Rural Southern Italy/Lucania Placed on Trial 1864

BY: Tom Frascella May 2017

As discussed in the previous article, the Legge Pica law which was passed in August 1863 specifically targeted Italians in southern rural Italy. The law did not apply and was not enforced in other parts of Italy. The law was a civil “national” legislative codification of the martial laws previously imposed by the Piedmont Monarchy/military also only applying in southern Italy starting in 1862. Despite the appearance as a legal legislative act, these “new” limitations on civil liberties were unprecedented in Italian politics and contrary to the “promises” of a unified Italy with only one set of equally applied laws. Individuals accused of breaking the Legge Pica laws continued to be adjudicated in summary non civil proceedings. These proceedings were mostly conducted by military tribunals as they had been from the previous, unconstitutional, martial laws which they were supposed to replace. This period of the abolition of rural southern Italians civil rights lasted from 1862 thru as late as the 1880’s. Yet despite the fact that tens of thousands of rural Italians were unjustly imprisoned, without due process hearings, and tens of thousands more executed there has been little historical focus or acknowledgement that such events occurred. The average Italian-American 80% of whom have southern Italian roots simply have not been introduced to these historical facts either in their education or in family narratives which often would not include these painful remembrances.

I hope over the next several articles to not only shed some long overdue light on the events and actions of the Piedmont regime toward the south, but also show some of its lasting consequences of both the physical and psychological impacts doled out. Among those lasting consequences for San Fele and Lucania was an early “forced” mass exodus and immigration to the Americas starting in the early 1860’s.

That the southern population was forced to flight becomes all the more understandable when one realizes that the new laws were backed up against the civilian population with a steadily growing number of Italian army troops stationed in the south as “enforcers” of civil order. In all, the south had seen a growth in the number of, primarily northern and mercenary “occupying troops”, which grew from about 70,000 in 1862 to about 125,000 by the end of 1864.

National forces positioned in the south of Italy by 1864, armed with the Legge Pica law had what was necessary for implementation of all out suppression of civil liberties. Piedmont military forces stationed in the south of Italy began to wage a war on the rural inhabitants of southern Italy. Essentially this war had four major components which were designed to be as much psychologically vindictive as militarily punitive.

First, there was the actual military campaign against actual, in the field, insurgents. While these men had proved effective resistance fighters in small scale operations they were never a major military threat to the Piedmont regime. In actual numbers the resistance fighters never numbered more than 10,000 combatants inclusive of the entire south. So at their peak the Piedmont forces held at least a 12 to 1 numerical advantage and a staggering supply and equipment advantage over the poorly armed and equipped southern resistance fighters.

Second there was the military campaign against southern civilian noncombatants. This campaign was designed to separate the insurgents from food supplies, recruitment of disenfranchised young men and finally from valuable “intel” which could be used against the occupying Piedmont military. Since rural southern Italy is highly “clan” based culture this campaign was an attack on the very “family” structure and fabric of southern Italy. The campaign by Piedmont to deny the resources of the insurgents became a campaign against the insurgents’ families, their communities, and culture.

Third, it was important to the Piedmont regime’s P.R. campaign that there be a very public denigration of the people of the rural south. The insurgents could not be seen either by their families or the public at large as “heroes” or victims. Piedmont was concerned that too often, small bands of resistance fighters became objects of legend, local Robin Hoods so to speak in their native territories. Such a romanticized version of their efforts could not be allowed to develop. The insurgents had to be seen as not only the enemies of unification but even better enemies of humanity itself. The vilest of sub-human humanity, devoid of morality, decency, culture and redemption.

Fourth, the campaign had to be financed on the backs of the victims less the costs render the campaign unpopular among northern supporters. Further when the campaign concluded the rural south had to be left in a position where it could not rise again. One way to do this beyond the looting, pillaging and destruction of towns and villages was to systemically destroy the educational and industrial resources of the people of rural southern Italy.

The beginning of the End of the Insurgency

As we have seen between the end of 1861 and the beginning of 1864 the insurgents, especially in Basilicata had been able to out maneuver the federal troops sent against them. Remaining in elusive small bands hiding in the underpopulated mountainous terrain the insurgents were a difficult target for tradition military tactics. However, by 1864 the policies and troop build-up began to turn the tide in favor of Piedmont. This is not entirely surprising given that the entire number of insurgents actively engaged in Basilicata probably numbered no more than 2,000 poorly armed scattered men. As the Piedmont forces tightened the noose restricting the insurgent resupply of men, arms and food, the insurgents became more desperate and more prone to take greater risks. With those risks came greater casualties.

For example, early 1864 saw a number of the most notable of the brigand commanders in Basilicata killed. Among them the dashing commander known as Ninco Nanco. Ninco Nanco actual name was Giuseppe Nicola Summa. He was a native of Lucania born in 1833 near the town of Avigliano. He quickly rose to prominence among the insurgents, joing the cause in 1861 in Basilicata. From 1861 thru 1864 he was considered Carmine Crocco’s second in command. Ninco Nanco was cited regularly as playing pivotal roles in each of Carmine Crocco’s early victories against the Piedmont regime in 1861-1863. In fact, both Carmine Crocco and Ninco nanco carried the same 20,000 lire bounty, issued by Piedmont, on their heads. In 1864 Ninco Nanco was just 31 years old. His death, like many of the insurgent deaths of this time underlies the effectiveness the military build-up and of the psychological war the north was waging. That psychological toll was beginning to breakdown the will of the local population.

At the time of his capture and execution Ninco Nanco was moving about in territory completely familiar to him near Avigliano his birthplace. This was an area where he had many contacts and knew the lay of the land. In the early years of the resistance his movements would have been completely protected by a code of silence among the local population. He was after all one of them and probably related thru a vast social network to most of the community, including members of the local National Guard. As we previously described in the early stages of the resistance the local National Guard often supported the resistance. However, by 1864 external pressure had changed the equation. As a result one night when he and two companions, one of whom was his brother, were resting in an isolated farmhouse in the countryside, the farmhouse was surrounded by local National Guard troops.

Obviously his whereabouts were betrayed as it was clear from the reports of the conflict that the authorities went to this isolated farmhouse anticipating his presence as opposed to randomly encountering him. After a brief exchange of gunfire the three men were captured, alive. The men were immediately and summarily executed on the command of the local National Guard commander.

It is generally believed or reported in writings at the time that Ninco Nanco’s strategic position and access to support was deteriorating in the region. This was made worse when another local commander defected and went over to the Piedmont side. This commander’s name was Giuseppe Caruso. In the customary story telling of the time and region, this betrayal was attributed to some falling out over a women. Southern Italians and those writing about southern Italian affairs seem to like to allege that a “women” was somehow involved in most treacheries. This is probably not true and his defection was more likely the result of the tightening of the Piedmont noose around the families of known insurgents, including Caruso’s. Legge Pica allowed government troops to arrest family members including mothers, wives and daughters as complicit. Such arrests could result in all sorts of punishments ranging from execution, rape and imprisonment for up to twenty years. It was reported that information that Caruso allegedly supplied to local officials in exchange for “leniency” had led to the capture and execution of a number of insurgents in 1864.

An odd part of the story of the capture and execution of Ninco Nanco is that normally the capture of such a well-known brigand would have led to quite a public spectacle and staged execution. This was followed by an elaborate rewarding of those involved in the capture for their military accomplishment. However in this case Ninco and his companions they were executed immediately by the National Guard commander in the field far from a public display. It was rumored that the National Guard unit and commander that captured him, executed him immediately because the commander and his unit had formerly worked with the insurgents. They were afraid of being found out. Remember that it only took an assertion of complicity to find ones-self at the wrong end of a firing squad rifle. Rather than risk Ninco Nanco denouncing the commander’s previous disloyalty to Piedmont it may have been considered expedient to silence him before bringing his body in as proof of his death.

Although the Piedmont high command was denied the showcase execution and the psychological opportunity a public execution would give, there was a back-up plan. The psychological war being waged, especially for such a notorious criminal such as Ninco Nanco, required a show of degradation of the “criminal” even in death. Among the techniques employed by the Piedmont commanders in southern Italy was public humiliation of the corpse, after death, often these atrocities were memorialized with degrading photographs of the corpse. These photographs were then widely published and served as further warnings to the public and to the families of those killed.

In the case of Ninco Nanco his corpse was photographed at the time he was killed at the farmhouse. Although this photograph was not of his degraded corpse as some that may be because it was taken before the body was turned over to the Piedmont regulars.

Photograph taken at the site of capture of Giuseppe Summa aka Ninco Nanco’s corpse

After Ninco Nanco was killed his body was taken to his birthplace and hung up in the town square for several days. It was allowed to decay in the sun and be picked at by scavengers. From his home town the degraded corpse was taken to the Lucanian Capitol of Potenza for further display and degradation before finally being buried there.

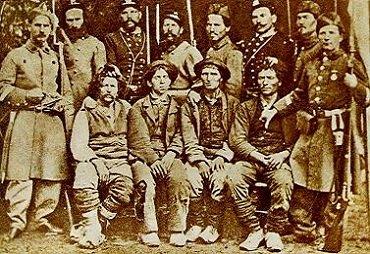

Degradation of corpses was an integral part of the program of public humiliation of the people of the south during this period. Below is a photograph on Italian National troops standing around four freshly executed “trophy” insurgents, whose bodies are propped up in a sitting position. Whether the four nameless victims were actual insurgent fighters or merely accused of being sympathizers was irrelevant. It is the breaking of will of the people and degradation of their loved ones that is key to what is occurring.

Photograph of National troops

Another example, of the terror techniques employed by the Piedmont commanders in southern Italy was that summary execution of “suspected” insurgents or sympathizers conducted in the countryside, far from public display. Often these countryside executions were carried out and the victims buried in unmarked graves. Their families unable to confirm their deaths were left to speculate as to the fate of their loved ones. Imagine the psychological terror and impact of such executions. A loved one leaves to work the fields in the morning and is never heard from again. Often such executions received no “official” recording and therefore “officially” never happened. This is one of the reasons that the estimates of the number of southern Italians executed between 1861 and 1900 by the Piedmont regime varies from as “low” as 50,000 to as “high” as 1,000,000.

Photograph of trench were executed insurgents were buried.

Such degradation even after death was not reserved for just Lucanian men. In order to maximize the psychological terror among the civilian population in general, and the insurgent families, in particular, Lucanian women, young and old suffered similar fates. The actual number of Lucanian women that lived with and in some cases fought alongside of the insurgents were relatively small. Italian women of this time were generally considered more passive, the weaker sex. The fact that rural southern women were even in small numbers taking up arms both infuriated the regime and further confirmed the “moral’ abyss that Piedmont asserted southern Italians lived in. At the same time, in certain quarters women taking up such roles fascinated the public. The legend of the “brigantesse” began to emerge. Piedmont officials went to great lengths directing efforts to insure that no sympathy or heroic aspect attached to brigands of any sort but especially to women. In this regard special efforts by Piedmont were encouraged relative to the campaign on the female component of southern Italian insurgency.

In the case of women, whether actual combatants or just suspected “abettors” including family members there was the additional omnipresent threat of sexual assault, molestation and sexual post-mortem abuse of corpse added to the likely Piedmont military terror tactics. Most women executed were photograph post mortem nude with the evidence of their physical molestation at the hands of northern Italian troops proudly displayed. The photographs were then printed in local newspapers and also posted in town squares. Probably, one of the more notorious examples of this, is the case of Michelina De Cesare.

Michelina’s image appears regularly in writings about the female “briganti” of southern Italy. Her image is sort o the poster image of a rural southern Italian Brigantesse. I think primarily the case because her photograph is in classic southern Italian dress with her leaning on a long rifle. So she has become something of the cultural iconic image of the female southern rural Italian insurgent. She was an attractive young women, age approximately twenty at the time she took up the insurgent life.

Photograph of Michelina De Cesare

Born in Caspoli, Abruzzo in 1841, at age 20 she is said to have met and fallen in love with one of the insurgent commanders by the name Francesco Guerra. Again, Italian narratives always seem to include some romantic aspect. Obviously, she is associated with his band but he operated primarily in a territory outside of her home region. . There is no explanation as to why she so fiercely took up the insurgent cause or how she met Guerra. For seven years she was an active and participating member of his gang. It is important to note that she was still active as an insurgent in 1868 so there were still insurgent holdouts active in the mountains well beyond 1864. The importance of noting that resistance did continue matters for understanding what policies the Piedmont regime employed in the late 1860’s and thereafter and that the tactics of suppression continued to make new “briganti” victims.

To clarify many “authorities” claim that Legge Pica only existed in Italy from 1863-1865 when it was repealed. While that may be technically correct, in fact Legge Pica was based upon the actions of the military already being employed in the south starting in late 1861. In addition after the law’s technical repeal the military’s suppressive actions did not change and the abuses continued into the 1880’s “without color of law”.

Michelina from all accounts fought along-side for her guerrilla boyfriend in the field and did not shy away from the physical dangers associated with the cause. As such she attained a level of status that was unusual for women of the day and was a bit of a local folk hero among rural women. Nevertheless the story of the end of Michelina arose in familiar terms associated with many insurgent captures and executions. Her band was camped in August 1868 on the slopes of Monte Lungo, Campania. This was familiar and “home territory to the band’s leader and probably considered “safe” ground. Like the end of many of the insurgent gangs, under extreme pressure from the Piedmont forces eventually the gangs’ whereabouts were betrayed. The Guerra band at the time consisted of about a dozen individuals including Michelina. Under cover of darkness and with a thunderstorm in progress a large number of Piedmont troops were able to successfully surround the Guerra band without discovery. The Piedmont force then attacked the insurgent force and a brief gun battle followed. During that skirmish insurgents Francesco Guerra, James Ciccone and Francesco Orsi were slain. Michelina however was captured alive.

What followed for Michelina was a day of violent torture at the hands of the Piedmont troops. Supposedly the purpose of the torture was to seek from Michelina information regarding other insurgent bands whereabouts. Michelina withstood the brutal torture refusing to cooperate with the soldiers or betray any information she might have. When the attempts at physical torture failed it was followed by the violent gang rape of Michelina by the soldiers. When that also failed to elicit any information she was strangled to death.

As previously mentioned those acts as brutal as they were never condemned or denied. In fact they were highly publicized and praised. They needed to be publicized for maximum terror impact, and to demonstrate to the rural population what their fate would be if they shared or sympathized in her cause. So her naked and brutalized body was photograph in order to further terrorize the southern Italian population. A powerful statement by the Piedmont authorities especially to the rural southern women of the region.

Photograph of Michelina De Cesare corpse.

In the midst of this unprecedented crackdown and suppression of the civil rights of the rural southern Italian community, Piedmont maintained a necessary narrative in order to deflect European public opinion and condemnation away from them as oppressors. The way determined by Piedmont to accomplish this was to create an impression of a mass public guilt shared equally and inherent in the southern population’s very soul.

The capture of the insurgent agent La Gala group the summer before, provided a ready-made opportunity within a highly publicized international forum to play out that narrative. In the La Galas Piedmont had several notorious and certified southern insurgents from northern Campania, the south. Further, it could be proved that these men in particular had been working closely with the Bourbon regime exiled in the Rome. They had left upon their mission to secure recruits from Rome. They carried forged identity papers issued in Rome. There was evidence that they were on a secret mission for the Bourbons. All of this could only have been arraigned with at least the tacit approval of the Pope.

As we previously discussed in past articles their capture with the aid of French officials provided the European and especially the Italian and English press great opportunity to disparage both the Bourbons as aggressors and the Papacy as anti-civil liberty, anti-republican. The treaty between France and Italy protecting from extradition political arrestees however caused the trial to focus on the La Galas as “criminals” rather than “political” activists. Therefore the trial itself focused on the insurgent cause in the south, of which the la Galas were part, as a criminal enterprise. The trial focused on the La galas known or alleged acts of violence in the south as “depraved” acts of criminals. Allegations of merciless murders of soldiers, civilians, even priests were attributed to the la Galas and by association as common to all southern brigands. One on the many charges, which actually could not be proved, was that the insurgents “ate” their captives. Again the purpose was not to obtain the truth or justice but to further a narrative that cast the victims of Piedmont’s civil oppression as the perpetrators of unspeakable subhuman acts. The trial was a staged showcase for anti-Papal sentiment, anti-Bourbon and anti- southern Italian sentiment.

The result of the trial and its foregone conclusion of a guilty verdict was threefold. First it accomplished the linkage of the Bourbon and papal causes and the two entities continuing effort to reestablish the Bourbon Monarchy in the south. By linking the two it placed the Piedmont regime and its oppressive actions in the position of claiming their actions in the south as necessary defensive acts preserving the will of the southern people for unity. Second, it forced the Vatican to back off its support of the Bourbon cause in order to maintain its support for it own independence from Piedmont which relied on French support. Third the trial succeeded in casting the whole of the insurgent movement as violent criminals inherently degenerate and immoral on the world stage rather than acknowledging their legitimate political grievances or political position.

By the end of the summer of 1864 any possibility that the insurgent cause in southern Italy would find support from any international source had disappeared. Faced with the unprecedented assault on their families southern insurgents, including those from Basilicata began to surrender to, usually National Guard units. To be sure these types of mass surrenders were not in character with regional history. For generations, those maintaining a life outside the law had survived, sometimes decades, living in the mountains or by fleeing to other countries. But this was not really an option that the insurgents had in this moment in time.

For one thing the insurgents were faced with the threat to their families. Continuing to hide up in the mountains or to seek refuge in foreign countries did not lessen the threat to their families. That is why many choose to surrender, in the hope that their families would survive or at least not be punished. They surrendered knowing that they faced execution or at the least 20 years in prison. Of course, in addition to the “punishment” allotted out by the Piedmont regime there was no one to publicly dispute the label of “criminal” placed on them by Piedmont as well.

One individual among the insurgents of Basilicata who did not surrender was Carmine Crocco, whose fate, as it is enlightening, I will discuss in the next article.

© San Felese Society of New Jersey