Two Borders Half a World Apart

By: Tom Frascella February 2017

The Border between Southern Italy and the Papal State:

Although Garibaldi’s August 1862 advance on Rome was stopped by Piedmont troops at Aspromonte it reinforced to the Vatican that its remaining central Italian territory was still a target for the Mazzinian republicans and other Italian “unity” advocates. Throughout 1862 as the Piedmont army increased its presence in the south to 90,000 troops, an uneasy truce existed between Vatican troops and Piedmont troops along the border. This truce was made more difficult in that Bourbon allied insurgents in northern Campania and Basilicata were often forced under pressure to seek refuge in the Papal territory.

The most notable of these Bourbon allied insurgent bands that frequently crossed between borders for safety or raided directly from safe havens in the Papal State was the northern Campanian band of the brothers Cipriano and Giona La Gala. This band was somewhat famous for conducting a raid on a Piedmont prison in northern Campania and freeing its political prisoners. As Piedmont forces increased their presence forced a change in tactics and the La Gala band began raiding from the Papal States. From the winter of 1861 most of the La Gala band were primarily located within the Papal territory. Their presence in the Papal States was of course known and initially encouraged by both the Bourbon Monarchy in exile in Rome and the Vatican. However, the Vatican realized that continued inaction toward thwarting the insurgent safe bases might encourage other insurgents to relocate and serve as an excuse for a Piedmont incursion into the Papal State.

Garibaldi’s ”failed attempt” to attack the Papal States highlighted the Papal States vulnerability to attack. As a result the Pope and the Bourbon government in exile decided to limit the perception of their public support of the insurgency.

In late 1862 the Vatican increased its troop numbers on its southern border which was touted as a measure to limit insurgent crossings, while in fact it was a public relations measure largely intended as a deterrent to potential Piedmont aggression. While formally the Vatican ordered its troops to stop insurgent forces from crossing into the Vatican State under penalty of arrest initially it did little to enforce the order. From the insurgent position the order was of little consequence as it was not aggressively followed and even if it were followed they knew the area well enough to avoid the patrols. From Piedmont’s perspective the additional Papal forces on the border were not perceived as capable of stopping the insurgents or any invasion by their forces should it be ordered. But the Vatican troop presence would make it likely that any crossing of the border by Piedmont would start an armed exchange. Piedmont’s primary concern was that such a move might force Austria and France into action in defense of the Pope and cause France to withhold its secret support for the Piedmont cause.

With the threat of Garibaldi leading an invasion halted as a result of his wounds both the Bourbon King and the Vatican had to determine what their next course of action could/should be toward best preserving their positions. Both thought that restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in the south was an optimal goal for both their interests and security. But both realized that Bourbon support among the people of the south was not strong enough to accomplish attaining the goal of restoration without outside military help.

It was clear that the animosity which developed between Bourbon General Borjes and the insurgents in the south during the 1861 Potenza campaign could not afford to be repeated. That animosity had already resulted in a fracture of support among the insurgents. The Vatican and the Bourbon King realized that a greater fusion of goals and rapport between the insurgents and the Bourbon forces needed to be established if a successful restoration of the monarchy was to be achieved. However, attempting to achieve success by sending in a foreign general who was distrusted and who shared nothing in common with southern Italians had proven not the way to go. Recognizing this it appears that a new plan was developed in consultation with the La Gala brothers, native southern Italian insurgents, in terms of how to achieve greater harmony of forces.

It was determined that Bourbon King Francis might be able to utilize the Spanish forces in exile in France who had been fighting for the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in Spain. This monarchy was closely associated with the monarchy deposed in southern Italy. These exiled forces in France had experience in guerilla tactics from fighting in the mountains of northern Spain. Therefore by temperament, training and experience they could represent an experienced military force loyal to the Bourbon family that could better merge with the insurgents of the south of Italy. Cipriano and Giona La Gala were chosen to go to France along with two additional insurgent companions as emissaries of King Francis. Once there they were to assess the willingness and the ability of the Spanish forces in exile to follow their commands in service to King Francis. Preparations were made by the Vatican and King Francis to smuggle the La Gala brothers out of the Papal States and into France.

I think it is important to note that it was still not entirely clear to the Vatican that Napoleon III was secretly allied to Piedmont. He was publicly professing to defend the sovereignty of the Papal State. As a result the plan was in effect sending the La gala group into hostile territory to recruit from men who were being closely watched by the French Government.

In June/July of 1863 the two brothers and their companions were supplied with fake identities and Vatican passports as part of the clandestine plan. It was then arranged for them to secretly board a French ship for the journey northward. Of course boarding a French ship was in fact placing them in the hands of Napoleon III. Of important legal significance was that once aboard the French vessel they were technically in France and beyond the reach of the Piedmont government and within the jurisdiction of the French. Therefore they should have been safe from Piedmont arrest however not French authority. They set sail for France on a ship named the “Auni”. The ship was scheduled to make port in southern France after a short stopover for supply and cargo in Genoa in July. Genoa was within Piedmont’s territory but legally even when docked in the port of Genoa, as long as they did not leave the ship, they remained on French soil and beyond the reach of the Piedmont authorities. That legal technicality makes what follows very interesting procedural backdrop to what follows and highlights the degree of collusion between Napoleon III and Piedmont King Victor Emmanuel.

But first, before I continue with the story of the La Gala journey I will address what our earliest immigrant ancestors in the U.S. were encountering at about the same time. Some in the face of the continuing build-up of Piedmont forces had already begun to seek refugee status in the U.S.

On the Border between the Union and Confederate States of America 1862-1863:

As I previously wrote, three and possibly several more of our San Felese ancestors who immigrated to the U.S. in 1862 found work with a Trenton masonry contractor. In 1862 this contractor was awarded a wartime contract for work on Union military projects in Washington, D.C. and Maryland. The City of Washington, the Capitol of the U.S. is located on the border between the States of Virginia (Confederate) and Maryland (Union). As such, at the beginning of the war, Washington was exposed as a very reachable prize for the Confederate army especially the Army of Northern Virginia.

During the course of the American Civil War several there were several attempts by the Confederates to capture the city of Washington. As a result large numbers of Union forces were needed on station to protect the Capitol. As the hurriedly organized Union forces massed in and around the Capitol a great deal of supporting infrastructure had to hastily be set up. For example at the beginning of the Civil War there were 12 fortresses and artillery batteries in and around what was then the Union Territory of the Washington/Baltimore corridor. These fortresses had been installed in position for defending Washington from an attack from the East Coast, as the British had done in 1814. During the Civil War however, the danger of attack was from the south. To protect the Capitol from attack from this direction by war’s end an additional 70 fortresses and gun emplacements had to be constructed. Such a rush of emergency military work required substantial labor to accomplish. This work needed to be done at the same time conscription was drawing off many abled-bodied young men. The need for labor provided an opportunity for young immigrants to find work, especially those like our ancestors who did not arrive with English language skills and therefore were not prime targets for conscription for military service.

Enlisters for the Union Army were for most of the war set up right on the docks recruiting mostly English speaking/Irish immigrants as soon as the landed. In addition as more affluent draftees could pay someone to take their place in service this was a way for poor immigrants to obtain several hundred dollars right off the bat. The non-English speaking immigrants were not as sought after as their language deficiencies made them harder to integrate into army units.

Employment on construction projects with materials they were familiar with on the other hand provided our ancestors with an opportunity to work for long stretches with minimum supervision and instruction. If one individual was available with translation skills he could communicate construction orders to a whole crew of workers. This is apparently what their employers did. The method of work crews with one or two translators would become a standard way for employers could take advantage of future non English speaking immigrant labor going forward. This practice was also employed in factories as well as America entered its peak industrial phase. Earlier than this when immigrants were employed they tended to be all English speaking or all of one language base. For example, in Trenton during the American Civil War both the early Cooper-Hewitt Iron Works and the Roebling Wire Mill located next door along the Delaware River provided manufacturing for Union war projects. The Roebling plant that employed approximately seventy people during the war hired primarily German speaking workers as the founder of the company was an 1830’s German immigrant himself.

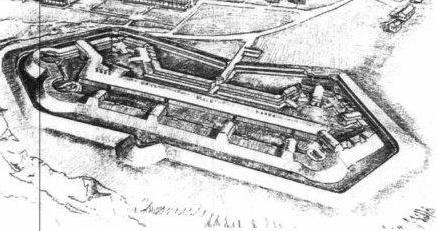

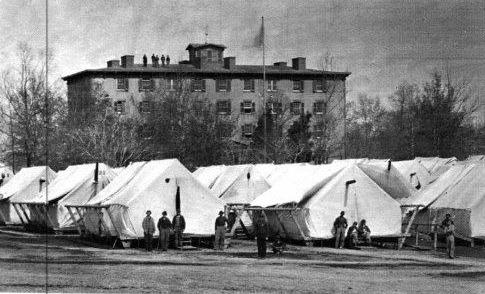

Photograph of the Union fortress Fort Washington an example of a Civil War era fortress

The opportunity for finding work did not mean that the work was easy. Masonry work in the Capitol was backbreaking labor and construction during the ongoing war added additional hardships for those so employed. First, as a result of the magnitude of organizing the war effort and the administration thereof the Capitol city’s population grew to many times its original pre-war size almost overnight. This created a shortages in almost everything including in real housing, basic sanitation and other basic urban services. Tens of thousands of Union soldiers and construction crews converged rapidly in and around Washington and were housed primarily in temporary “tent” like barracks. In fact these accommodations were little more than military and civilian encampments. These encampments had no heat or plumbing, relied on outside latrines, and medical care/sanitation was primitive. In addition the civilian enclaves lacked military structure discipline and policing so at time crime and drunkenness was rampant. In addition, to the above overcrowding issues caused by workers and soldiers arriving, the situation was exacerbated after the Emancipation Proclamation came into effect in January 1863. The City of Washington became a sanctuary city for the many freed slaves, men women and children who once freed, fled to the Capitol to avoid potentially falling back into Confederate hands. Many of the freed former slaves arrived with nothing but the clothes on their backs and little if any marketable skills or education. In short the living conditions were dangerous and difficult.

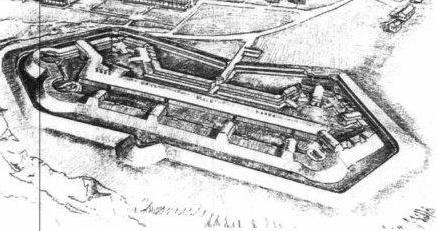

Photograph of Union Army Tent Hospitals and barracks in Washington D.C.

In the summer the above problems created by the sudden influx of people was made worse by the heat. Washington was built on marsh land, a swamp. In the summer in addition to the heat the air becomes quite heavy and trapped. Insect born infections and disease is a content risk. Most affluent city residents, including Presidents and politicians, from the earliest creation of the Capitol sought to leave the city in the summer months to avoid the heat, humidity and often accompanying disease. Even Lincoln primarily stayed outside of the city in the summer. But for workers and soldiers including the thousands of wounded there was no escaping the prevailing conditions and no escaping the risks.

For newly arriving immigrants like some of our ancestors, one interesting “bonus” was working in Washington had the effect of fully immersing them in the American culture of the day. You could say they got a crash course into that American culture at war. That culture was presented to them under circumstances that demonstrated all the good, bad and ugly of a country divided and a city under threat of siege and capture in 1863.

The La Gala Mission on the Border between Italy and France:

I left off the discussion of the La Gala mission with the brothers and their companions boarding a French merchant ship and making port at Genoa before heading for France. As it turns out Piedmont, through its paid informants, spies and/or French government sympathizers were aware of the La Gala mission from the onset. Shortly after the French vessel made port in Genoa Piedmont authorities in the City approached the French consul of Genoa requesting permission to board and arrest the individuals on the French ship. This was an unprecedented request that the French consul nevertheless agreed to. The four men were arrested on board, removed and they placed in a Genoa prison.

When news of this arrest became public it caused an immediate international outcry from the community. First it was a violation of international law even if done with the permission of the local French consul for a passenger on a foreign ship to be removed by authorities from a host port nation. It also appears that there was an 1838 treaty between France and Savoy (Piedmont) which forbade the extradition of those accused of “political activities” from France. Therefore, since the ship was technically French territory the local consul for France had no valid authority. The 1838 international treaty forbade the action taken by Piedmont.

France was required under international law and in order to maintain the appearance of its sovereignty to demand return of the arrested individuals to French control.

This international diplomatic drama was playing out at a time in July 1863 when the Italian Parliament was considering legislation which would essentially codify martial Law as it was being implemented in the south. Based upon reports from Piedmont’s military commanders in the south, martial law was the most effective way to suppress the insurgency. However, there was not legislative or basis for the military action that had been taken as a “temporary” emergency action in response to garibaldi’s campaign. The suspension of due process rights for southern Italians suspected of anti-government activities by the summer of 1863 could no longer be sustained on the Piedmont claim basis of temporary emergency measure. So the political status of the La Gala brothers as southerners and insurgents brought them squarely in the public mind as political activists. For those unfamiliar with this subject the law being considered would eventually become known in Italy as “Legge PICA” after the legislator that proposed the law.

So a very public spotlight was cast on what most people felt were political “insurgents” from the south being turned over to Italian authorities by the French in violation of its own treaties with Italy. Obviously with the world, the French public and the Vatican watching the manner in which the international problem was handled between France and Piedmont required delicate finesse. It became necessary for Napoleon III to become personally involved in defending France’s honor in dealing with the problem. He declared that the French Consul to Genoa had no authority to grant the Italians permission to board the ship and arrest the four individuals. He did this very publicly on July 12th in Paris. He further demanded that the Italians return the arrested individuals to French authorities. That demand was acknowledged by the Piedmont government and was followed by the Piedmont Ambassador to France agreeing with the French Emperor, declaring that the whole matter had been a misunderstanding and of course the prisoners would be returned to French authorities in Genoa.

The honor of France was thus restored and with that accomplished the French officials in Genoa under direction of Napoleon III promptly in a display of good will then turned the prisoners back over to the Italians. As part of an agreement to dampen public outcry over this obvious slight of diplomatic hand King Victor Emmanuel II agreed that the prisoners would not be tried as “political activists” but rather as common criminals and that if convicted and sentenced to death he would commute the sentence of the four arrested to life in prison.

This solution/agreement caused several problems for the Piedmont regime especially in terms of the proposed Legge PICA legislation. Remember that the original cause for the declaration of martial law was the political actions of Garibaldi which was then expanded to the insurgent forces in the south. Piedmont now forced to hold a very public “criminal” trial against those whose actions were in support of the Bourbon regime and inherently “political” in purpose and action. As a result the central legal question became focused on whether the La Gala brothers’ actions and mission was “political or criminal in nature. Obviously the King’s agreement to try them as “criminals” to avoid the ramifications of the French treaty undermined the thrust of the reason for the Legge PICA. The fact that their actions were political was to be expected to be raised in their defense. The prisoners knew that if they could prove “political” cause that the French treaty would force their freedom and would return them to France, an outcome that either Piedmont or France wanted to see occur. At the same time legislation, Legge PICA, was being considered that would make the very same and much less serious actions as those committed by the La Gala brothers a “political act” of rebellion for which summary execution and prison confinement without due process would be allowed throughout southern Italy.

As Piedmont began the preparation for the La Gala Trial the much larger issue of the suppression of civil rights in the south by the proposed Legge PICA legislation became the collateral hotly debated issue. It was this issue then that was the real focus debate in the Parliament of the Italian government and press.

This debate of course assumed that a conviction of the La Gala group after a fair and unbiased trial was a forgone conclusion. After all the King had already agreed to the sentences of the accused. The trial therefore was all about getting the “right” spin for the government and the “right” spin for the accused as criminals which would then allow enough room for the very same acts to still be characterized as political. In turn justifying the passing of the Legge PICA as a necessary act of political suppression to preserve the State.

Back in Basilicata:

The interesting fact was that at the time that the La Gala trial and the extreme measures of the Legge PICA laws were being discussed the insurgency in the south was in fact running out of steam. There was the real possibility that the “rebellion” would have dissipated on its own from lack of financial and popular support. In the mountains of Basilicata during the winter of 1862 and spring of 1863 the insurgent groups loosely associated with Carmine Crocco were content with limiting their actions to small acts against military patrols and or civilians who were deemed as not cooperating with their cause and voluntarily lending the cause material support. As the insurgents pushed the civilian population for support and extracted retribution against civilians they were creating fear but also distrust and anger among those they needed for support.

The more violent need to force support was advancing against a backdrop of the insurgents realizing that they could not go head to head with the ever increasing Piedmont forces. Matters were made worse in that the insurgents in Potenza Province had lost one of their staunchest secret supporters when former Bourbon Prime Minister Giustino Fortunato died of natural causes in the summer of 1862. Without his support, the support of the other former Bourbon elite landowners was unreliable at best. From the insurgency’s outset in Basilicata one of the most aggressive of the Potenza insurgents was Giustino’s Fortunato’s illegitimate nephew Giovanni “Coppa” Fortunato and his younger brother. Many of his early overly aggressive acts were ignored by the insurgent leader Crocco because of his close relationship to the elder statesman. So Coppa held a sort of “protected” status among the insurgents. When Giustino died that status was greatly reduced. Many texts indicate that Giovanni Coppa Fortunato’s insurgent interests and actions centered more on the traditional activities associated with criminality rather than political insurgency. As his actions in the Potenza Province countryside became increasingly violent and directed at civilians his character became questioned in the local communities. As his actions were viewed more as the cruel acts of a violent bandit public opinion and support diminished. This resulted in him becoming despised and alienating himself and his band from support among the locals but more importantly the leadership of the insurgent bands became alarmed at the turn of public opinion toward all of them. As the number of Piedmont troops increased in the area they were able to apply more and more pressure on the locals to not support the insurgents. By the spring of 1863 Giovanni Coppa’s tendencies toward, theft, murder, ransom and assaults on the locals began to become a problem for all of the insurgents which could no longer be tolerated.

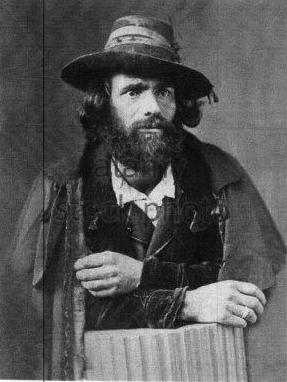

Photograph of Giovanni Coppa Fortunato

The “Coppa” problem appears to have resolved when in 1863 both his younger brother and Giovanni himself were killed. Since the insurgents operated with a high degree of secrecy it is difficult to ascertain how the brothers died. What does seem to be agreed upon was that their deaths were not at the hands of Piedmont troops. It was most often reported that Giovanni was responsible for killing his younger brother. It is said that he did this in a fit of rage because his brother had raided a farm without permission and then failed to cut Giovanni in on his take. Again there is no way to confirm this but the tale seems to focus on the violent nature and disrespect that Giovanni demonstrated to the people around him.

Giovanni’s own death in the spring/summer of 1863 is more interesting in that there appear to be three main versions of how it happened. The Piedmont version arose only after news of his death became generally known among the people. As the Piedmont forces could not claim any encounter were Coppa had been killed they instead began to claim that he must have been wounded in some encounter with the troops and died as a result of his wounds. That version however had no credible incident or encounter that would support the claim and is not considered plausible.

The second version is that Giovanni was killed by the jealous husband of a women he had assaulted or insulted. While given his general violent and abusive behavior such a tale regarding his acts is possible, it also is not likely. Claims of personal vendettas especially involving insults are common as a way of explaining personal attacks upon people of bad or anti-social tendencies. The fact that his men are not reported to have attempted any revenge upon the unnamed person who allegedly killed their leader reduces the likelihood that this version is credible as well.

The third version I find the most interesting. Giovanni Coppa’s insurgent band was made up of mostly fellows from his home town of San Fele. His second in command was Francisco Fasanella. In 1864 about a year after “Coppa” death the insurgency continued to collapse. During that time a number of insurgents began to surrender to Piedmont authorities. Coppa’s second in command who succeed him upon his death himself surrendered to Piedmont troops. It is a clear indication of how badly things were going for the insurgents that so many in 1864 and 1865 choose to surrender. These men because of the passing of Legge PICA knew that upon surrender they faced military like tribunals, not trials. Fasanella following his surrender in 1864 was sentenced to a twenty year prison term. Actually this was in fact a common sentence at the time for Basilicata insurgents.

By the time Fasanella was released in the 1880’s the story of the “briganti” was undergoing an official whitewash in the press as it attempted to largely successfully rewrite Italian history. As part of that attempt a number of now elderly former insurgents were interviewed on the era of “briganti”. Among those was Fasanella. In his interview taken in 1887 he admitted that in fact, he had killed “Coppa” his own band leader. Basically he confirmed that Coppa by his actions against the local population had become too violent and uncontrollable to Crocco and the other bosses of the insurgency. In effect, he was a liability to the cause. As a result, on direct orders from Ninco Nanco, Crocco’s second in command, Fasanella reported in the interview that he had killed Coppa in April 1863. There were no acts of revenge for the assassination as it had been sanctioned by their insurgent leaders.

So it would appear that among the insurgents as early as the summer of 1863 they realized that their position among the people was at risk. Subsequent events would in fact confirm that assessment.

© San Felese Society of New Jersey