The Spring of 1862 in Lucania

By Tom Frascella November 2016

As previously written the insurgent forces in Lucania took decisive and aggressive action in December of 1861 to stock up in preparation for winter in the southern Apennine Mountains. For the most part Piedmont forces although numerically superior were content to hunker down in the mountains’ population centers for the winter. The winter months of that year were harsh and deposited record amounts of snow. The snow further limited movement and communication in the region. Some Piedmont officials optimistically opined that the harsh winter would weaken the insurgent forces. This opinion completely ignored that the bulk of the force were native men fully familiar with life in the rugged mountain passes and terrain. The lack of large scale attacks by the insurgents on the garrisons further led some to conclude that the force had been weakened.

According to Crocco’s writings however his forces rested comfortably during the winter content to recover the wounded and access the forces before them;

“We were in December and we began to slaughter the pigs, that were very fat because they had grazed in the woods where acorn was abundant. The headquarter was mine, as well as 480 people, 40 horses and over 100 dogs of all breeds, large and almost fierce.

From the first days of December 1861 up to May 5, 1862, there was nothing that deserved to be reported, since we were not harassed at all. Cities and small towns by command of the Government made the so-called state of siege, forbidding the people to abandon the country; those who disobeyed were killed. So we spent the winter without being disturbed and it was really lucky, because that year there was such a terrible winter that we could not remember one of similar greatness. So much snow had fallen that we could not walk; it made the newspapers say that the robbers were destroyed and starved while we, as brigands, were healthy and strong as many bulls though without the horns.” “How I became a Bandit” pages 85 and 86.

So clearly the wishful thinking by the Piedmont regime was not echoed by the reality within the insurgent ranks. Still the question of how the insurgents would proceed after the departure, capture and execution of Bourbon’s general Borjes was not clear to any of the competing parties to the conflict.

Inevitably winter came to an end and spring planting in rural Basilicata required that the town folk tend to the fields. For those unfamiliar with rural Basilicata, towns are traditionally to be found on the high ground, built there to offer some degree of advantage if attacked. Farmland is located on the valley floors and grazing land is scattered about. In San Fele for example the town is located near the summit of three converging mountain peaks approximately 2,500 feet above the valley floor. In the 19th century farmers left the town for days and sometimes weeks to tend the fields before returning to the town which presented much too difficult climb to be done daily. In fact a joke frequently repeated by our ancestors as a dismissive response to why they left San Fele was that one day they found themselves at the bottom of the mountain and it was too much trouble to walk back up, so they just continued walking to the port of Naples.

Also it must be appreciated that the majority of the land in locations like San Fele whether mountain, grazing land or farmland was by Italian standards sparsely populated and difficult to keep under view. Again using San Fele as an example, the community had a population of 10,000 people in 1860 spread out during farming season over roughly 40 square miles of territory. The Piedmont garrison stationed in San Fele and elsewhere knew that it would be difficult for them to keep track of the town’s people once they began their farming related activities. Nevertheless they tried through intimidation as they knew many of the locals were insurgent sympathizers if not outright spies. Again Crocco’s writings help get a feel for what was taking place regarding the interaction of Government forces and the populace in the spring of 1862;

“With the end of winter as the lands had to be worked, it was inevitable to allow the farmers to return to their fields; but a lot of strict rules forbade anyone to carry too much bread and food to their place. It was believed that this way the people would have surrendered because of their hunger and no one knew, or rather pretended not to know, that the gentlemen in order to have less harm from us, had given us the rich farms providing that we “eat, drink but do not destroy.” If somebody was reluctant to help us, paid a high price for his refusal and a lot of their wheat fields and their herds of sheeps were destroyed. With the return of the farmers the country regained its normal appearance, and as it had happened in the past, we began gain to receive confidences and information. Among many farmers, there were also spies of the government, but these men were obviously infamous. We met a lot of people, but they were not killed thanks to their profession…” “How I became a Bandit” page 86.

Although there were approximately 60,000-70,000 Piedmont and National Guard troops in southern Italy at the beginning of the spring these were still too spread out and many too poorly trained to as yet constitute much of a threat to the mobile insurgents. They also offered little actual threat for discovering local complicity with the insurgent bands.

The continued employment of guerilla tactics by the insurgents allowed them in the spring of 1862 to resume a string of successful minor skirmishes. They were particularly successful in hitting the small units of Piedmont’s military. With those successes the locals were encouraged to continue their clandestine support of the insurrection. Once again quoting from Crocco’s book at page 87:

“The pursuit of the robbers, especially in Melfi, was at first feeble and weak, due to the deficiency of regular troops, and this encouraged to multiply the horde of brigands. Our small victories in the fighting against the troops, the great moral and the material support received by the reactionaries and the clergy, thrilled us easily, so drunk desirous for blood and ferocity, after unprecedented barbarities, we often considered ourselves as masters of the places and times.”

As with most civil wars the population was probably divided in their support, a third supporting the rebels, a third supporting the government and a third just trying to peacefully survive.

Once it became obvious to the regime that the insurgency had not weakened over the winter the fear that the conflict would escalate into a full blown revolt took hold. The most immediate result of this fear was the decision to continue the anti-insurgent military build-up and suppression of any civilian popular support for it. In terms of bolstering their force 1862 would see Piedmont’s military force in the south grow from around 60,000 in the spring to 90,000 by the fall on 1862. Much of this 1862 buildup continued to depend on a large number of foreign mercenaries as well as northern Italian troops. These troops often served the role of enforcers of military discipline for the local National Guard troops and as enforcers of arbitrary/draconian military laws and summary punishments imposed on civilians.

As the civil conflict continued in the south in the spring the placement of ever increasing numbers of military personnel charged with re-establishing civil order became more and more suppressive toward that civilian population. People were subjected to imprisonment even summary execution based on mere unproven accusation. Military trial and summary punishment had not been a part of the Bourbon regime and so was viewed as a further loss of civil rights. This is of course ironic where the expectation of most Lucanians for a “new” Italy after unification was the hope that they would finally achieve an expansion of civil rights.

The shrinkage of civil rights must have felt like a personal betrayal to many southern Italians, the charter for unification contained the explicit condition that constitutional liberties enacted in Piedmont-Sardinia before the unification would apply in full in the south. Application of due process rights equal to those enjoyed in northern Italy were not only expected, but were constitutionally guaranteed. As those due process rights were suspended or ignored by the military tribunals being established, without civil approval, southern Italians were being reduced to second class citizens.

Another way to consider the impact on Italy of the steady buildup of military personnel in the south should be to view it in the context of the relative infancy of a newly unified Italian nation. At the conclusion of the second War of unification in 1860 Piedmont’s military force numbered about 100,000- 125,000 men. Because the new nation also had its eyes fixed on the acquisition of the Venetian territory a future confrontation with Austria over that territory was likely. The military build-up in the south at this time represented a huge deployment of military assets and expense. In terms of manpower Piedmont was approaching deployment of half of its armed forces for the purpose of suppression of southern unrest. To many in the south and the north it was felt that trying to find a civil resolution to the grievances of the south was the better approach rather than a military solution. In addition it was felt by many that the troops deployed in the south were arguably better deployed in the north in preparation for deployment against Austria. As both the deployment of troops and the size of the Italian army increased in 1862 from 120,000 to 180,000 the deployment in the south began to take on the character of a training ground for that army.

A Small Glimpse into the History of San Felese Insurgence

I have come to realize as I have been writing this history from the comments of many readers that many present day Italian Americans have no idea that Italians and southern Italians in particular have this long history of fighting for the establishment and guarantee of their civil liberties. More importantly they do not know how generations of southern Italians defiantly sacrificed for almost a century against insurmountable odds to try to obtain those rights. Few of our ancestors spoke of it, most preferring to put the past behind them while embracing the freedoms offered in the U.S. Because their efforts in Italy were always from the roll of underdog, the champions of their efforts were largely unheralded and their names secreted and removed from public/historic view. Most of the names of those who struggled in armed resistance were never recorded or were recorded on the rolls of the establishment victors. To the extent that any of the names were recorded in the 19th century those rolls were created to commemorate insurgent defeats. Those surviving testament rolls then represent only a small fraction of the insurgents who participated and only those who were caught, killed or accused and jailed for subversive activities. Those rolls inevitably bear the title of Brigand lists, not lists of freedom fighters. In fact it has only been in the last twenty or thirty years as more revisionist histories have been written that memorials and proper acknowledgements are starting to be created in Italy. Included among those more recent memorials are lists of persons jailed and or executed in some of Naples most infamous political prisons.

I am going to depart from my usual past practice by including a Brigand list that was compiled relating specifically to “brigands from Basilicata. I would like to thank Fred Spero of the Craco society, a sister Lucanian-American group for copying and sending me the compilation. As with most such a lists of briganti those identified were either killed, captured, tried and/or imprisoned. I took the larger Basilicata/Lucanian list and narrowed it to just the San Felese so Identified as Briganti. The lists contain individual narratives with some background concerning the person’s insurgent/ anti-government activities as well as some family info. The list was put authored by Dino (Berardino) D’Angella under the title “Brigantaggio Lucano Dell’Ottocento, Il Dizionario”. The full publication contains hundreds maybe a thousand names of people from many towns in Basilicata who resisted the Bourbon, French or Piedmont regimes as they sought to impose their authority in the south between 1790 and 1865.For their efforts all of those recorded sacrificed greatly and again the names only reflect those who became known to the authorities. For their sacrifice these individuals many of whom simply were trying to obtain rights that we take for granted have been labelled brigands, bandits and outlaws. Sadly instead of being considered freedom fighters the various Italian regimes to this day, have tarnished their sacrifice by calling them common criminals.

I have left the brief history of each person named as it appears in the Italian publication, untranslated. I hope that this does not cause the reader too much difficulty but I wanted to leave the statements about each person in its original form. While I will refer back to this list with comments in upcoming articles I am including it here in its original in order to give some of my fellow San Felese an opportunity to look the list over.

Although I am reserving comments on the list for future articles I would encourage those reading the list to note that there are individual names and biographies associated with “Brigands” who participated in various insurrections going back to 1799. So the list confirms that San Felese participated and sacrificed in insurrections which took place over more than a half century. I would also point out that there are a number of female “briganti” included in the lists. It is my hope that in some small way publication of the list will help San Felese realize that there was a long standing and dedicated history of “freedom” fighting.

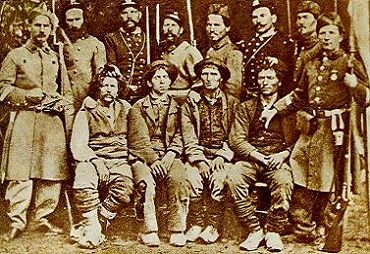

Photograph of southern Italian Insurgents from San Fele, Lucania

List of San Felese Briganti Killed or Captured, Imprisoned between 1799 and 1865

1. Andreucci, Francesco, Contadino. Feceparte forse della banda Crocco. Fu catturato nelle campgne di Accadia in Puglia il 14 Aprile 1863 e passato per le armi.

2. Andriani Francesco. Nato nel 1823 da Antonio. Si dette al brigantaggio aderendo prima alla comitiva di Crocco, alla banda Coppa e dopo alla banda Schiavone.

3. Bagarozzi Francesco, Nato nel 1824 da Ferdinando. Possidente. Appoggio I moti legittimisti nel Melfese nell’ aprile 1861. Fu accusato di favorire il brigantaggio.

4. Bagarozzi Giuseppe, Contadino. Prima appoggio la Repubblica napoletana, poi passo’ alla causa sanfedista. Nel 1804 fu fra I fautori del movimento che si schiero contr l’ introduzione della “decima del lino”, isitituita dal feudatario Doria. Fu coinvolto nei moti antifrancesi e cadde in conflitto nel 1807, ucciso dalla guardia civica di Ruvo del Monte.

5. Brenna Sabastiano, Nato nel 1845 da Vito.nel 1862 si dette al brigantaggio.

6. Cagiano Vito V. Figlio di Pietro Antonio. Contadino. Alias “Spichillo” Si dette al brigantaggio nel 1862. Fu ucciso il 26 giugno 1865 in uno scontro a fuoco con la Guardia nazionale di Baragiano.

7. Cappiello Angela Maria. Detenuta nel 1863 sotto l’accusa di complicita cun la banda Ninco Nanco, fu guidicata dal Tribnale Militare straordinario di Potenza.

8. Caputo Giuseppe Antonio. Popolano. Prese parte al movimento legittimista antifrancese nella primavera del 1806; ricercato si dette al brigantaggio, seguendo prima la banda Giacchetto e poi la banda Vuozzo. Catturato, fu giustiziato nel 1807 a Forenza.

9. CardoneSabastiano. Contadino. Nell aprile 1861 si aggrego alla comitiva di Crocco.

10. Carlucci Giuseppe. Nat oil 1834 da Vito Contadino. Appoggio I moti legittimisti del 1861, indi si aggrego alla banda Coppa. Fu catturato nelle campagne di San Fele nel guigno 1861.

11. Carnevale Angelo. Nato verso il 1810 da Vito. Accusato di Manutengolismo, fu condannato a 20 anni di lavvori forzati, ridotti a 5 anni nel 1867.

12. Carnevale Francesco. Nato nel 1842 da Donato. Contadino. Si uni alla banda Coppa.

13. Carnevale Mauro Antonio. Nat oil 12 settembre 1836 da Bernardino e Blasucci Rosa. Contadino. Nell aprile 1861 prese parte ai moti legittimisti scoppiati nel Melfese. Indi si dette al brigantaggio, seguendo prima la banda Bellettieri, poi la banda Ingiongiolo e quindi la banda Totaro. Si consegno all’Autorita militare in Venosa, unitamente al capo, il 9 febbraio 1865. Processato, fu condannato a 20 anni di lavori forzati.

14. Cavaliere Antonio Nato nel 1836 da Sabastiano. Nel 1861 si dette al brigantaggio, unendosi all banda Coppa. Catturato, fu passato per le armi il 12 Ottobre 1862.

15. Cavallero Antonio Contadino. Si dette al brigantaggio aggregandosi alla banda di Ninco Nanco. Catturato, fu passato per le armi in Avigliano il 12 ottobre 1862.

16. Cirone Giuseppe. Nato nel 1845, da Nicola. Contadino, partecipo ai moti legittimisti scoppiati nel Melfese nell aprile 1861. Successivamente si dette al brigantaggio.

17. Contratano Pasquale.Nato nel 1825 da Benedetto. Proprietario. Aderi ai moti legittimisti scoppiati nell aprile 1861 nel Melfese, aggregandosi alla comitiva di Crocco. Catturato, fu passato per le armi il I Maggio 1861.

18. Coppa Giovanni. Figlio natural di un Fortunato di Rionero. Nat oil 17 gennaio 1836. Alias “Fortunato”. Disertore dell esercito borbonico nel 1860, constitui band propria. Fece parte con la sua banda della comitiva di Crocco e Borjes che nel Novembere del 1861 fece un “raid” in Basilicata, provocando devastazioni e morti.Molto crudele, “sgozzava le sue vittime e ne beveva il sangue”. Le circostanza della sua morte non sono chiare. Forse fu ferito gravemente nell aprile 1862 in unoscontro in agro di Candela in Puglia. Per non cadere nelle mani delle guardie nazionali e dell esercito, si fece soppimere dai compagni. La sua banda, affidata a Michele Volonnino, aias Guerico”, opero con la banda Crocco.

19. Coppa Michelangelo. Nato nel 1835. Popolano, dopo il 1860 si dette al brigantaggio, costituendo Banda proppria. Operon ell agro di Muro Lucano e un po’ nei paesi del salernitano. Catturato in agro di Mur oil 2 aprile 1864, fu passato subito per le armi.

20. Cristiano Guglilmo. Nat oil 14 aprile 1845 da Sebastiano e Stia Teresa. Si aggrego a comitive brigantesche nel 1862.

21. Del Monte Giuseppe. Nato nel 1836 da Domenico. Fratello di Donato M. Contadino, alias “Malacarne” Brigante dal 1862, fece parte della banda Tinna. Si constitui il24 settembre 1863. Fu condannato a 10 anni di lavori forzati. Nel 1867 la pena gli fu ridotta a 5 anni.

22. Delorenzo Francesco. Nat oil 26 dicembre 1847 da Nicola e Mancino Maria Grazia. Fabbro. Si aggrego nell estate del 1864 alla banda Cappuccino, poi alla banda Ingiongiolo, Bellettieri e Coppa. Si constitui il 28 gennaio 1865. Ebbe condanna a sette anni di reclusione.

23. De Marco Pietro. Nat oil 1 maggio 1839 de Bartolomeo e Carnevale Maria. Contadino. Si aggrego a comitive brigantesche.

24. Di Gianni Vito. Nato il 23 novembre 1827 da Giuseppe e Giganti Maria. Mulattiere, analfabeta, alias “Totaro”. Gia soldata borbonico, nell aprile del 1861 prese parte ai moti legittimisti, scoppiati nel melfese. Si dette quindi al brigantaggio, facendo parte della banda Ninco nanco. Era presente allo scontro cruento del 12 gennaio 1863 nel bosco di Lagopesole, conto truppe regolari comandate dal capitano Luigi Capoduro. Per qualche mese si aggrego alla banda Tinna.

25. Il 7 luglio 1863 nel corso di uno scontro a fuoco con le guardie nazionale di Routi riusci a fare prigioniero il comandante della Guardia routese, Saverio Matone. Nell autunno del 1863 constitui banda propria, che in alcuni momento supero anche I 30 uomini. Tale banda fu attiva nell alta valle dell Ofanto e nellalta valle del Bradano. Nel 1864 ebbe non pochi scontri con truppe regolari. In uno di questi conflitti con truppe, comandate dal generale Franzini, la sua banda subi non poche perdite. Alle fine, resosi conto dell inutilita e dell impossibilita de lottare controfotze di gran lunga superiori, ormai inseguito da truppe regolari e da guardie nazionali, si consegno, unitamente ad alcuni suoi gregari, in data 9 febbraio 1865, al generale Pallavicini nella citta di Venosa. Durante il processo, svolto davanti al Tribunale militare di Potenza, ebbe atteggiamento dignitoso, affermando che la sua azione aveva fini politici ma anche era dettata da legittima. Pronuncio almeno un paio di volte la seguente frase: Fummo calpestati e ci vendicammo. Con sentenza del 30 guigno 1865 fu condannato alla pena dei lavori forzati a vita.

26. Di Maio Giuseppe Figlio di Carmine. Contadino. Prese parte ai moti scoppiati nel melfese nel 1861. Sequi Crocco. Fu fucilato nel 1862.

27. Di Marco Francesco. Nato nel 1831 da Bartolomeo. Contadino. Partecipo ai moti legittimisti scoppiati nel melfese nell aprile del 1861. Indi si dette brigantaggio. Fu arrestato nel dicembre dello stesso anno.

28. Dovizio Mariantonia. Detenuta nel 1864 perche accusata di aver favorite dei briganti. Fu processata dal Tribunale militare straordinario di Potenza.

29. Dovizio Vincenzo. Nato nel 1841 da Lorenzo. Fece parte della banda Tinna. Catturato nel dicembre 1863, fu processato nel gennaio del 1864 e condannato a morte, consentenza eseguita il 14 gennaio dello stesso anno.

30. Fasanella Francesco. Nato nel 1830 da Antonio. Alias “Tinna”. Nel 1861 partecipo ai moti legittimisti, con Crocco e Giuseppe Caruso. Indi fu per qualche mese nella banda Coppa. Morto costui organizzo la banda di cui divenne il capo. Spesso opero in collegamento con la banda Caruso. Nel settembre si costitui unitamente a Giuseppe Caruso. Bel 1864 sposo la sua “amante”

Agnese Alanza. Nel 1865 fu condannato a 20 di lavri forazati. Scontata la pena, nel 1885 fu posto in liberta e si uni a sua moglie in San Fele.

31. Faustino Donato M. Nat oil 22 aprile 1844 da Sabastiano. Mulattiere, analfabeta. Nel 1863 si dette al brigantaggio, aggregandosi alla banda Tinna e dopo alla banda Totaro. Si constitui in Rionero il 10 dicembre 1864. Il 30 giugno 1865 il Tribunale Militare di Potenza lo condanno alla pena dei lavori forzati a vita.

32. Fusco Vito Vincenzo. Contadino. Aderi ai moti legittimisti, indi si aggrego alla comitiva di Crocco. Nel settembre 1863 si costituie, ammalato, fu in stato di detenzione nell Ospedale San Carlo di Potenza.

33. Gagliastro Sebastiano. Nato 1’11 marzo 1842 da Gaetano e Papa Caterina. Contadino analfabeta. Dopo il 1860 si schiero a favore dei Borboni. Nella primavera del 1863 si dette al brigantaggio seguendo la banda Mazzariello, attiva nell’alta valle dell”Ofanto. Dopo circa un anno si aggrego alla banda Totaro. Con il capobrigante si costitui il 9 febbraio 1865. Processato a Potenza fu condannato a 20 anni di lavori forzati.

34. Galella Sebastiano. Nato nel 1845 da Vito. Nel 1862 si dette al brigantaggio, aggregandosi alla banda Coppa. Si constitui nel 1863.

35. Giacomo Leonardo. Nato nel 1845 da Pasquale. Contadino. Nel 1862 si aggrego alla banda Caruso.

36. Graziano Livia. Detenuta dopo il 1864 con l’accusa di complicita con I briganti, fu giuudicata dal Tribunale Militare di Potenza.

37. Gruosso Maria. Fu accusata nel 1864 di complicita con I briganti e giudicata dal Tribnale Militare straordinario di Potenza. Ebbe condanna a tre anni di carcere.

38. Iannuzziello Vincenzo. Nato nel 1843 da Antonia. Contadino. Si aggrego a comitivw brigantesche.

39. LaRossa Canio. Nato nel 1837. Contadino. Si aggrego alla banda Coppa. Catturato, fu passato per le armi nel 1863.

40. Maraffino Berardino. Figlio di Sebastiano; nato nel 1841. Contadino analfabeta. Nell Agosto 1863 si dette al brigantggio, facendo parte della banda Mazzariello quindi si aggrego alla banda Coppa, poi a quella di Tinna ed infine alla banda Totaro. Il 2 dicembre 1864 si constitui. Fu condannato a 15 anni di lavori forzati.

41. Maraffino Maria Antonietta. Nata nel 1842. Contadina. Fece parte della banda Coppa nell’aprile 1861. Secondo il Di Cugno sarebbe stata fucilata il 16 giugno 1862.

42. Mare Donato. Nato verso il 1818 da Vito. Accusato di complicita con I briganti, fu condannato a 20 anni di lavori forzati, pena ridotta nel dicembre 1867 a 10 anni.

43. Mare Pasquale. Sacerdote. Appoggio le truppe del cardinal Ruffo nel 1799, Nel 1801 avrebbe favorite la costittuzione della banda di Michelangelo Natale, di cui fu –secondo Pedio- l’ispiratore e la mente organizzativa.

44. Marinaro Vito. Figlio di Nicola; nato nel 1841. Gia condannato per reati comuni sotto I Borboni, aderi al brigantaggio prima con la comitiva Coppa e poi con la banda Tinna. Constituitosi il 14 Settembre 1863, fu condannato a 15 anni di lavori forzati.

45. Martinelli Beatrice. Nato nel 1838. Contadina. Partecipo ai moti legittimisti nel melfese nel 1861, aggregate alla banda Coppa. “Proietta, maritata, druda di briganti”, Secondo Varuolo fu catturata nel giugno 1861. Il Di Cugno la vuole catturata dal 33 Rgt Bersaglieri e passata per le armi il 16 giugno 1862.

46 .Massari Antonio. Nato nel 1841 da Pietrantonio e Gaudioso Elisabetta. Proprietario, acculturate. Aderi alla banda di Crocco e poi a quella di Totaro. Si constitui il 17 settembre 1863. Processato a Potenza, fu condannato a 10 anni di reclusione.

47 Muccio Donato. Nato nel 1840 da Sebastiano e De Giacomo Elisabetta. Contadino. Aderi a comitive brigantesche. Fu catturato il 5 aprile 1864. Processato, ebbe condanna ai lavori forzati a vita.

48 Murena Mauro. Popolano. Partecipo ai moti antifrancesi nel 1806. Indi, per evitare di essere catturato si dette al brigantaggio. Fu ucciso in uno scontro a fuoco nell’ agostyo 1809 in agro di San Fele.

49 Natale Michelangelo. Contadino. Alias “re di lagopesole”. Nel 1799 evase dal carcere dove scontava una pena per reati comuni. Recatosi nel suo paese, constitui banda armata della quale fecero parte molte persone ricercate per I fatti del 1799. Occupo il castello di Lagopesole, che transform per due tre mesi in un vero quartiere generale. La sua comitiva fu molto attiva nel Vulture e nell alta valle dell Ofanto. Mise a ferro e fuoco San Fele il 14 gennaio 1801 e nel marzo di quest anno. Fu catturato nel 1802 e passato subito per la armi.

50 Nigra Franco. Nato verso il 1837. Soldato borbonico abandata. Appoggio Crocco. Fu catturato nel dicembere 1861 in agro di San Fele.

51 Nigro Frabcesco. Nato nel 1838. Soldato borbonico sbandato. Si aggrego a comitive brigantesche. Fu arrestato nel giugno 1861.

52 Nigro Vincenzo. Nato nel 1844 da Potito e De Giacomo Maria. Alias “Senzascarpe”. Fece parte della banda Totaro.

53 Padula Antonio. Nato nel 1833 da Domenico. Si dette al brigantaggio dopo il 1863. Arrestato il 12 luglio 1865, venne condannato a 15 anni di lavori forzati.

54 Pizzirusso Giovanni. Nto nel 1833 da Carlo. Contadino. Si aggrego alla banda Coppa. Fu ucciso in uno scontro a fuoco.

55 Remollino Michele. Nat oil 28 giugno 1835 da Domenico. Contadino. Alias “Tappone”. Nel giugno 1860 diserto dall esercito borbonico. Nell Agosto 1860 si dette al brigantaggio, facendo prte prima della banda Ninco Nanco, poi di quella di Coppa e poi di Totaro. Si constitui in San Fele il 24 Marzo 1865. Il 30 giugno dello stesso anno il Tribunale di Potenza lo condanno ai lavori forzati a vita.

56 Ricigliano Felice. Nato nel 1839 da Michele. Zappatore. Nel 1862 si dette al brigantaggio, aggregandosi alla banda Tinna. Ferito, fu arrestato il 19 febbraio 1864. Condannato ai lavori forzati a vita; nel 1887 la pena gli fu ridotta a 30 anni.

57 Rubino Donato Nato nl 22 gennaio 1840. Da Antonio e Giallella Francesc. Contadino. Alias “Passatossa”. Si uni nel 1862 alla banda Coppa.

58 Ruggieri Donato. Nato nel 1843. Contadino. Alias Fuscillo”. Si aggrego nel 1861 a comitiva brigantesca.

59 Santoro Rocco. Nato nel 1833 da Antonio. Nel 1862 si aggrego alla banda Coppa. Dopo pochi mesi si constitui.

60 Setteducati Antonio. Nato verso il 1835. Soldato borbonico sbandato. Si aggrego alla banda Crocco nella primavera del 1861. Fu catturrato il 1 decimbre 1861 in agro di San fele.

61 Silvestri Antonio. Contadino. Prese parte ai moti legittimisti scoppiati nel melfese nell aprile del 1861. Nell estate dello stesso anno si dette al brigantaggio.

62 Tatangelo Carmine. Contadino. Partecipo ai moti legittimisti nell aprile 1861, indi si aggrego alla comitiva di Crocco. Forse si contitui nel settembre 1863. Alla fine di questo mese era., in stato di detenzione, ricoverato presso l’Ospedale San Carlo di Potenza.

63 Tomasulo Michele. Nato nel 1845 da Sebastiano e Tuzzieri Rosa. Contadino, alias “Pezzente”. Nel 1862 si aggrego alla banda Totaro. Si constitui in San Fele l 18 aprile 1864. Fu condannato a 15 anni di lavori forzati.

64 Tomasulo Pasquale Nato nel 1838 da Vito e Carnevale Rosa. Contadino. Si aggrego a comitive brigantesche nel 1861.

65 Tomasulo Pietro. Nato da Giyseppe e Bagarozza Angela Maria l 8 settembre 1841. Si agrego alla banda Coppa. Fu tratto in arresto il16 febbraio 1862 e passato subito per le armei.

66 Trunnolone Sebastiano. Figlio di Francesco. Partecipo ai moti legittimisti nell aprile del 1861. Indi, si aggrego alla banda Crocco.

67 Tifaro Sebastiano. Figlio di Vito. Si dette al brigantaggio aggregandosi alla banda Coppa. Mori in conflitto forse nel 1863.

68 Vitella Domenico. Nato nel 1844 da Vito Michele. Patore. Appoggio bande brigantesche. Ricerato, si costitui e fu e fu condannato a 20 anni di lavori forzati.

It is worth pointing out the length of sentence that Piedmont tribunals dished out post 1863, often averaged 10 years to life. The punishments reflect the serious manner in which the briganti threat was treated. It also represents the degree of risk, sacrifice and commitment that these San Felese were willing to endure for freedom. Also of note is that some of the post 1863 entries were for crimes described as supporting, being complicit or being sympathetic to insurgents. This list may also begin to give the reader some understanding as to why so many San Felese started coming to the U.S. as early as 1862 thru the mid-1860’s.

One comment I should make is that this is at best a very partial list. I suspect from everything that I have read that if insurgent participation in the various uprisings from the 1790’s thru the 1860’s had been accurately kept San Felese killed or jailed would be 2 to 3 times the figure reported here. Until about 1862 there was no organized effort to identify insurgents and those killed in the field often were just left to rot or displayed for propaganda, as in the case of the photo below.

Photo of four insurgents captured and executed by Piedmont soldiers, the men sitting are dead.

San Felese active participation in support of various uprisings during seventy years of insurrection is extensive. Actual numbers since most were not caught or identified was probably ten times the figure on this list. Civilians in the town sympathetic to the cause but not active in the revolts again may be on the order of several thousand from the town of San Fele alone. San Fele had a long history of encouraging and supporting the struggle for Civil Rights. One of the under-appreciated aspects of this is that that intent in acquiring and insuring those same rights when they immigrated to the U.S. did not stop. A separate and I would say remarkable story is how the earliest of the San Felese immigrants when confronted by prejudice and discrimination organized their communities to deal with it and other issues impacting them here. Our own organization was founded as a later successor organization to the earliest attempts at securing the liberties, securities and benefits of a society that was at times hostile to their presence.

© San Felese Society of New Jersey