St. Giustino Jacobus (October 9, 1800-July 31, 1860)

By: Tom Frascella July 2015

This month marks the 155th year since the passing of missionary Bishop and San Fele native son Giustino Jacobus, in English, Justin Jacobi. It also marks the fortieth year since his canonization by Pope Paul VI in 1975.

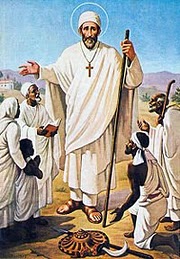

Picture of St. Justin Jacobi missionary to Ethiopia

Our website history has reached the reciting of events that were occurring in Italy and effected San Fele in July 1860. Reference to a saint within the context of the history of those violent and unsettled times may seem a little out of sync with previous articles in this section, nevertheless his death occurred in July of 1860. Therefore I feel it is appropriate to introduce this modern saint into our website story by adding this profile. His story, since he was a man of his times, is directly connected to both the time in which he lived, and our San Fele cultural traditions in which he was raised.

I should start by noting with all appropriate humility for the San Fele community that there are very few places, in comparison to the vast number of towns and cities in the world that can claim a modern era saint as a former citizen. Fewer still if you look to small towns and villages of under 10,000 people. Interestingly, San Fele lays claim not to one but two saints and a third individual who is beatified, the religious step before canonization. Each of these three individuals lived in San Fele in the last 400 years. The three individuals are, by the chronology of their lives, Blessed Francisco Frascella 17th century, St. Gerardo Majella 18th century and St. Justin Jacobis 19th century. I think that in no small part this extraordinary fact of having produced a number of recognized saintly men is related to the town’s long and intense devotion to Mary the mother of Christ. As I have stated the Ma Donna Di Pierno celebration began in 1139 A.D. and is the oldest Latin Rite celebration in her honor as Queen of Heaven in Europe. All three men mentioned above have religious biographies that mention their devotion to Mary. They were raised in the shadow of the Di Pierno shrine and visited the shrine regularly as young boys. Therefore they participated in the celebration of Mary as Queen of Heaven and mother of Christ long before the Roman Catholic rite officially recognized Mary’s unique heavenly status in the late 1880’s.

There are far better sources than this site that delve into the life of these saints including a book titled “Abyssinia and its Apostle” about the trials of St. Justin in Ethiopia which was published within ten years of the saint’s death. What I would like to bring up in this article is the lasting “socio-religious” impact these three men have had well beyond their missions, their lives, and the geography of birth.

I want to bring up the far reaching impact of their lives because with the exception of St. Gerard who is widely venerated worldwide, the other two are far less known. They nevertheless are very important Church figures whose lives resonate in Catholic teaching to this day.

St. Gerard, as many people know is the patron saint of women who are experiencing difficult pregnancies. He is also the patron saint of the State of Basilicata and has been adopted as the patron saint of the Pro-Life movement. There are many churches named in honor of St. Gerard throughout the world. New Jersey has the distinction of having St. Gerard’s American National shrine located at St. Lucy’s Church in Newark. Every year in October his feast day is celebrated at St. Lucy’s parish with tens of thousands of people attending the multi-day event.

San Fele is a small town and has communal characteristics consistent with rural communities located in mountainous regions. These characteristics no doubt contribute to its people including the saints mentioned above. Principally these types of communities due to their relative isolation develop their own cultural traditions. These traditions are sometimes different from the greater regional or national traditions of the countries in which they are located. In addition, the communities are usually tightly knit often closely inter-related by blood both within the town and with neighboring towns. In essence, the communities are in European sociological terms made up of a clan structure. Clan structure is not evidenced in the greater southern regional or national character of Italy as a whole. Most of Italy’s population lives on its coastal plains and big cities, not in rural mountainous areas. So the Lucanian social framework is somewhat different than the social structures of the majority of Italy.

In Italy by custom/culture people have distinct family surnames. Italy is often thought to be a country of close distinct extended “families” a fair observation in most of the country. The clan nature of the relationships in ancient mountainous Lucania as a result, is sometimes not recognized by outsiders who think in terms of family units. I bring this up first because although the three saintly men identified above are separated in time by about three hundred years and have different surnames, their families would have known each other, lived within blocks of each other and indeed been related to each other. So more than coming from the same town they are coming from the same culture and clan.

I also bring the “clan” aspect of the Lucanian region up as it will play an interesting part in the overall events in Lucania in 1860-1866. The time period that this section of our web history is concerned with.

Beyond the fact that there is an underlying clan structure to the culture there is also the fact that the culture itself is layered in a long history of diverse origins. Many of the towns of the southern Apennine Mountains lie close to or on the ancient trade route, the Apennine Way. A commercial highway which was the crossroad of Mediterranean trade for thousands of years. As a result there has been a long cross fertilization and absorption of Mediterranean peoples and culture inherent in each Lucanian community’s history. This manifests in subtle inclusions of customs which are often relatively modest demonstrations of respect and acknowledgement for the people’s diverse heritage. The people are raised with a respect for their unique heritage and its contributors.

As an example of this clan/community relationships at play in the story of these saintly men, San Felese literature points out that Blessed Archbishop Frascella stayed in San Fele for one last visit to the town before departing for his missionary work in the Far East in the mid-17th century. Not surprising that a native son would return for a last visit before travelling half way around the world. But what is interesting is that the literature specifically states that the Archbishop stayed, while in San Fele, with his cousins the Jacobi’s family. So the town culture connects the two men although they lived 250 years apart.

The local literature goes on and also points out in some of the biographies of St. Justin that his family had been residents of San Fele for 300 years by the time Justin comes along in 1800. This would place his family as arriving in the town about two or three generations before the time of Archbishop Frascella. This might seem an odd reference. So what purpose does mentioning this fact, serve and why is it important to know when his family arrived in the community?

To understand in part the information being conveyed one must know that Blessed Archbishop Frascella could/should have stayed on that visit with his own family at Palazzo Frascella. This would have been the expectation for an honored guest of any stature in the town, but more so since it was his homecoming. Archbishop Frascella’s appointment as an Archbishop and Papal Nuncio to Asia was an immense honor.

It placed him among an elite few, a Prince of the Catholic Church, a representative on mission of the Pope himself. His choice to stay at his cousin’s home instead of the Palazzo was not done to imply disrespect to his family. His choice of accommodation was an intentional religious “political” statement meant to be delivered to persons well beyond the borders of the town. The fact that it was a message within the context of its time connects not only Archbishop Frascella and the Jacobis family in the 17th century but also directly connects to the two men’s ministry although those ministries are separated by 300 years. Reading the Jacobis family history dates one can discern that the family arrived in San Fele around 1500 I believe from nearby Venosa. They arrived in the town when many people in the region were targets of the Inquisition.

Part of Archbishop Frascella’s qualification for Papal appointment to the Far East was due to his missionary history of fervent advocacy for cultural respect and regional cultural inclusion. He had developed and demonstrated that approach during his highly successful missionary work in Eastern Europe. His respectful inclusion of local cultural norms and incorporation of the common languages of the eastern regions into religious rites resulted in many conversions to the Latin rite among a population that was primarily Eastern Orthodox Christian and those of the Islamic faith. Incorporating the local language, and translating Latin prayer books may not seem like a radical approach today but in the early 17th century certain fundamental Catholic organizations considered the approach borderline heresy. The philosophy of inclusion and communion of Christian people went against the strict Latin form. His approach established him as a leading early advocate an aspect of what became known as the Catholic Counter-Reformation. His approach to evangelical teaching of course placed him in opposition to some fundamentalists and to the excesses of the Jesuit fueled 15th thru 17th century Spanish Inquisition. He espoused a more ecumenical approach which represented a minority position to those who had a stricter “orthodox” view as to how Roman Catholicism should be practiced and evangelized.

The Archbishop’s appointment by the Pope was geared to try to moderate the excessive actions of the foreign missionaries in Japan and other parts of Asia. Unfortunately his mission to Japan failed as he arrived too late and after the expulsion of western missionaries by the Shogun of Japan. Frascella then spent the next two decades trying to moderate the position of the missions in India. Trying to encourage greater respect, inclusion and reliance in native trained and educated priests, especially in Goa. Again he met overwhelming resistance from European centric missionaries entrenched in the Latin rite.

300 years later St. Justin extended the same spiritual approach in his own ministry upon his arrival in Ethiopia. His approach was considered as radical in the 19th century as Frascella’s was in the 17th. Ironically, Jacobi’s ministry was in fact also directly negatively impacted by the actions of 16th and 17th century Jesuits missionaries in Abyssinia.

To start a discussion about St. Justin we should begin with his family, his parents and his siblings which most biographies in fact do. Again, St. Justin was a member of the culture of San Fele. The Jacobi family had been residents of San Fele by the 1800’s for over 300 years. The family had a longstanding middle-class status within the community. They were considered modestly wealthy by rural Basilicata’s standards, and landed. The family’s wealth however did not insulate Justin’s father Giovanni Baptiste Jacobi from suffering personal family tragedy at an early age. Young Giovanni was orphaned at the age of eight. He and his two sisters spent their formative years in the care of his elderly paternal grandmother and an uncle who was a priest. Giovanni was considered a very bright man but his family circumstance, the need to manage the family estate, required him to grow up fast. The burden of responsibility is cited as the reason that Giovanni despite a keen intellect never attained an advanced degree. As was the custom in those times people married young and Giovanni married Maria Giuseppa Muccia also of San Fele who was the daughter of the town notary.

The marriage resulted in the birth of fourteen children. Large families were not uncommon in the days of high infant mortality especially in rural communities. There were in all eight boys and four girls born in San Fele, including Justin and two sons born after the family moved to Naples in 1813. As stated there was a high infant mortality rate and the couple and their young family were not immune from the experience of tragedy, disease and death. Of the ten sons only five sons survived to adulthood.

From previous articles I hope it is clear that Giovanni and his family lived in a turbulent political time in southern Italy’s history. From the late 1700’s on there were frequent middle-class inspired revolts seeking greater constitutional rights and representation in government. There are hints in St. Justin’s biography that his father Giovanni was an active but insignificant participant in the politics of those times.

Biographies of the saint point out that his Justin’s father Giovanni was a supporter of the cause of republicanism and supported the brief Republic established in Naples the so-called Republica Partenopea in the very late 1700’s. This was a short lived revolt replaced by the suppressive resurgence of the Bourbon regime. Giovanni’s support of republican principles through the four successive regimes of early 19th century Bourbon, then two Napoleon’s proxies and then Bourbon again generally held him under political suspicion as a “possible” republican subversive throughout the rest of his life. Although it was never proven that he was an active Carbonari member, and he escaped arrest where many did not, it is suggested that he was secretly a Carbonari or Carbonari sympathizer.

His supposed political affiliation did not work to advance Giovanni’s political ambitions or advancement in the Neapolitan political bureaucracy. Even after the family moved to Naples in 1813, political appointments and advancement often alluded Giovanni and he had difficulty holding steady employment. As a result the family fortunes waned.

I should point out that both Giovanni Jacobi the father and Justin received their primary educations in San Fele as did probably most of Justin’s other siblings prior to their departure for Naples. Such an education was available in the town and was adequate to prepare young students who showed promise and the skills necessary for placement in advanced studies. Of the five Jacobi brothers that survived to adulthood one became a professor, one a lawyer, and three including Justin became priests. The three that became priests each became respected administrators in their respective orders. I point that out as the post-unification impression created in the Italian media of the time is that southern Italy was backward when in fact the pre-unification educational statistics do not support that conclusion. After unification when schools were shut down or underfunded in the south education and educational facilities suffered. Successive generations became increasingly undereducated.

Justin early on recognized his religious vocation and entered into seminary training for missionary work in 1818 in the Vincentian order’s preparatory seminary in Naples. The Vincentian order would also attract one of his other brothers as well. In the initial phase of Justin’s training he proved to be more than an adequate religious scholar, a humble person of good character, and a Marian devotee. From Naples he was sent to Brindisi for advanced training where he was ordained a priest in 1824. Between 1824 and 1836 Justin devoted himself to teaching, working with the poor and to administrative duties within his order. He was assigned primarily to parishes in south eastern Italy in Puglia. It is during this time that he also dedicated himself to the formation and animation of the “Companies of Charity”, an association of women’s groups dedicated to the service of the needy. From this beginning what became known as the Sisters of Charity would organize. It is also in Puglia in 1831 that a first miracle was associated with his ministry of the sick.

1836 found him back in Naples assisting to the sick and as director of the Neapolitan Seminary where he had begun his studies 18 years before. While in Naples a cholera epidemic broke out. Cholera epidemics were a regular threat in urban centers worldwide in those days. This epidemic became known as the 1836-1837 Neapolitan epidemic. Justin worked tirelessly during the outbreak ministering to the sick of the city without regard for his own health. His efforts and disregard for his own health brought him to the grateful attention of many of the city’s residents, the King, and Church hierarchy. A second living miracle is attributed to Justin by many Neapolitans who related that the end or subsiding of the epidemic occurred at the same time as Justin organized and headed a religious procession through the streets of Naples in honor of the Virgin Mary.

It should be noted that although he worked tirelessly during the epidemic his work did not insulate him from personal tragedy as first his father died in 1837, probably of cholera, and then his mother in 1838. From all accounts, although Justin accepted God’s will in all things the loss of his parents left him with a very heavy heart as he was very close to them.

It was in 1838 while in Naples that Justin met Cardinal Philip Franzoni, Prefect of the Propaganda Fide. The Cardinal had become aware of Justin’s tireless efforts on behalf of the sick and his generous spirit of caring. Their discussions lead to the Cardinal suggesting that Justin lead a small missionary group to Ethiopia as the time seemed right to make an attempt to rekindle missionary efforts. Missionary efforts in that region of the world by Roman Catholic priests had laid dormant for centuries. Justin who had always hoped for a posting in the missions had thought that due to his age such an assignment might be denied him. Justin agreed to the posting but only if his mission was approved by the Superior General of his own Order. Permission was obtained from his order although Justin refused to lead the mission by appointment as a bishop. Justin left on his mission to Ethiopia from the port at Civiaecchia, Kingdom of the Two Sicilies on May 24, 1839 the feast of Mary, Help of Christians.

In all Justin would spend the next 21 years of his life until his death on mission in Ethiopia. At the time of Justin’s arrival in Ethiopia there were two principle religions in the land, Islam and the Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Church. Ethiopia has an ancient Christian tradition of worship which dates back to the 4th century. This makes its Christian community among the oldest in existence. The Ethiopian Christian Orthodox community was under the spiritual guidance of the Patriarch of Cairo, leader of the Egyptian Coptic Church. The Orthodox Church does not recognize the authority of the Pope and is, as a result, not in full communion with Roman Catholicism.

The ancient 1,000 year “schism” between the ancient branches of the Catholic Church East and West not only did not lend itself to cooperation but often caused suspicion and distrust. In Ethiopia this fracture had been made worse by the heavy handedness of Portuguese Jesuit missionaries in the 15th and 16th century. These missionaries Insisted on imposition of the Roman Rite and acceptance of the Pope’s supremacy. The approach had raised the ire of the Orthodox hierarchy in Ethiopia and resulted in the suppression and expulsion of the Jesuits. European religious ministers in general were also viewed by locals as agents of colonialism in the guise of religion. As a result missionaries from Rome and Europe were not accepted by the 19th century resident Ethiopian Church officials.

After Justin’s arrival in Ethiopia he took up residence alone in the town of Adwa. In Justin, the town’s people were soon to encounter an unusual “foreigner”. For one thing he shut himself up in his modest traditional hut in order to learn the Ethiopian languages as he believed that his discourse with the people should be in their language. In time he would master all of the local dialects and become proficient at writing in the native dialects as well. With permission of his superiors in Rome he prepared the first Roman rite prayer books in the native Ethiopian dialects.

He also adopted the wearing of traditional Ethiopian monk’s clothing. Today pictures of St. Justin are often made with him wearing traditional white Ethiopian monk’s dress.

For the first four months that Justin resided in Adwa, Justin made no attempt to preach to the people. The town’s people in turn observed this outsider attempt to learn their language, customs, dress and manner.

It is reported that the people of the town first viewed him with curiosity, then respect because first he came to learn. Eventually, some began to come to him interested in determining what this foreign priest was all about. It was not until he was asked by the people to speak of his faith that Justin began his ministry. What he said to that first gathering of ten people in their native language in his hut was written down and expresses his views and missionary approach. I have reprinted a part of his sermon below so that a feeling for what he was attempting to convey can be received directly;

“The door of the heart is the mouth, and the key to the heart is the word. As soon as I open my mouth and speak I open the door of my heart, and when I speak I offer the key of my heart. Come and see: in my heart the Holy Spirit has kindled a great love for the Christians of Ethiopia…

I have seen you, I have come to know you, and now I am happy…; you are the owners of my life because God has given me this life for you. If you desire my blood, come and open my veins and take it all; it is yours; you are its owners; I shall be happy to die at your hands. Unless it might please you to inflict on me this kind of death which I greatly desire I shall come to comfort you in the name of Jesus Christ. If you are naked I shall give you my clothing to cover you; if you are hungry I shall give my bread to feed you. If you are ill I shall visit you…

If you want me to teach you what I know, I shall be happy to do that. I no longer possess anything in this world: no father, no mother, no native land. Only one thing is left to me: God and the Christian People of Ethiopia. You are my friends, you are my family, you are my sisters, you are my father, you are my mother… I shall always do what pleases you. Do you want me to speak in this church? I shall speak. Do you want me to be silent? I shall be silent. I am a priest like you, a confessor like you, a preacher like you. Do you want me to celebrate mass? I shall do so. Do you not want it? I shall not celebrate. Do you want me to hear confessions? I shall do it. Do you not want me to preach? I shall not preach. Since I have said all this to you, you know who I am. Since I have now opened my heart, I have handed the keys to my heart to you. You know who I am. If you should ask me who I am, I shall answer I am a Roman Christian who loves the Christians of Ethiopia…”

Basically, with those words Justin began his mission in Ethiopia and it could be said established the Ethiopian Catholic Church. He lived what he preached attracting converts by his humility and by the example he set of inclusion and cultural respect. He adapted Roman rites to mesh with Ethiopian religious custom, translated the Roman catechism into the native Ethiopian language and led an exemplary life without scandal or self- indulgence.

During the course of his ministry it is believed he was personally responsible for several thousand converts. During his ministry he accepted the confirmation of the rank of Bishop only because of his belief that the Ethiopian Church should be ministered by native clergy. He needed the authority of Bishop to ordain. In the translation of religious material into native language, the emphasis on native clergy and communion of diverse culture both Archbishop Frascella and Bishop Jacobi had identical evangelical approaches. However, I would say that St. Justin took the emersion into the culture of the people to a level that was quite extraordinary.

Of course as his ministry became more successful it incurred the wrath of competing religious authority especially that of the Orthodox Christian authorities. Eventually there were attempts to separate him from his converts by imprisonment and house arrests. Many of his followers were arrested as well.

Some died in prison some like Justin had their health broken. Again the book “Abyssinia and its Apostle” gives a detailed examination of the trials and tribulations of his ministry in Ethiopia. It should be noted that Justin’s emersion into Ethiopian culture and society was so complete that to this day Ethiopians Catholics do not consider him a foreigner but rather an Ethiopian martyr and saint. I read in one publication that even today the most common Christian name among Ethiopian Catholics for both males and females is Justin.

It was clear to Rome from the outset that Justin’s ministry in Ethiopia was successful in his lifetime and continued to be successful moving forward. His approach to bringing the word of Christ to the masses was noted, discussed and debated within the Church Hierarchy for decades.

Although, his approach was not embraced by all, the approach would eventually did find acceptance in the emergence of Catholic thought in the 20th century. It took Vatican II called for by Pope John XXIII to start to bring the principles of this more open evangelical ministry to light. This spirit of evangelical Christianity espoused in Vatican II which Catholics have experienced most notably at the time, was the shift from Latin masses to masses conducted in the common language of the people. This has been followed by a steady increase in promotion of “native” non-European priests to positions of authority especially in their native countries.

Subsequently the role and acceptance of the body of culture in ecumenical concert was extended in the apostolic exhortation of “Evangelii nuntiandi” of Pope Paul the VI. The exhortation drew heavily on the examples found in the works and acts of the ministries of Frascella and especially the later ministry of Jacobi. Their ministries and their success were well known to Pope Paul as well as other Church leaders who helped draft the exhortation. Among those drafters was included a young Polish Cardinal who would go on to become Pope John Paul II. It was obviously not an accident that St. Justin was canonized by Pope Paul VI on October 26, 1975 and the exhortation was issued on December 8th of the same year. In part St. Justin’s elevation to saint at that precise time was meant to acknowledge his work and contribution to modern Catholicism.

For those who are interested in the subject of St. Justin’s impact on modern Catholicism there is a very well written thesis by William Clark, C.M. The thesis was written while Clark was in a religious Masters’ program at Angelicum University, Rome in 1984. The thesis is titled “The Ecumenical Implications of the Ministry of St. Justin De Jacobis in Ethiopia, 1839-1860”. It can be found on line.

So, I think that it is fair to say that due to their cultural upbringing, the manifestation at its core of a heritage of inclusion, the ministries’ of St. Gerard, Blessed Archbishop Frascella and St. Justin Jacobis have had significant and powerful influence on the direction of modern Catholic evangelical thought and ecumenicalism. These men have by their lives and example provided a legacy that we should all be proud of.

© San Felese Society of New Jersey