The Arrival of the Piedmont Army in the South

By: Tom Frascella December 2015

Although the arrival of the Piedmont army was anticipated and even desired by the insurgent forces throughout the south, there nevertheless was some question prior to the plebiscite as to how they should be greeted by local forces. After all, the local forces regarded themselves as militia supporting their regional provisional governments under the command of Garibaldi, the Dictator. While many of the insurgents favored unification or one nation of Italy the regions of the south were at this juncture acting more as a loose confederation of States, much like early colonial America during the revolution.

As early as September 23rd insurgent commanders in Abruzzi had requested orders from Garibaldi as to how the Piedmont regulars were to be greeted when they crossed the frontier. Garibaldi, was not at his Neapolitan headquarters when the request arrived and his secretary Bertani responded in his stead with the following instruction; “If the Piedmontese wish to enter, say to them that before you permit it you must ask instructions from the Dictator”. (Garibaldi and the Making of Italy) page 226. This response was entirely consistent with the way in which most of the southern insurgents saw their status within their regional network. While they may have supported the entry of Piedmont forces it was in their minds as invited allies not as overlords. The September date of the request is also an indication that the insurgents in the south expected the arrival of Piedmont forces would occur sooner rather than later and would occur in the Abruzzi as opposed to northern Campania.

However, despite the initial response, one that was consistent with the local insurgents perception of their status, on the following day when Bertani informed Garibaldi of the request and response Garibaldi did not approve of the order. He reissued the order to the insurgent commander in Abruzzi with the following message; “If the Piedmontese enter our territory, receive them like brothers”, (Garibaldi and the making of Italy) page226. This was an order that failed to provide much in the way of clarity to the poor local commander and probably reflects the general state of political uncertainty that was present. It is however significant in that while retaining the title of Dictator he was already withdrawing from any suggestion of his personal command over the forces coming into the south from Piedmont.

King Victor Emmanuel II joined his forces at Ancona on the east coast of the Papal States on October 3rd. From there together with his army of roughly 35,000 men the King began his march toward the northern border of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies six days later on October 9th. He and his army reached the town of Grottammare, the southernmost town in the Papal territory by October 11th. From here he was only a short distance from the border with Abruzzi where it is clear from the earlier correspondence he was expected to cross. At Grottammare the King delayed his army from moving southward and crossing the border until he received word that the plebiscite had been arranged. That confirmation was delivered on October 15th at which time he was told by messengers from Naples that the Plebiscite would be held on October 21st. The King, without waiting for the plebiscite to actually be held then restarted his southward march crossing into the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies by traversing the Tronto River into Abruzzi.

At the time of the king’s crossing the Abruzzi region had already declared its independence from the Bourbon regime and set up its own provisional government under the direction of Garibaldi as Dictator. So as the King’s army began its march through the territory it was greeted warmly by Abruzzi’s population.

The principle problem for the King’s army was that in traversing Abruzzi, from east to west, toward Naples the mountainous terrain was challenging to an army which brought with it many cannon and siege weapons. Like many areas in the southern Apennines of this time the roads and bridges were badly neglected. This slowed the army’s progress south.

Within a few days of entering Abruzzi it was decided to send a vanguard force forward that was less encumbered and could move faster through the mountains. That force was placed under the command of General Cialdini. General Cialdini was a competent, experienced and aggressive military commander. As he proceeded ahead of the main body of the Piedmont army he was first to reach the region which bordered northern Campania. As previously written western Abruzzi and northern Campania were equally divided politically between insurgent and pro-Bourbon citizens.

General Cialdini began to receive reports of pro-Bourbon actions inflicted on insurgent forces in the region. To describe the situation and reports the General received I shall refer to the reports as cited in (Garibaldi and the Making of Italy) page 268.

“After they had passed Sulmona, the political sympathies of the inhabitants were less unanimous. There was still an enthusiastic “Italian” party to welcome them, but at every turn of the road they saw fresh evidence of civil war and massacre. The “good Italians” came in with stories, usually only too true, of massacre and mutilation which their relations and friends had suffered. Rough justice was administered on the roadside by Piedmontese court-martials assisted by firing parties, and a proclamation was issued that all peasants found with arms in their hands would be shot”.

The above quote might suggest to the reader that the military trials and executions of civilians was a necessary function of the vanguard’s progress forward. However earlier in the book cited, which by the way is pro-unification in its tone and therefore often is not critical of the unification forces action, there is an unfavourable comparison of these executions when compared to the earlier acts of Turr in putting down August civil riots in Sicily. At page 188;

“Turr acted not only with vigor but with clemency. He shot two of the ringleaders of the peasant massacre, though local Liberals who had suffered begged him to shoot a round dozen, and disliked the practical application of his doctrine that a new era of liberty and brotherhood had dawned for all Italians. The repression of similar reactionary massacres in Molise and the Abruzzi, as conducted by General Cialdini and the Piedmontese regulars in the later months of the year, was on a scale of vengeneance more calculated to satisfy the local demand than anything that Garibaldi or his lieutenants were ever known to permit”.

It should be noted that General Cialdini’s summary orders of execution and proclamation regarding the bearing of arms were issued by military edict against civilian non-combatants. Further his authority to issue such orders against civilian inhabitants has no precedent and was not granted by the insurgent forces or local government authorization.

As far as I can discern Garibaldi, the Dictator, also had certainly not authorized the acts, or was even aware that they were taking place. In addition, the Abruzzi provisional State government had not issued such authority to General Cialdini. I can only assume that Cialdini considered that he had such authority vested through King Victor Emmanuel II. I suppose that his authority in fact was confirmed in that there were no recriminations for the acts from the King. The Piedmont forces were acting at this early juncture as if they were the authority, under martial law, with no need for local authority’s approval.

I think it is important to note that this dispensing of extreme military justice upon civilian subjects is a clear demonstration of martial law with no hint of civil due process. Further, It is important to note that no effort was made to arrest, detain or to turn over to civil authority any of the alleged pro-Bourbon civilians considered in violation of the military proclamation. The only punishment for suspected pro-Bourbon resistance was summary execution.

General Cialdini and his vanguard quickly reached the area near the Gaeta front. By October 20th 1860, the day before the scheduled date for the plebiscite vote for annexation in the Kingdom of the Two Siciliies the vanguard had crossed into northern Campania. The rapid movement of the force probably allowed the natural controversy that should have followed the summary executions not to arouse public condemnation before the plebiscite vote.

As Cialdini’s forces arrived in northern Campania they encamped near the town of Isernia where three days before a small Garibaldian force had been driven back by a much larger force of Bourbon loyalists. Cialdini’s force was a full two days ahead of the main body of the Piedmont army. The loyalists in the town had been supplemented with aid from Bourbon regular troops. By October 20th approximately 5,000 Bourbon regulars under the command of General Scotti, were holding the town of Isernia.

In what was probably a precursor of how the military campaign would proceed after the arrival of the Piedmont forces in the south, General Cialdini did not asked for support from the insurgent forces either as he traversed Abruzzi or upon reaching Isernia. Upon his arrival at Isernia no effort to communicate or enlist the help or support of the Garibaldian forces in the area was made. As will become obvious Cialdini held southerners and their military prowess in contempt. His general sense of contempt was not diminished by the engagement which was soon to follow his arrival.

Shortly after the arrival of General Cialdini’s advanced Piedmont guard, General Scotti in a rare display of aggressive military action ordered his 5,000 Bourbon troops out of Isernia and to engage the smaller Piedmontese force. This might have been effective if General Scotti had been even modestly competent. Unfortunately for his Bourbon troops he was not. As he marched his men out of Isernia toward Cialdini’s forces he sent out neither scouts or advanced units. Instead he choose to march his men in perfect formation into the defensive positions hastily set up by Cialdini. The result was another disastrous rout for the Bourbon forces. Cialdini’s forces ambushed and quickly charged the defenseless and exposed Bourbons. In a very short time the Bourbon force was reduced by 1,000 men killed, wounded or captured, including the capture of General Scotti. The remaining 4,000 Bourbon survivors broke rank and retreated to Bourbon lines closer to Gaeta. From his position at the now captured Isernia General Cialdini waited for the arrival of King Victor Emmanuel II and the main body of his Piedmont army.

On October 25th four days after the Plebiscite and five days after the engagement at Isernia , Garibaldi returned to the front lines near Capua. Garibaldi with several Garibaldian regiments made an uncontested crossing of the Volturno River near Cajazzo. The Bourbon forces had pulled further back to positions near Capua and therefore part of the north bank of the Volturno was no longer contested ground. By crossing the river it put Garibaldi’s forces in position to link up with King Victor Emmanuel’s forces moving southward. From the north side of the Volturno River Garibaldi’s forces advanced without resistance northward and on the evening made camp near the hills of Cajanello and Vajrano.

There Garibaldi awaited the arrival of King Victor Emmanuel II and his army which had reunited with Cialdini’s vanguard and was itself encamped nearby a few miles still further to the north. After setting up his own camp Garibaldi sent as representatives Missori and Zasio to inform the King of his position and to offer him welcome and homage. Again, the psychological/propaganda aspect of the moment was clearly recognized by Garibaldi and the Piedmont regime and therefore carefully controlled and organized. Garibaldi could easily have marched his regiments up to the King’s encampment and presented himself as victor and liberator of the south. He did not. Instead he announced his position and waited dutifully for the King and his army to come to him with King Victor Emmanuel playing the role of the conquering monarch from the north.

On the morning of October 26th after Missori and Zasio returned from meeting with the King, Garibaldi and his senior staff broke camp and travelled a short distance on the road that the Piedmont army would be using on their advance southward. Again, I note that he left his army behind. It was obvious that his intent and possibly his orders were to greet the King without the presence and status of commander of the southern insurgent army. Garibaldi halted his travel at a small tavern, (Taverna la catena) along the road and there he waited for the arrival of the King and his army.

Eventually as thousands of Piedmontese regular troops passed his location Garibaldi heard the music of the King’s band and mounted his horse, riding to the sound of the music. When the two men met, Garibaldi greeted the King with the words, “Saluti il primo Re d’Italia”, (I hail the first King of Italy). It is in the dynamics of the meeting that we see the first hints of how the annexation of the south was about to take place. Clearly absent were the people of the south who had fought to make this moment happen.

More importantly there was no “joining” of the military force. This was the King’s show, and joinder with the southern insurgents was treated as unimportant, with the disdain of an unnecessary appendage to the solemnity of the moment.

Picture of Garibaldi greeting King Victor Emmanuel II

Despite what some historians have referred to as “the warmest of greetings” it was at this meeting that we are lead to believe that the King told Garibaldi that the Piedmont army would assume the full conduct of the campaign going forward. However, from the dynamics of the meeting, including that he had left his regiments behind, I believe that Garibaldi had already signed off on this. Garibaldi left the meeting with his staff, travelling back to his regiments by way of secondary roads, and not as part of the advancing Piedmontese force. Once back at his encampment he gave orders to break camp and he and his troops retreated back across, and south, of the Volturno River. The enemy forces that had been nearby upon witnessing the arrival of the Piedmontese force further retreated that day to defensive positions behind the line at Gaeta.

On October 27th , the next day, King Victor Emmanuel II made his only gesture of recognition of the Garibaldian forces entrenched in defensive positions south of the Volturno. He travelled, accompanied by a small guard and crossed the Volturno. There he briefly visited the Garibaldian troops at Sant Angelo. Garibaldi was notably not present at the location at the time of the King’s visit. Historians suggest that he had not been informed of the King’s intent to visit. However, again based on dynamics I believe he was intentionally absent in order to give the King the lead without the distraction of Garibaldi’s presence before his men. It was left to Garibaldi’s commander at Sant Angel General Medici together with Nino Bixio’s lieutenants to greet the King on his “surprise” visit. The Garibaldian forces unaware in the shift of command greeted the King enthusiastically. All suggestion that the southern troops were to be dismissed and the Piedmont forces were to take charge was carefully hidden from the men of the south.

Later on the 27th the King upon his arrival back at his headquarters divided his forces then encamped at Teano. In effect launching his direct assault on the Bourbon forces entrenched in northern Campania. Half of his force was sent to confront the Bourbon forces defending the line at Garigliano and Gaeta and the other half, under the command of General Della Rocca was sent south to confront the Bourbons at Capua. All of Garibaldi’s insurgent force arrayed against the Bourbons were dug in at Capua and south. So it fell to General Della Rocca to negotiate the delicate transfer of front line command between Capua and Naples. Garibaldi was well aware that his command of the forces and their role as front line soldiers had been eliminated in the plans going forward by the Piedmont military high command. Garibaldi himself became an active participant in the transfer of roles while hiding the situation and intent of transfer from his men;

“Although the redshirts were no longer to be allowed to take part in the serious operations of the campaign, yet on October 28 their services were still required for yet a few days longer to help guard the lines for the royal siege batteries. Garibaldi, fearing that his men might be annoyed at receiving orders from Della Rocca if they considered that a slight was being put upon themselves or their chief, not only placed the whole of his army at the absolute disposal of the Piedmontese general, but was at pains to devise a plan whereby Della Rocca’s orders were conveyed to the redshirts through Sirtori, as though they still came from Garibaldi himself. He strictly enjoined on his staff to prevent the men from knowing that the orders did not in reality emanate from him”. (Garibaldi and the Making of Italy), page 274.

With regard to how Garibaldi felt at the sudden shift in power and his ouster of command I can only assume he accepted his fate as part of the greater struggle for unification. Further I believe that the transfer and his role in the transfer of power had been understood, discussed and planned for months prior to its happening. In his autobiography “My Life” page 125 he does express some limited disappointment in the following lines;

“In an attempt to improve my fellow soldiers’ circumstances I asked for the Army of the South to be incorporated into the national forces; this request was unjustly refused. The fruits of the conquest were welcome, but the conquerors were not.”

However, there is no indication of resentment on his part or objection.

Following General Della Rocca’s arrival at the southern front Garibaldi further physically removed himself from the front and his men. He removed himself to his headquarters in Caserta. General Della Rocca immediately began placement of his siege cannon for an assault on Capua. By November 1, 1860 Della Rocca’s preparation were complete and he began his bombardment of Capua at four in the afternoon. An intense artillery exchange between the opposing forces continued throughout the day and most of the night. At morning light it was revealed that the PIedmontese bombardment had done severe damage to the civilian centers of Capua. In light of this and at the urging of the civilian population of the town the Bourbon commander surrendered the position in order to avoid further civilian deaths. On November 2, 1860 the Bourbon commander surrendered Capua and he and 11,000 Bourbon soldiers became prisoners of the Piedmontese. This substantial surrender of troops reduced the Bourbon forces from 45,000 to 34,000 now situated at the Garigliano line and the formable fortress at Gaeta where Bourbon King Francis was headquartered.

In essence Bourbon King Francis was encircled and the Piedmont siege of the fortress should have resulted in a quick capitulation of the position. Especially in light of the fact the encirclement included the placement of the Piedmont fleet on the seaward side of the fortress. However, the siege did not progress quickly for an interesting reason. Napoleon III ordered his fleet in the area to prevent the bombardment of the fortress by the Piedmont navy. It may be that because the Bourbon Queen was a member of the Austrian royal family that he did not want to provoke the Austrians from entering the war in order to effectuate a rescue. At any rate the bombardment commenced only from the land side which was much less effective in causing damage to the position. The land bombardment commenced on November 12th exclusively from the land side. The rather ineffective bombardment from the landside continued rest of November through January of 1861.

Picture of the Siege at Capua

At about the same time King Victor Emmanuel’s northern force began to actively engage the Bourbon forces at Garigliano. On October 31st Piedmont naval forces began a bombardment of the Bourbon forces entrenched along the Garigliano line several miles south of the Gaeta. The bombardment from the sea to their rear and the enemy lines at their front forced the Bourbon forces to retreat ever closer to the Gaeta fortress. In essence the Piedmont army was tightening the noose around the Bourbon stronghold. On November 2 the same day that Capua fell the Piedmont army conducted a successful action against the Bourbons at Mola di Gaeta. With the taking of that position the Piedmont army was in position to begin bombardment of the fortress by land. Over the course of the next ten days the Piedmont command brought up its naval forces in preparation for naval bombardment as well as land based bombardment of the Bourbon position. During that time some 17,000 Bourbon troops successful broke out of the surrounded position and escaped northward to the safety of what remained of the Papal State territory. This further reduced the Bourbon force to approximately 18,000 men surrounded by overwhelming Piedmont fire power. The siege of Gaeta had begun.

Of important historical note is that while Garibaldi was surrendering his command in the south to King Victor Emmanuel in October/November 1860 an important American event was happening across the Atlantic Ocean, in the United States. The Presidential election of 1860 was coming to a climax. For several decades the U.S. had endured rising political pressures regarding the issues of States Rights versus Federal Supremacy and on the issue of Slavery. As to Slavery the question was both an issue of continuation vs. abolishment and restriction of the institution of slavery to existing “slave” States vs. expansion of slavery into new organizing U.S. territories. The elections of 1860 brought these hotly contested issues to the forefront. Not surprising is that there was great division among the people as to the proper way to address the issues or to find political solution. That division of public opinion can be seen in the fact that there were ultimately six major national party factions organized with each offering both a political position and a candidate for President.

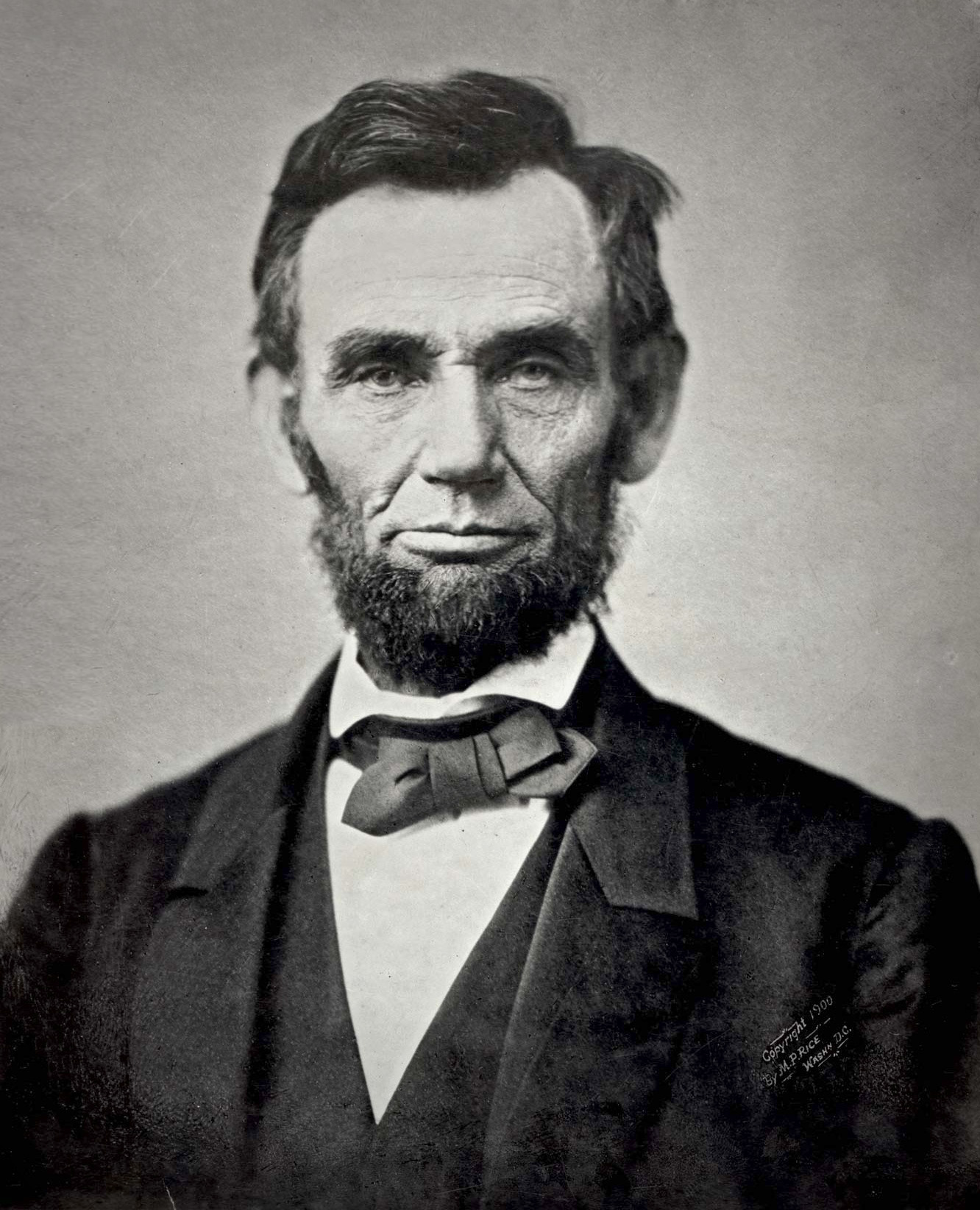

Ultimately as any school child knows Abraham Lincoln was elected President.

Picture Abraham Lincoln

Probably less known was that based upon the number of candidates and positions, Lincoln won with only 40% of the popular vote, although the States that he won provided the required electoral college majority necessary for the Presidency. This of course means that 60% of the Americans eligible to vote in the election did not vote for Lincoln. Voting turnout among registered voter, unlike today, was very high in the 1860 election. In fact, at almost 82% it was the highest that had ever been recorded in the U.S. up until that time. Only the election of 1876 garnered a higher percentage of registered voter, and only by half a percentage point since that time. Obviously the country was well aware of the significance of the vote that year and participated fully.

I have consistently tried to point out that from a Lucanian/Southern Italian perspective mass immigration to the U.S. should be tracked from the 1850’s. While initial numbers were admittedly small those first Italian emigres were impacted by the American political climate and would be effected by the course of the American Civil War. My intention therefore is to spend some small amount of time over the course of the next three articles discussing the implications and impacts of the American political climate on those immigrants.