The Siege of Gaeta

By: Tom Frascella April 2016

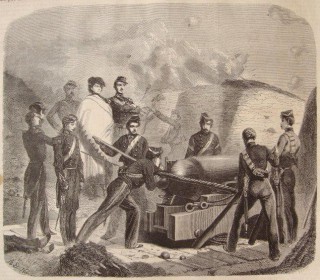

Photograph of Fortress at Gaeta Italy

At this point I will resume taking up the topic of what is generally considered, in some histories, as the conclusion of the military campaign associated with the Second War of Italian Unification. Our last article on the subject of this conflict left off at the point in the conflict of mid-November 1860. At the end of October King Victor Emmanuel had successfully lead his men into position in northern Campania.

With the help of Garibaldi’s insurgent forces, Victor Emmanuel had boxed in King Francis’ forces on the coast at Gaeta and Capua. By November the Bourbon forces had dwindled to about 30,000 men. In early November, the siege of Capua concluded with a victory for the Piedmont forces however 12,000-15,000 Bourbon Troops successfully escaped to the Papal territories. This left the Bourbon forces including King Francis and his wife encircled at Gaeta.

In all Bourbon King Francis then had about 12,000-15,000 men remaining under his immediate command and faced a force of about 35,000 Piedmont regulars supported by about 30,000 insurgents with Garibaldi. King Victor Emmanuel tightened the lock on Gaeta with his land forces and moved his naval fleet into position. At this point the Bourbons were outnumbered and surrounded by forces both land and sea. The Piedmont army was then in position to make short work of what should be the concluding major military operation of the southern unification campaign.

It was however at this point that the direction of this battle and the politics, both international and national intersected. That interplay caused the progress of the battle to be a prolonged rather than a massive overwhelming bombardment. What was to be the inevitable military victory, a victory placed at the feet of King Victor Emmanuel by Garibaldi’s brilliant actions, therefore had to wait.

International politics surfaced at Gaeta and things took an unexpected turn. The French fleet suddenly appeared off the shoreline of Gaeta and placed itself between the Piedmont navy and its effective range for a naval assault on the fortress. Unwilling to risk direct confrontation with the French navy Victor Emmanuel ordered his fleet to stand back. This meant he could only mount a land based artillery assault on the fortress and that from only a single artillery assault point.

Realizing that the Bourbon forces were trapped and had little possibility of escaping on their own King Victor Emmanuel settled in for a siege of the fortress rather than a massed army assault. Such a land based assault could not be supported fully by artillery without the naval force in proper position.

At the time King Victor Emmanuel and his advisors prepared to attempt a diplomatic solution to the French naval intervention rather than having his naval forces confront the French navy. It is known that the King’s advisors including Cavour were in direct contact with napoleon.

On the more domestic front King Victor Emmanuel also realized that there were considerable issues that had to be addressed within his newly acquired southern Kingdom. These issues could not wait out a long siege without being addressed. With the siege apparatus in place the King was free to make some immediate decisions regarding the consolidation of his power and authority in the south.

History suggests that the King was counselled by two opposing primary sources, the Garibaldi/Mazzinian faction and the Cavour/Piedmont Military faction. Both were said to be advocating on how to move forward on the unification of the north and south. Both factions are said to have also been advocating for how best to conclude the military end of the war. It is difficult to determine how flexible King Victor was at that point versus having already decided on a plan of action. It is also unclear how much counsel or how much influence Garibaldi had with the King in the process. It is not even clear what Garibaldi’s advocacy on the issues was. For sure Mazzini was distrusted and in disfavor with the Piedmont regime. Also Mazzini was clearly in support on invading the Papal States and probably establishing a democratic Republic.

First historically in terms of Garibaldi’s advice to the King it is generally held that Garibaldi had lobbied the King that he, Garibaldi remain as Dictator for a year in the south serving under the direct supervision of the King. It is also suggested from historical texts that Garibaldi advised the King that the King’s personal administrative presence, for at least a year, was required in the south. Garibaldi felt this was critical to a smooth transition into a unified country and the development of a loyalty with the people of the south to the personality of King Victor Emmanuel. Whatever the King planned, it is clear from his actions that he had no intention of Garibaldi remaining in southern Italy as dictator or remaining in southern Italy himself after the conclusion of hostilities.

History also suggests that Garibaldi lobbied for his forces, which had won the lions’ share of southern territory, be fully absorbed into the regular Piedmont army. This would include the approximately 30,000 he had with him at Caserta in the field and another 10,000 or so, serving as security/national guard throughout the south.

Both requests were denied. Instead, Garibaldi’s forces were disbanded and sent home with a small stipend for their efforts. Only about 5,000 of Garibaldi’s troops, mostly foreign national troops Hungarians, were absorbed into the Piedmont force in the field at first. Of the remaining roughly 35,000 men associated with Garibaldi’s campaign, approximately 10,000 who had come from northern Italy, were returned home. The remaining southern insurgents returned to their villages without reference or indication from the regime as to the promises Garibaldi had made for pardons, commissions and enlistment. Whether the promises to the insurgents would be kept by King Victor Emmanuel was at the time of disbanding, politically and intentionally kept unclear.

Once the King had achieved Garibaldi’s acquiescence to the dismantling of the “revolutionary” force, done without publicly even acknowledging or calling it a disbanding, the King could move forward with additional “unification/consolidation” plans.

King Victor Emmanuel invited Garibaldi to accompany him to Naples where the results of the Plebiscite on Unification could be declared “official” and King Victor Emmanuel could be declared the sovereign of southern Italy. Garibaldi’s invitation to attend the coronation was not accompanied by an invitation to his troops to also attend. Garibaldi privately either knew at this point or suspected that his promises to his soldiers of pardons and commissions would not be kept by the Piedmont King. Garibaldi nevertheless dutifully attended the coronation ceremony scheduled for mid-November and kept secret the King’s plan regarding the insurgent force.

Once the coronation was accomplished with Garibaldi’s support, Garibaldi was placed on a ship and returned to his island home on Caprera. No explanation to his troops was given on the sudden removal of their “hero” and national legend. The only statement Garibaldi made to his men and the nation was that he intended to return in the fall to renew the campaign against the Papal States. The authority, purpose and intention in Garibaldi’s declaration of return is worthy of great speculation, and will be the focus of this article as it progresses.

Clearly, King Victor Emmanuel II at this point considered himself King of both Piedmont-Sardinia and the Kingdom of The Two Sicilies. This despite the fact that King Francis was still within the Kingdom and had not surrendered. For the new “southern” King a number of major issues and problems were left to be resolved, not the least of which was the ongoing conflict at Gaeta, the status of the conflict with the Papal States, the formation of an “official” Parliamentary union of the north and south and the actual governance of the south.

The two most pressing issues listed above, the siege of Gaeta and the governance of the south needed to be resolved in the most practical way, immediately. It was one thing to hold a self-coronation but the world view of legitimacy required the Bourbon King Francis be dethroned, officially.

As is apparent from the photograph of the fortress an actual ground assault from the landside without supporting naval gun fire would have been suicidal. The fortress had to be substantially weakened before an assault. Gaeta was too strongly defended and positioned to make any such attempt anything but catastrophic in terms of casualties. In addition, while King Francis’ forces were greatly reduced and outnumbered they were among his most loyal. They showed no signs of entertaining surrender. 12,000-15,000 men were more than enough for an effective defense of the position, even against superior numbers.

The French had secretly supported King Victor’s march to the south, and his annexation of those parts of the Papal States that his army had passed through. However, France out of international and domestic concern could not be seen as supporting the outright conquest of the whole of the Papal holdings in central Italy. For one thing, such an attempt by Piedmont could bring Austria into the conflict and force France into a more active combatant role. For another France was a catholic country. With the threat of King Victor’s march southward thousands of Frenchmen had volunteered for service in the Papal army in the defense of Rome. In addition, the Pope could threaten France and its citizens with excommunication if France supported the conquest of Rome. Excommunication was an event that Napoleon III was concerned could turn public support against him.

Garibaldi’s declaration that he would be returning to the south in the spring to renew his campaign for unification by attacking the Papal States had consequences which had both value to and threatened the Piedmont regime. As a result it is difficult to say if the declaration had the blessings of the Piedmont regime at the time it was made.

First, the immediate effect of the declaration was most evident on Garibaldi’s insurgent forces in the south. Those who had been discharged from their supporting role once King Victor Emmanuel had arrived. Most of the insurgent forces supported unification and the incorporation of the Papal States into the civil union of the whole of Italy. They expected to take the unification fight to Rome. 1860 was however a time when irregular volunteer forces often fought for limited time periods. It was not uncommon for soldiers to be discharged for spring planting or fall harvests. Since Garibaldi declared he was coming back to renew the campaign most of his southern insurgents probably thought that the discharge was temporary. As a result rather than initially perceiving the discharge as a betrayal on a promise of enrollment in the new Italian army, etc., it might have been viewed as an informal leave to go home.

This type of leave would certainly have been welcomed by the roughly 1,200-1,500 insurgent volunteers from Basilicata that Garibaldi had with him in northern Campania when Victor Emmanuel arrived. Basilicata is primarily an agricultural State and most of the insurgents would have had connection to its agricultural production. Their labor was needed in the farming process.

Garibaldi’s declaration also would also have put pressure on Napoleon III to resolve the threat to the Vatican, diplomatically and as quickly as possible. It would have also forced Napoleon to pressure and negotiate with Victor Emmanuel to keep Garibaldi’s/Mazzini’s forces in check. Napoleon needed a firm commitment from Victor Emmanuel that he would not encourage an independent action by Garibaldi.

The French and King Victor both recognized that a diplomatic solution to the elimination of King Francis and his forces was the preferred course. France also needed Piedmont’s pledge that it would stop any further attack on Rome. In a sense Garibaldi had set the time schedule for accomplishing the Bourbon defeat. By indicating his return in the spring he had inadvertently set the spring as a deadline. France and Piedmont also felt that a brokered peace agreement that included no further attacks on Papal territory could also get the Vatican to accept Piedmont’s retention of the already conquered parts of the Papal States.

After, the coronation of King Victor in Naples, events took a serious active military turn around Gaeta. On November 18, 1860 a brief truce was arranged between the combatant sides to allow all of the civilian population of Gaeta who wished to leave or who were not participating in the defense to leave. This could only be seen as King Francis hunkering down for a prolonged and brutal siege.

In allowing most of the civilian population to escape Gaeta we can also see the two very distinct perceptions of the situation from the point of view of the two opposing Kings. King Francis was obviously playing a delay game hoping some intervention would come to his benefit. The evacuation of as many non-combatants from the fortress as possible was for him a positive. This would mean fewer to feed, provide for and control. King Victor obviously was preparing for a bombardment campaign and extra civilian casualties would probably not result in an earlier victory or substantial tactical advantage. By allowing the evacuation King Victor could be regarded as a concerned monarch and humanitarian.

As he focused on the commencement of the shelling of the fortress he nevertheless needed to govern the south. This was no minor task as southern Italy represented a doubling of the territory previously under Piedmont’s control. In addition much of his northern territories were only recently added to his Kingdom and his administrative authority there was just taking hold. He had stripped his northern forces to bring his army south. This however, left his northern realm vulnerable to Austrian attack and civilian unrest.

One would think that as much of southern Italy had supported militarily and civilly the revolt against the Bourbons the organization of administration that King Victor would implement would evolve from the revolutionary regional Parliaments that had arisen. The problem with these regional Parliaments especially in rural southern Italy is they contained many pro-Mazzini, pro-republican, anti-Papal State advocates. King Victor and Cavour did not trust the purist element of Mazzinian influence. Therefore he was reluctant to place administrative control in the south in their hands especially while he was distracted at Gaeta.

Instead he structured the administration of the southern Kingdom under corrupt ex-Bourbon Neapolitan administrators and many of the more corruptible Garibaldian authorities planted in Sicily and rural southern Italy. Cavour had sent agents to Naples to align allies even before Garibaldi’s landing in Sicily. Piedmont’s agents had a ready pool of local Neapolitan ministers and underlings who had not backed the revolt until the outcome was discernable, or supported the Bourbons in their darkest hour.

These administrators were for the most part corrupt, manipulative, and exploitive. They were trustworthy to the Piedmont regime only by virtue of their greed and desire for power. To some extent Italy and southern Italy in particular suffer from this decision into the present day.

Since the 1980’s modern Italian historians have been taking a second look at what happened in southern Italy during the Second War for Unification. Some of the problems created, the symbiotic relationships created between political and industrial interests and corruption in the south have been academically revisited. Among the more jaded and damming books on the treatment of the south is Title, “Terroni” by Pino Aprile. In it he makes an interesting observation on the subject of the corruption experienced in the south;

“After more than a century, documents chronicling the corruption, robberies, and massacres of the Unification have been published (or republished, because they had been forgotten). These include diaries of Cavour’s spies that report the names of those accomplices that had been corrupted in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (but also in other annexed pre-Unification states). They also explain the price that “spontaneous revolts” cost to stage, and how deeply involved the other European superpowers were. Those who are scandalized by the revelation of such information shouldn’t be. This is the profession in which, to the horror of the idealists, betters, liars, thieves, traitors and assassins thrive. The worst men in times of peace become the most suitable ones in times of war. It is the time of Cain and the best medals are awarded to those who act like Cain. Pages 113 & 114 “Terroni”

So while some of the decisions and actions of the Piedmont regime can at least be understood from the perspective of the expediency of the time, the continued support, graft and corruption of government officials and business men both north and south was never sufficiently brought under control. This failure of ethics and morality created lasting and now systemic issues especially for the south.

Back at Gaeta the Bourbon defenders after the departure of the community’s civilians came under heavy artillery attack from the Piedmont artillery emplacements on the landside. In response the defenders made two gallant attempts to capture artillery positions from the Piedmont forces. One assault was made on November 29th and another on December 4th. While the attacks were initially successful both were eventually repulsed and proved ineffective in relieving the bombardment for any appreciative amount of time. The siege which had started on November 5th had by early December been going on for a month.

For King Francis and the Bourbon defenders there now loomed only the prospect of a long winter siege without the possibility of resupply. Of course, without resupply, starvation, disease and lack of ammunition would eventually force a surrender. But King Francis was undeterred in his resolute defense of the fortress. The only hope for the Bourbon King was if either France or Austria intervened on his behalf or if relief would arrive from an internal source. The later hope of relief awakened an interesting concern for the Piedmont regime.

That concern for Piedmont became heightened on December 8, 1860 when King Francis issued a Proclamation in a desperate attempt to rally his subjects. His call was to expel the “invaders” of the Kingdom. In the Proclamation the Bourbon King promised additional civil liberties to his people, and urged them to commence a guerrilla war from the countryside.

Of interesting note to this Proclamation, the Bourbon regime had on several occasions during Garibaldi’s campaign in Sicily and southern Italy attempted to rouse the population for support by promising “constitutionally” protected freedoms. None of the “promises” had much effect on either rallying the general population or bolstering the resolve of his troops to fight. Why he thought that proclaiming it once again should be an obvious question. Nevertheless the Piedmont regime took this Proclamation seriously, responding very directly to blunt the possibility. The reasons for Piedmont’s actions will become obvious.

Piedmont’s first response actually began before King Francis’ Proclamation. On December 11th after negotiations involving Prime Minister Cavour, the British and Napoleon III, King Victor Emmanuel ordered a temporary halt to the bombardment of the Gaeta fortress. At the same time a letter was delivered to King Francis at the fortress from Napoleon. The letter urged King Francis to surrender and further advised him that France intended to remove its fleet from it protective position below the fortress. This threat of course meant that the Piedmont fleet would be able to begin an assault from the sea and would bring into artillery range far more of the complex of the fortress.

King Francis remained defiant and refused to surrender. He countered the request and implored Napoleon to maintain his fleet in position so that the dignity of the crown and southern Italy could be maintained during the siege. As this attempt at ending the conflict failed the bombardment was renewed by the Piedmont army on December 13th. The French fleet however remained in its screening position but did not offer any other direct aid to the fortress.

By mid-December almost six weeks after the siege began the effects of the siege began to show on the defenders. Typhus broke out within the fortress. Casualties among the defenders from typhus as well as artillery bombardment now began to mount. King Francis and his men were now confronted by two enemies the Piedmont and a growing epidemic within the fort.

On December 27 Napoleon again attempted to resolve the situation by proposing that King Francis agree to a capitulation in which his and his queen’s safety would be assured. They would be escorted from the fortress under French protection. If King Francis found this offer unacceptable in the alternative Napoleon suggested that Francis agree to a 15 day ceasefire on humanitarian grounds. King Francis again rejected both proposals. The artillery barrage again renewed for another ten days. During that time the rate of fire intensified with the Piedmont artillery firing between 500 and several thousand shells at the fortress a day with about half as many returned by the Bourbon defenders.

Drawing of King Francis II at an artillery battery at Gaeta

As the siege of Gaeta entered its third month Piedmont began to act recognizing that the Proclamation of King Francis did expose a potential liability. As stated in many articles concerning Garibaldi’s campaign in the south, Garibaldi had encouraged many Bourbon soldiers to surrender and go home. Probably somewhere between 60,000 and 70,000 Bourbon soldiers had during the course of the campaign did exactly that. They simply abandoned the fight often with their weapons, and went back to their villages. While this undoubtedly worked well at the time it created a body of men who simply were free to potentially re-engage. Most of these men were not regarded as among southern Italy’s best soldiers but they were a force of men scattered throughout the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

To this potential of an unorganized body of armed men, Piedmont’s decision to disband Garibaldi’s force also came back as a potential liability. Piedmont realized that in their haste to deny Mazzini and Garibaldi a body of men to attack Rome they had essentially eliminated this volunteer National local force. It now was not available as a potential supporting military force that could be used in case the Bourbons began to reform. In essence the bulk of southern Italy was exposed to re-engagement and Piedmont had no force on hand to deal with it. The Piedmont regime saw this as a real and immediate threat to its security.

In part based upon the growing

realization that the prolonged siege was exposing Piedmont to a potential

counter strike from within on January 9, 1861 after more than two months of

siege, Napoleon was once again called upon to help negotiate a surrender. A

ceasefire for ten days between the parties. He hoped that the two months under

bombardment, threat of typhus and winter conditions had been enough to satisfy

King Francis’ honor. He further hoped that the time had helped the King realize

the hopelessness of his position. King Francis again rejected

capitulation.

So the Piedmont regime then attempted to act to reduce the threat of

potential uprising from the roaming former Bourbon troops. As described in

“Darkest Italy” by John Dickie Piedmont attempted the following solution;

“In January 1861, the government proclaimed its intention to conscript elements of the old Bourbon army at a time when the lack of Italian troops on the ground in Mezzogiorno made that policy impossible to implement, thus fostering desertion and crime; the same mistake was repeated in the spring. The politically motivated disbanding of Garibaldi’s southern army removed a force that could have been a powerful weapon against disorder. Instead, the remains of two disbanded armies roamed the countryside; the Bourbon troops in particular swelled the numbers of the bands and tended to give them a legitimist political coloring.” Page 31.

This attempted conscription initially in January 1861 besides being ineffective alienated the former Bourbon soldiers who were distrustful to say the least of the intentions of the Piedmont army should they comply with the conscription. In addition, for those volunteers among the Garibaldi lead insurgents this must have been mindboggling. Here they were not asked to join, having volunteered and the government they supported instead offers conscription to their enemy.

When the latest of the ceasefires ended on January 19th the French fleet withdrew from the harbor. Apparently, the Piedmont regime and its foreign allies realized the situation had to be escalated in order to bring about a more rapid closure. The French fleet withdraw cleared the way for the Piedmont navy to take up position to shell the fortress from the seaward side. Bombardment renewed, now from two directions on January 22, 1861.

The increased direction of fire and increased target acquisition began to pay off. On February 5th, three months after the siege began a Piedmont artillery shell struck the main powder storeroom inside the Bourbon fortress. The resulting explosion levelled about quarter of the fortress causing massive destruction and loss of life, both military and remaining civilian. The explosion and resulting damage was so massive as to even shock the Piedmont forces. The last ceasefire of the siege was declared the following evening to allow the Bourbons the opportunity to try to rescue survivors of the blast buried in the rubble.

On February 10th another letter arrived from the French monarchy. This time however instead of coming from Napoleon and addressed to King Francis it came from Napoleon’s wife and was addressed to the Bourbon Queen Maria Sophie. Apparently the letter was persuasive enough that the Queen convinced her husband to surrender. However, the surrender which guaranteed the safety and transport of the King and Queen by the French to Rome was not fully negotiated and signed until February 13th, 1861. In the three days between the decision to surrender and the signed settlement the Piedmont batteries continued their bombardment of what was left of the fortress.

Piedmont forces entered the citadel on February 14, 1861. Statistics on the siege report that casualties were 829 killed and 2,000 wounded on the Bourbon side together with 200 civilian deaths within the fortress. On the Piedmont side 46 were killed and 321 were wounded. General Enrico Cialdini who had commanded the field army for the Piedmont was later honored by King Victor Emmanuel with the award of the title Duke of Gaeta.

With the departure of King Francis to the protection of Rome the hostilities came to an end in southern Italy or so it might have seemed. As we have written of before sometimes winning the peace is harder than winning the war.

Queen Maria Sophie

King Francis II

King Victor Emmanuel II

When Gaeta fell there were approximately 10,000 Bourbon prisoners of war either captured in the later part of garibaldi’s campaign or the opening of Piedmont’s campaign in south Italy. To this number another 10,000 or so were added with the fall of Gaeta. Fearing a guerrilla war as was called for by King Francis the Piedmont regime could not afford to release these men. They were after all among King Francis’ most loyal. The men were distributed among the prisons of the south but most were sent off to horrid prison camps in the north of Italy.

© San Felese Society of New Jersey