The territory was divided among the Norman elite into feudal baronies. The Fele, composed of roughly the boundaries of the present Comune di San Fele, was established at this time. A Norman Baron and Norman garrison were then invested in the fortress atop Monte Castello. Throughout the period of the Norman take over of southern Italy Norman presence at Monte Castello was focused as military support. The area lacked sufficient economic resources to develop as a commercial or village center. As previously stated descendants of many of the families of San Fele can trace their ancestry to either the early Lombard settlers or the Norman knights garrisoned at the fortress. The early culture, activities and history reflect a military heritage as one would expect from a military base. World politics began to effect the development of the community when, in1096, the Pope called upon European warriors to reclaim Jerusalem from Moslem control. Suddenly, the fortress found itself on one of the Crusader/Pilgrim routes and for the next four hundred years traffic arising from these wars dominated the culture and economics of the community. The success of the First Crusade is largely attributable to the fighting skill and leadership of the Norman Knights, in particular Norman/Italian Knights who participated. Many histories also mention that shortly after the capture of Jerusalem, a military order was formed for the protection of Pilgrim routes. The organization was known as the Knights Templar, usually described as founded by a French Knight by the name of Hugh de Payens. Vatican records indicate with more specificity that the Templars were founded by a Norman/Italian Knight by the name of Hugh de Paganis born in Nocera, Italy. Nocera was a Norman barony located about twenty-five miles northwest of San Fele.

The first church of San Fele was also built about this time and was located just beyond the outer walls of the fortress. The site is now occupied by the Palazzo Frascella. The church, like the fortress, was destroyed in a15thcentury earthquake which struck the village. Historical accounts state that the church was built in Norman style, with a detached round bell-tower. Devotion at the church was centered on Saints Sebastian and Nicholas, both early Italian-Norman favorites. By the year 1125 Count Roger Hauteville had begun to consolidate his power in the Norman controlled South. Roger’s ultimate goal was to establish an independent Kingdom under his authority in southern Italy. About this time, villagers from a coastal community arrived in the Barony to remove a statue of the Madonna and child. The statue had been secreted in a cave on Mt. Pierno in order to protect it from Saracen coastal raids. The San Felese had been unaware of the statue’s presence until after it was removed. According to local legend shortly after the statue’s departure, by “miraculous” intervention, the statue was returned to the cave where it had previously resided.Also according to local legend during the next decade or so the statue was removed several more times however each removal met with a miraculous return. In the year 1139 under the oversight of the hermit monk St. William Vercelli possession of the statue was established permanently at Pierno with the San Felese required to build a small chapel to house the statue and a modest hostel to service Pilgrim and Crusader travelers on the site. 1139 is also the year in which the decade old civil war for control of southern Italy ended with the decisive victory of Count Roger’s forces over the Papal lead forces of Innocent II. Roger was crowned King of southern Italy by Innocent II in Palermo in 1140 approximately three months after Innocent’s forces had been annihilated and he himself captured by the Normans. Celebration of the establishment of Pierno as the permanent location of the Madonna statue has been held annually in August since 1140. As part of the celebration the statue is removed from the 12th century church and carried away and returned in remembrance of those times when the statue had been taken. The local inhabitants follow behind the statue carrying olive branches and oak twigs bent and twisted into the form of an oval.The Town’s history records the first written reference with “san” added to Fele as occurring in 1155. In that year an official census document initiated by King Roger I but finished during the reign of his son William I was published. Written in Latin and called “The Catalogue of the Norman Baronies” the document refers to San Fele as “Sanctus Felis”. The purpose of the census was to record the tangible value of all of the communities in order to properly assess a war tax and manpower requirement from each. In the year 1186 the City of Jerusalem was retaken by Moslem forces. This event launched what is referred to as the 3rd Crusade 1186-1193. It appears that just prior to the events of 1186 unfolding a political alliance between King William II of Southern Italy and Frederick I von Hohenstaufen was struck. To solidify the non aggression pact several Hohenstaufen women were married to very minor nobles in southern Italy and Constance Hauteville was married to Henry Von Hohenstaufen. The barony of San Fele appears to have been among those entities involved in pact. When the Pope called for the 3rd Crusade in 1186 both William and Frederick immediately pledged Crusade in support. William II sent troops in 1186 to reinforce the ports of Acre and Tyre. Frederick I although 66 years of age assembled a massive army commanded by the members of his royal house and began to march to the Holy Land in 1187.The Baron

Tancred of

San Fele also appears to have taken up the Crusader cause in 1186

and further pledged that if he and his men should succeed on their

adventure and return safely that he would build a new Church on the

site of the Chapel to the Madonna. According to the dates ascribed

the Baron left on Crusade in 1187 and returned safely in 1189. He

then began to fulfill his pledge of constructing the new Church in

that same year. Frederick I died while on Crusade, drowning by

falling from his horse while crossing a river in

1189. His son Henry succeeded him as Holy Roman Emperor and King of Germany in

1190. William II died without heir also in 1189 and after a brief contest over

succession Constance was crowned Queen of southern Italy with the Holy Roman

Emperor Henry as her consort in 1194. Together they had one son Frederick Roger

von Hohenstaufen born in 1193.

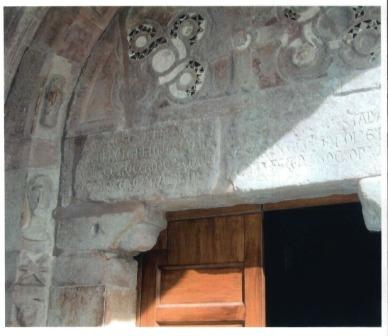

The building of the Church of the Madonna Di Pierno continued from 1189 thru 1198. The Church was designed by the Norman-Italian architect Serlo and is in the Norman style. At some point during its nine year construction the cost of the building was assumed by the local Count of Balvano, the county in which San Fele rests. The story of the construction of the Church is carved in both Latin and Norman pictographs over the main entrance to the Church. Although completed in 1198 the Church was not consecrated until 1225.

The Holy Roman Emperor

Henry died in 1197 while preparing to leave on what was to become

the 4th Crusade. A contest for the Emperor’s crown in

Germany followed Henry’s death. Queen Constance unable to press for

her four year old son’s claim and fearing for his safety abdicated

young Frederick’s claim to the German crown in favor of his uncle.

In exchange his uncle and the Pope pledged protection of young

Frederick who retained only his right to

In 1198 Queen Constance died leaving young Frederick an orphan of five years of age under the guardianship of the Pope and living in Palermo. Frederick’s tutelage under the monks assigned to his education was quite unusual for the time and the young Frederick apparently flourished in the intellectual diversity of the Sicily of that period. It is reported that by the time of his first arranged marriage at the age of fourteen Frederick was fluent in nine languages and fully literate in seven. He was also known to engage in correspondence with scholars on a number of subjects usually in the native language of the scholar. In 1205 Frederick’s uncle died without heir opening up the crown of Germany to a rival house. Upon reaching his majority in 1211 Frederick with the encouragement of the Pope lead an army northward to reclaim his crown as King of Germany, which he accomplished in 1215. By 1220 Frederick had returned to Italy where he was installed in Rome as the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. Following the collapse of the poorly lead 5th Crusade 1220 which Frederick sent soldiers to but did not himself participate the Pope began to lobby Frederick to take up the Crusade himself. Frederick resisted the Pope for five years until the proposition was enhanced by the arrangement of a marriage between the widowed Frederick and Yolande of Brienne the heir to the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Also in 1225 the small Church of the Madonna Di Pierno was finally consecrated. Officiating at the Mass of Consecration was the Pope and in attendance the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. Although Frederick’s Crusade was successful in regaining Jerusalem his relationship with the new Pope starting in 1227 was not. In fact Frederick was excommunicated twice by the Pope during the Crusade itself. Upon his return to Europe, Frederick found many factions of his Empire in opposition if not rebellion. In 1232 his 21 year old son Henry, who he had installed as co-regent of Germany and Sicily allied with the Lombards in open rebellion. Frederick put down the rebellion and arrested his son in 1234 replacing him as co-regent with Henry’s younger half brother Conrad. In this era most regents would have dealt with a treasonous son by execution, arrest and imprisonment would have been regarded as sentimental and weak. However, Frederick defied convention and had his son removed to the County of Melfi, specifically San Fele. It is in San Fele that Henry spent the majority of the remaining eight years of his life. Shortly, before what would become Henry’s death, Frederick ordered his son slowly moved eastward and history mentions only that in 1242 Henry fell to his death from a mountain top either the result of a failed attempt at escape, a suicide, or upon the order of Frederick. Histories generally do not mention what recent forensic examination of Henry’s crypt in Canosa confirms, that Henry at the time of his “fall” was very near death due to advanced Leprosy 3. Examination of Henry’s skeleton confirmed that Henry’s nasal passage, jaw, lower legs and ankles were all severely ravaged by the disease at the time of his death. Henry was physically incapable of escape and the slow movement eastward must have been both painful and difficult because of his overall health. An interesting historical question might be to what purpose did Frederick send his dying son eastward in the company of family members? By the late 1240’s a constant state of warfare had greatly reduced the number of male members of the Hohenstaufen extended family. By Imperial edict Frederick granted those males who could demonstrate descent from Hohenstaufen females the right to be considered Hohenstaufen. This is the point that Italian documents begin referring to several Norman/Italian families as Hohenstaufen. On the San Fele website the crest showing the Imperial Hohenstaufen double headed eagle flanked by two six-pointed starbursts reflects this status. Frederick II died in 1250.

With the death of Frederick II in 1250 the book closes on a truly unique monarch and a man well ahead of his political time. It is worthwhile to list some of the accomplishments of this great king and man who considered our ancestral region of Italy the Vulture as home. These accomplishments include:

1. The founding of the University of Naples now called Frederico Secundo University. 2. The encouragement and patronage of the first Italian based school of Literature, Sicilian dialect. 3. The first formal training programs for municipal administrators. 4. The most advanced centralized codification of Laws for its time known as “The Constitution of Melfi”. 5. Authorship of what is regarded as the first modern scientific treatise. Written on the subject of his favorite pastime the breeding and training of hunting falcons. 6. The introduction of Arabic numerals and the concept of mathematical zero into European science and commerce. 7. The separation of the practice of pharmacy from the practice of medicine, in effect forcing the sharing of medicinal “cures”. 8. The encouragement of full integration of the various cultures and races of his kingdom in the participation of his government without regard to religious beliefs. 9. Frederick was the last European King to hold the city of Jerusalem. He obtained the city by political negotiation not conquest although he had the military power to do otherwise. During his reign he allowed the practice of all three bible based faiths to be conducted within the city. 10. For some of the above he was excommunicated by several successive Popes three or four times.

The integration that he encouraged ultimately was considered by the Church a threat to Papal authority. From about 1230 on the Church actively undermined Frederick’s authority, encouraged rivals and sought to weaken his position by operation of fiats of excommunication which applied not only to Frederick but to all of his subjects. Frederick’s vision of an integrated society to some extent helped him survive but drained his resources. At one point Frederick installed a large community of loyal Moslem Saracens defensively north of Melfi at Lucera. The Saracens served as his personal guard and were unaffected by the excommunications.

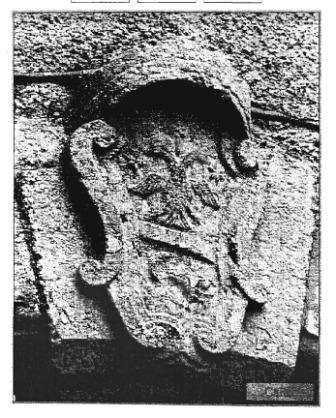

Basilicata and the Vulture region of Italy have a remarkable and long history of tolerance and blending of peoples, cultures and religious beliefs. I have mentioned that among the dominate ancient peoples and cultures to settle in the region were the Samnites, Greeks, Romans, Lombards and Normans. However,I have not yet described the contribution of the Jews to regional culture and history. As the area of the Vulture sits amidst the trade routes of the ancient world, history records that among the peoples of the area were small enclaves of Jewish merchants originating back to the period of the ancient Greeks some 2,300 years. The best known of these Jewish enclaves, as understood from ancient records, was the community that lived in the town the Romans called Venosium, today modern Venosa. Although a small community in number the Jewish merchants of Venosium were a prosperous community well integrated within the Greco/Roman culture of the Province of Lucania. The dynamics of the community abruptly changed shortly after the “Jewish Revolt” of the first century. Following the Roman victory, historians estimate that between 50,000-80,000 captive Jews, many from Jerusalem itself, were brought as slaves to Italy mostly to Rome and Sicily. At some point some 5,000 of the Jewish slaves in Rome were purchased, many by the Jewish community in Venosium, and removed to that location. Therefore by the second century the Jewish population of the Vulture was and would remain by percentage the highest in Italy. It appears that the Jewish population fully blended with the pre-existing population with full access to all levels of local Greco/Roman society. Interestingly as Western Roman power diminished in the fourth and fifth centuries a resurgence of the use of Hebrew is noted in the burial sites in the Venosium. It is now understood that by the seventh and eighth centuries schools where Hebrew was taught and used as a living language had been well established early on in this region of Italy. A number of Jewish texts that were long thought to have come from the Jews of Spain in the eleventh century are now believed to actually have been written in Italy in the seventh and eighth centuries. Today Venosium is credited by modern scholars as the location which preserved Hebrew as a living and spoken language. Archeologists recently have discovered that the Jewish catacombs of Venosa probably if excavated would represent the oldest and largest Jewish cemetery outside of Israel, evidencing use from approximately 300 B.C. to 1500 A.D. The community of Venosium connects to the history of San Fele from its very beginning. When Otto the Great ordered the construction of the fortress atop Monte Castello his forces conscripted the labor from Venosium to build it in 966. Later with the arrival of the Normans, the Norman fortress at Melfi was also constructed with labor from Venosium. When Roger I sought to gather medical texts from ancient sources for what would propel the University of Salerno as the first University to be created after the Dark Ages the Jewish translations and medical texts were delivered from Venosium. Jews in the Volture would continue to serve fully in the service of the Norman and Hohenstaufen dynasties of southern Italy. In fact, up until the end of the Hohenstaufen rule Jewish ancestry was openly declared as readily as any other ethnic origin in the region without fear of persecution or discrimination. A number of noble families in the region incorporated into their coat of arms symbols expressing that they had Jewish as well as other ethnic ancestry.

Fortress at Melfi

At the time of Frederick Il's death in 1250 the Empire had erupted in regional civil war. This warfare encouraged by the Popes and various pro Papal allies had largely been held at bay by Frederick II but the tide began to turn at his death. Frederick had just prior to his demise divided his territories under the management of three of his sons. The three sons in order of age were the illegitimate Enzo named King of Sardinia and vicar of the Lombard States, Conrad the oldest legitimate son and anticipated successor as King of Germany and Conrad's younger half brother Manfred who was Vicar of southern ltaly and Sicily. Enzo was captured in 1249 in northern ltaly shortly before Frederick's death and would remain a prisoner in Bologna for the rest of his life. In 1245 Pope Innocent IV had attempted to undermine Frederick's authority by declaring his son Conrad deposed as King of Germany and installing an anti-King. At the age of twenty-two Conrad succeeded his father in 1250 but was denied the Title Holy Roman Emperor and his right to the kingship of Germany continued to be disputed by the Papacy. As a result he was forced to continue the struggle against the Papal aligned forces known as Guelphs in Germany and northern Italy. In 1252 Conrad became the father of his first and only son whom he named Conradin. While this was occurring Manfred despite his youth, eighteen in 1250, was largely successful with the aid of loyal Hohenstaufen supporters, called Ghibelline, to consolidate Hohenstaufen authority in the south of Italy. Everywhere that is except the rebellious city of Naples. San Fele remained loyal to the Ghibelline or Hohenstaufen cause. It is during this period that the town in a demonstration of support adopted the extremely rare Heraldic emblem known as a "Capo dell' Impero".

In 1253 Conrad lead his forces southward in an assault on Naples forcing the city to capitulate. His victory was however short lived as Conrad contracted malaria and died in Lavello, Basilicata in 1254. Manfred accepted the role of regent on behalf of his two year old nephew Conradin and the struggle of Guelph vs. Ghibelline continued. As it progressed Manfred would be excommunicated by a succession of Popes but generally held his own until around 1262.Between 1257and 1262 Manfred consolidated his power in both the northern and southern regions of ltaly at one point he had himself declared King of Sicily, as it was rumored that Conradin had died in Germany. Manfred’s first marriage to Beatrice of Savoy produced a daughter Constance. After the death of his first wife he married Helena daughter of Michael II Komnenos Doukas. Manfred’s military victories in the north in support of Siena, the arraignment of the marriage of his daughter to Peter Ill King of Spanish Aragon in 1262 and his own marriage alliance to the Byzantine Empire represented the high points of Manfred’s attempt to reunite his father’s Empire. However Pope Urban IV struck upon a new tactic by declaring Manfred once again excommunicate and the kingship of Southern Italy vacant. The Pope first offered the Kingship of Southern Italy to the King of England who declined but then found a more willing buyer in the King of France. In 1263 the Pope declared Charles of Anjou, younger brother of the King of France as Charles I King of Southern Italy. In 1265 Charles marched into ltaly at the head of a thirty thousand man French army to challenge Manfred. In the interim Conradin by then eleven, had slipped out of Germany and had also sought the protection of southern Italy. In February 1266 the forces of Charles and the forces of Manfred met in Benevento. Ghibelline forces from the Vulture would probably have been lead by Manfred's uncle Galvano Lancia who he had appointed Duke of Salerno, the name Lanza is a derivative of Lancia. A number of conflicting historical reports on the battle exist however it appears that Manfred's forces were succeeding when Manfred exposed himself to the fighting and was killed. Without their leader the Ghibelline forces collapsed and the forces of Charles I took the field and the victory. The Guelph forces of Charles I followed this victory in 1267 by the capture of Conradin. With the execution of Conradin in 1268 and the era of the House of Anjou or in Italian Angivin begins in southern Italy. It also marks the beginning of a period of very close alliance between the papacy and the French Royal House. Although the Ghibelline forces were defeated and without cohesive leadership they still represented a significant opposition to the Guelph coalition that was then consolidating its position. At the urging of the PopeGhibelline strongholds were encouraged to be crushed or destroyed and male members of the Hohenstaufen family exterminated. In 1268. Manfred's second wife Helena was imprisoned where she died in 1271. During this period tens if not hundred's of thousands of Italian Ghibellines lost their lives and many cities were ravaged and towns annihilated throughout Italy. Some of the atrocities of this period would create vendettas between cities and families which would carry forward for hundreds of years. Around 1270 Charles I began a campaign to root out the Ghibelline strongholds in his southern Italian territory and dispatched troops to exterminate the population of several towns and villages including the town of San Fele. As our San Felese ancestors watched the destruction and massacre of the populations of several towns in the region they realized that they could not survive a siege of their fortress. What occurred next is truly extraordinary. Faced with certain death they removed the entire population into the mountains and forests that surrounded San Fele at that time. When the Angivin army arrived they found everyone gone and when they tried to follow in the rugged and unyielding terrain they were greeted with ambush and death from hit and run tactics. Apparently the tactic was extremely effective, in that it forced the Angivin's to maintain troops in a remote area which were badly needed in other parts of the Angivin Kingdom. With the execution of Enzo in 1272, the last of the male Hohenstaufen royals was dead. In Germany the establishment of the Hapsburg dynasty in 1273 sufficiently reduced the threat of any meaningful Hohenstaufen lead military counter strike and appears to have created an opportunity to establish a truce between the San Felese and the Angivin. The Angivins agreed to forego attempting to annihilate the population and the San Felese agreed to pay a "Peace Tax". Of note, the San Felese must have made enough of an impression that the collection of the Peace Tax was to be carried out by the Knights of St. John not by the Angivin forces. I believe the resistance and flight to the hills tactic engaged by the San Felese in the above circumstance may be the earliest example of the successful use of the tactic in southern Italy. There would be numerous later examples where the resident populations were declared outlaw by both the Church and the foreign ruling government but the San Felese stand was among the most successful. Whenever I review the above incident I am reminded of a story I was told by the late Dominic Frascella a long time member of our organization. He related that as a young man he found himself In an advance U. S, infantry unit fighting its way up the Italian peninsula in the area of San Fele. He said that his unit actually got the assignment to be the first unit in to "liberate" the town. He said that he recognized the name of the town when the orders were given and was excited to enter the town. As it had already been several generations since our family had immigrated he wondered if we had any family there and how he would be greeted. However, he was disappointed when they arrived as the town was deserted. He presumed everyone was up in the mountains waiting for the Germans and Americans to move on. It should be noted that around 1273 the myth that the Hohenstaufens and in particular Frederick would rise again forming a new era of German unity began. The myth may have affected the only remaining threat to the coalition of power assembled on behalf of the Papacy. That threat was in the person of a southern Italian priest and teacher who on his mother's side was a descendant of the marriage alliances formed between Fredrick I and the Hautevilles in 1184.The priests name was Thomas of Aquine born in 1225.So powerful a figure was Aquinas that there was speculation that he might eventually be elected by popular acclaim as Pope. In 1275 Aquinas was ordered to attend a Church gathering and while in route was taken ill at a monastery and died. Some historians argue that he was poisoned by Guelph sympathizers. The speculation was furthered by the fact that the monks immediately boiled away his body an act which could have been perceived to interfere with his Christian resurrection. Among those who held this theory was the ltalian poet Dante whose father and grandfather were both Guelphs.

© San Felese Society of New Jersey

|

As a result of the procession of

knights, soldiers and pilgrims that began to funnel past,

As a result of the procession of

knights, soldiers and pilgrims that began to funnel past,