A Penny for Your Thoughts

By: Tom Frascella November 2016

Throughout our San Felese web history, specifically as it relates to San Felese immigration to the U.S., I have noted that I often rely on the stories told of my great-great-grandfather Vito’s journey and experiences. I have found that by following the timeline of his actions I am constantly led to specific historic events, especially in his native Lucania. He was as a member of the closely integrated San Felese community of the 19th century and therefore directly connected to the events impacting the entire region.

As he has been long considered the first of the community to settle in Trenton and among the first of many who came to the U.S. it is obvious that those historic events were impacting him early and in a life changing way. Those personal impacts necessitated that he leave family and friends and make the long journey to America as a “political” refugee. Most Italian immigrants arriving in the U.S. between 1820 and 1880 were classified by the U.S. as “political” refugees. In the aftermath of the 1861 unification his journey actually establishes a reliable time line for events that were to pressure an ever increasing immigration from Lucania/San Fele and southern Italy as later articles will establish.

Vito arrived in the U.S. from Italy in early 1862. From the immigration research done by Prof. Stia on San Fele immigration we have documented that in just the years 1862 and 1866 alone almost 600 men arrived in the U.S. from San Fele. U.S. census records indicate that in that same period only about 10,000 people arrived in the U.S. from all of Italy. That means that during that time frame at least 6% of all arriving Italians in the U.S were coming from San Fele, a town of only 10,000 people. In addition that number of men leaving in that five year period represents between 25 & 30% of the entire adult male population of the town and around 50% of the adult male population between the ages of 16 and 45.

Over the course of the next 12 articles, including this one, I hope to lay out some of the conditions that created this extraordinary exodus.

In the last article, I concluded with some of the reasons that Vito might have found it necessary to leave San Fele in December 1861. There was an active and violent civil war between pro-Bourbon and pro –Piedmont factions and being caught up on one side or the other could be life threatening. But a physical threat to his life and safety can be implied it doesn’t really explain why he choose to come the U.S. as his place of exile/refuge. It also doesn’t explain how of all places he wound up almost immediately after arrival in the U.S. in Trenton, NJ.

From everything I have read in the immigration statistics available, the U.S. was not a common destination for Italians in 1861. Between 1850 and 1860 the U.S. census and immigration statistics place the total number of people immigrating to the U.S., born in what is now Italy, at only 10,000. Further, nearly half that number didn’t stay but returned. Of the 5,000 that did remain most were from central and northern Italy and many of them settled out west including California which was experiencing a population boom as a result of the California “gold rush”.

Most Europeans seeking refuge, even political refuge, in the 19th century would flee to other European countries. European countries are closer and offer cultural similarities that would have provided an advantage to a romance language speaking southern Italian. In 1861 the U.S. was expensive and difficult to reach for the average southern Italian. The U.S. was engaged in a violent civil war of its own, and the predominant language was English. To that, it was unlikely that in the vastness of the U.S. that southern Italians could find without significant English proficiency other southern Italians even if they were here in small numbers.

However, according to both family oral history and those articles about Vito’s arrival written and published almost 100 years ago, he emigrated from Naples and arrived in New York in early 1862. He then almost immediately was able to contact a fellow San Felese, Carlo Sisti, who had arrived only months before and was already working in Morristown NJ. How he was able to locate Carlo suggests that there was some sort of network of information available to Vito which was keeping track of where Italian ex-patriots were living and working. Further these sources could direct Vito’s movements from New York City to Morristown. Carlo was already employed on a masonry labor crew working on a bridge project in Morristown NJ. But this project was wrapping up and the Masonry contractor, whose business headquarters was out of Trenton would be returning to the city. With Carlo as a contact he was able to secure an offer of future employment for himself with that same employer.

Vito then travelled to Trenton to establish temporary lodging and await the masonry crew’s return to the city. Survival in Trenton would seem to present difficulty for a non-English speaking young man. Census records indicate that there were probably fewer than 30 Italians in all of New Jersey and probably at most two in Trenton in early 1862. From my understanding as related in family stories it was not Vito’s or Carlo’s Italian heritage that was propelling him in the U.S. or guiding his movements. Rather it was an aspect of their shared Italian politics. Neither man was by trade a mason or had worked in construction so it was not skill that allowed them to find work in that field or directed them to a non-Italian contractor for employment.

I guess I should take the time to explain, how it was that Vito was talked about at all in the Trenton San Felese community. As the first of what would become a large San Felese-American community in Trenton, Vito was a figure whose presence came up in conversation in many respects. Especially as to his contribution to the location, organization and early opportunities that helped the subsequent early San Felese community survive. Vito’s life story was unusual in that people born in 1840 as Vito was, generally lived only forty to fifty years in the 19th century. As a result of the lack of longevity there was not much opportunity for the first and second generation after them to directly interact. However Vito lived to be almost eighty and so most if not all of both the next two generations, my grandfather’s generation, not only knew him but interacted with him as adults. So when they would talk about him it was through first hand interaction and conversations.

I should also point out that Vito had 29 grandchildren all born in the U.S. who survived to adulthood. Being a major figure in the family and community made him a person of interest and note. The size of his family made family gatherings frequent and lively. Often, in the telling of “old” stories, Vito’s name would come up as everyone seemed to have some story about him and his life. Family and community conversations and even articles written concerning Vito often involved discussions about Vito’s Italian pre-immigration and American post-immigration politics.

However, before I begin to discuss some of what was said about Vito and his initial arrival in the U.S. I would like to mention another and distinct individual’s arrival to the U.S. from the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1861. Again with this person as with Vito, their arrival would ultimately be intertwined with politics especially 19th century Italian-American politics.

Rev. Dr. Januarius Vincent De Concilio

According to his biography De Concilio who is said to have been born in Naples and therefore of southern Italian origin, was about four years older than Vito when he arrived in the U.S.in 1861. His destination was also New Jersey although it was Newark NJ, not Trenton. Despite his relative youth, 26, he was already an ordained priest and an accomplished Catholic theologian, an Italian intellectual. Dr. De Concilio belonged to the theological school known as Thomism or those influenced by the teaching of 13th century Lucanian theologian Thomas Aquinas. He had been recruited by Bishop Bayley, first catholic bishop of New Jersey, from a seminary in Rome to teach theology at the newly established seminary of Our Lady of Lourdes in New Jersey. This seminary would become affiliated with Seton Hall College, which also was established by Bishop Bayley.

Bishop Bayley started the college to promote education among the growing number of Catholics, mostly German and Irish in the State. Bishop Bayley named the college after his aunt Elizabeth Seton. In the roughly 20 years that Bishop Bayley was New Jersey’s first Bishop the Catholic population of the State doubled.

Again, in Bishop Bayley recruitment of Dr. De Concilio we see a different view as an Italian is being sought out to come to America. Father De Concilio’s worth/value was his intellectual and professional training and expertise as well as the fact that he was multilingual. Among the many accomplishments of Rev. De Concilio during his long ministry in the U.S. is that he is credited with producing the first draft of what would become known as the Baltimore catechism.

For this and a number of other reasons Rev. De Concilio was an important figure in the evolution of American Catholicism and one of a small number of Italian priests and nuns, a dozen or so who came to the U.S. between 1850 and 1890. These priests and nuns were individuals of extraordinary intellect and energy. Many initially arrived to serve the needs of German and Irish Catholic immigrants. Too often their contributions and accomplishments in the service to these immigrants in America have been overlooked. Subsequently as more Italian immigrants began arriving they sought to offer the same help and expertise to them as well. They not only sacrificed greatly for the cause of Italian immigrants but in the process forced changes on American Catholicism. Especially the way it handled the masses of arriving eastern and southern European immigrant Catholics and their traditions of faith. Many of these individuals literally sacrificed their careers within the Church to accomplish what needed to be done for these immigrant to feel included and welcomed in the American Catholic Church. I don’t know if Vito knew the Rev. De Concilio, a possibility, Vito did however interact with other Italian priests in New Jersey and New York who would have known him. De Concilio’s work, and his relationship with Bishop Bayley had direct consequence within the Catholic Church in New Jersey/U.S. and directly affected the San Felese community as it would develop during the second half of the 19th century in NJ. So I mention him here and I intend to bring him and his work up again in future articles.

Coal Burners

Getting back to 1861-62, it was not Vito’s Catholicism that brought him to America or New Jersey, some might argue it was the opposite of that reason. As previously written over many preceding articles Italy gave voice starting in the early 18th century to a somewhat regionalized political movement advocating greater civil rights and constitutionally established liberties. Eventually this movement moved toward encouragement of the formation of “republics” whether constitutional monarchies or democratic republics among the Italian States. In southern Italy a democratic republic briefly was established in Naples at the end of the 18th century, 1799. Because these movements, which were driven by middle-class and lower upper-class individuals were so regionalized their successes were few and brief in Italy in the 18th/ 19th centuries. But the flames of liberty and self-determination never completely went out. Most European Monarchies of the era easily defeated the occasional pro-Constitutional revolts. The suppression resulted in the pro-Constitutionalists being forced to secretly meet in small clandestine units/cells. Many of the political views supported by these groups were also supported by Masonic societies both in Europe and in the American Colonies/ later the U.S. In early 19th century European advocates for the cause of civil liberties became known as “Carbonari”, coal-burners in southern Italy and then throughout Europe. This because they gathered in small secret meetings plotting their political moves and spreading their advocacy for democracy. Admission into these small secret but loosely connected groups, “cells”, usually required several years of probation and close indoctrination. This unless you were a Mason in which case admission was automatic. In Italy like the American Colonies many of the advocates for liberty and republicanism were Masons and the movements were closely associated and supportive with each other.

This article is not intended to be a dissertation on Freemasonry in either Italy or America. However freemasonry existed in every region of Italy, and specifically southern Italy for at least a century and a half before the Second War of unification in 1860. However, the subject needs some discussion as it is important to the politics of southern Italy and our San Felese immigration to the U.S. as it developed from 1862-1865.

First, I should say that there are virtually no surviving records of early Masonic groups or membership existing in southern Italy or specifically San Fele/Lucania. That is not an accident, it is precisely the way it was intended to be, by those Masons involved. Absolute secrecy was necessary as advocating against the monarch was at least punishable by imprisonment and at worse death. . As far as I know the Italians invented the “cell” structure for protection/secrecy of the Masonic organization’s affiliates even limiting those who had knowledge of members of other cell’s membership. This cell structure has been successfully adopted for use by many “resistance” groups and radical political groups subsequently.

As far as can be determined there was a Masonic organization in residence in Naples at least as early as 1728. This is known because the Masonic seal for that “lodge” known as the “Perfect Union” was found. There are also records indicating that a second “lodge” was established in Naples which was chartered out of London in 1731. Again, there are no surviving records of membership. Helping fuel the secrecy of the organization in Italy was that their activities and their political beliefs were considered by the regional authorities as subversive to the established order. In addition, the Vatican considered them subversive/heretic to the authority of the Church/Pope and therefore anti-Catholic. The first papal condemnation of the Italian Masons as anti-Catholic was issued by the Pope in 1738. So Italian Masons, especially in the south, rarely would allow public acknowledgement of their association, or expose themselves publicly as Masons. Such exposure as I said could result in criminal charges or excommunication.

Historical Italian documents also allow us to piece together that a “third” lodge was formed in Naples in 1751, the same year as the Papal Bull of Pope Benedict XIV titled “Providus Romanorum Pontificum” which further reinforced the religious based condemnation of the organization. Within months of the Papal Bull Bourbon King Charles VII issued an edict prohibiting Freemasonry in the Kingdom of Naples. However the edict was rescinded about a year later and the practice and membership in Freemasonry was allowed in the kingdom of Naples from 1752 thru 1775 but remained relatively secret.

In 1775 the Bourbon King’s Prime Minister convinced him to again ban the organization from the Kingdom of Naples. However, this ban lasted only a year as well. Freemasons were allowed to organize in southern Italy between 1776 and 1781. I would note this is during the time of the American Revolution led in substantial part, by American Masons. Another ban was instituted in the Kingdom of Naples in 1781 and was in effect for two years. While this ban was technically lifted in 1783 it was done with so many restrictions that any public display of Masonic involvement ended in the southern Kingdom and the organization went completely underground. It stayed underground but active and was gaining strength as it advocated for republic/constitutionally based government during the remaining part of the 18th century.

The spirit of “republicanism” again raised up during the First Republic revolution in France. Encouraged the republican advocates rose up in southern Italy and briefly established a “republic” in Naples called the Parthenopean Republic after the first Greek colony which settled what became in time, the city of Naples. This was very short lived and the Bourbon King came back in power. He renewed efforts to crush all those suspected of republican sympathy.

The only other period of time during which some Masons were openly practicing in southern Italy was during the French occupation of Naples 1804-1814. Suppression of the organization and therefore secrecy of membership continued in southern Italy up to Garibaldi’s arrival in 1860. Garibaldi and Mazzini were both well-known northern Italian Masons. While they supported the House of Savoy in establishing a constitutional Monarchy in Italy both were known to favor a democratic republican form, especially Mazzini and the total unification of the Italian peninsula. This included the Papal territories with the elimination of the Pope’s authority in secular politics.

This brings us to Italy as it existed shortly after the collapse of the Bourbon Monarchy and the “Unification” of April 1861. Many of those who fought for or supported Garibaldi in Sicily and southern Italy against the Bourbons had Constitutionalist republican leanings, raised on the ideas of Mazzini’s “Young Italia”. Many were secretly members of the Carbonari/Young Italia movement. Many were in addition Masons. As other articles in this history have outlined Garibaldi, after basically handing southern Italy to the Piedmont regime, was shipped off by the King and Cavour to his island home at Caprera. There his activities while not restricted were closely monitored by the regime. Mazzini was essentially persona non grata in the Piedmont “new Italy” and also was closely watched by Cavour and the Piedmont regime but more along the nature of house arrest.

However, it is clear that both men continued to push their agenda for full Italian unification and the elimination of Papal secular power. They continued to advocate for the forcible incorporation of the Papal States into a united Italy. Along with that they advocated the elimination of those States as a separate entity governed by the Pope as well as confiscation of much of the Papal wealth especially as it applied to large land holdings. Further Mazzini actively incited Italians within Austrian controlled Venetian territory to revolt.

Apparently part of the Mazzini/Garibaldi unity advocacy in the latter half of 1861 included organizing and rejuvenating Italian Masonic interest throughout the country. This advocacy included bringing Masonic lodges into the light and establishing the Masonic system/principles as a legitimate political resource. Garibaldi took the lead in this. He encouraged the successful opening of many official Masonic lodges, which began operating openly in all of the major cities of Italy including Rome. On December 26, 1861, 22 of these lodges met by convention organized by Garibaldi in Naples.

Ostensibly the convention was to unify the lodges under a Grand Lodge format. Toward that end the convention declared Costantino Nigra Grand Master and Garibaldi honorary Past Grand Master. Garibaldi was obviously well respected and had long been openly a Mason. So taken alone bringing Freemasonry into the mainstream does not seem a surprise. But the fact that this gathering was orchestrated to occur in southern Italy was not by accident. It should also be noted that at the convention the Palermo Masonic Lodge which had representatives in attendance elected Garibaldi Grand Master of their specific Sicilian Lodge. Interesting in that Garibaldi was from northern Italy and resided on the island of Caprera which is nowhere near Sicily. Both Garibaldi and Mazzini were always acting strategically and with the long view in their sites so you should not take this seemingly “honorary” appointment to a “Sicilian” Masonic Lodge as just gesture rather than purposeful.

I need to point this out that this “convention” of people with strong republican leanings is happening at precisely the time that Piedmont has upped its military presence to suppress brigands in the south to 60,000 troops. So far in the web history I have interrupted the military buildup as it applied to thwarting the perceived pro-Bourbon insurrections. Garibaldi however may not have viewed the buildup as a vehicle of suppression but rather on of opportunity to advance his underlying unification goals. In other words he may have viewed it as an opportunity to access a sizeable military force to further advance Masonic and unification opportunities against the Papal States. Whatever Garibaldi’s perception this “Masonic convention” may have just as likely appeared to the Piedmont regime as representing a potential second front of counter reaction to Piedmont’s control since Masons and in particular Mazzini were viewed as anti-monarchists.

This bring me to another example of how Vito’s life and movements seem to be timed toward certain events. Vito left San Fele in December, a young man from a middle-class background, who would have been from the class most associated with Carbonari/Masonic leanings. In that month he went to Naples at precisely the time that the Masonic “convention” was occurring and then subsequently later that month or early January left for America. Although I do not recall any family discussions about Vito in terms of attending or being involved in the 1861 convention it is a curiosity that the event coincides with his departure schedule. It is also a fact that events in the south after the convention take yet another violent political turn. That turn in fact again had a disproportionately negative impact on conditions in Lucania.

While I do not know if Vito had some connection to the “convention” once in America, he as well as Carlo Sisti did not stay in New York but instead headed for New Jersey and Trenton. A city where there were virtually no fellow Italians at that time, and which had a population of only about 20,000.

Trenton and Masonic History in America

When discussing Masonic history in America, Trenton has an interesting and deeply rooted place in that story. Trenton In colonial times was literally Trent’s town. Founded in 1679 at the headwaters of the falls on the Delaware, Trenton is the northwestern most point on the Delaware River to which ocean travelling vessels can sail and dock. Throughout the colonial period Trenton had a very modest population. At the time of the American Revolution for instance the population was around 5,000 people. Even by 1862 Trenton’s population was only between 16,000 and 22,000 people. Its manufacturing base, for which it would become known later, was in its infancy. In the mid-19th century Trenton was not a major center politically or economically but its geographic location created opportunity as a crossroads of east coast America. So while it may seem that Trenton was unlikely place to find a major Masonic connection, Trenton’s history is actually interesting and surprising in that regard.

According to the publication “A History of Trenton 1679-1929” published in 1929 on the occasion of Trenton’s 250th anniversary it did in fact have a unique place in American Masonic history. According to that history, in 1730 Masons then residing in the colonies of New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania petitioned the Grand Lodge of England for the establishment of a Grand Lodge in the colonies. Permission was granted that same year and Daniel Coxe of Trenton was appointed as the first Grand Master. So reference to Trenton shows up in the American Masonic story at its very inception.

According to the history, Masonic documents in England list Mr. Coxe as not only the first Masonic Grand Master in the colonies but the first in North America. He is also generally regarded as the first in all of the Americas. So it can be said that Trenton was in fact the “initial center” of Masonic affiliation in the Americas. Daniel Coxe is an interesting figure in that his father, Dr. Daniel Coxe, was personal physician to King Charles II of England. Dr. Coxe was also, through his close association with the royal family one of the original Proprietors of West Jersey. In other words one of the members of the great “land grant” which parceled out early colonial America. As such he belonged to a group of English elites that essentially owned and controlled the western half of what is now New Jersey. You would have to regard Mr. Coxe as a very important and well-connected early colonist.

After this first appointment Masonic lodges grew in number and influence and spread throughout the colonies. The first Grand Lodge established specifically in New Jersey, after east and west Jersey merged in the 1770’s, was organized in a meeting held in New Brunswick in 1786. The first Grand Master for New Jersey was N.J. Chief Justice David Brearley another Trentonian.

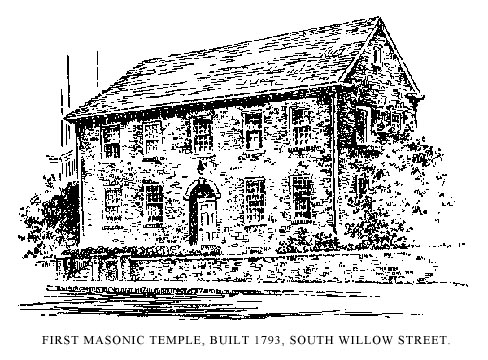

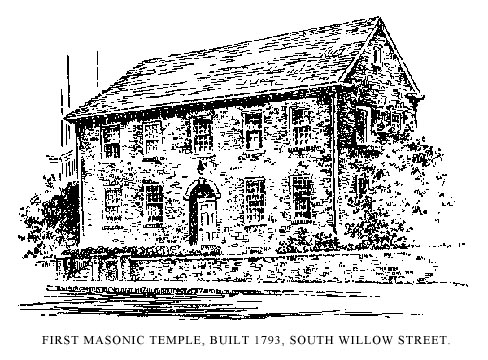

The first Masonic Lodge in Trenton was formed in 1787 a year later and Grand Master Brearley was a member of that Trenton lodge. Masons built their first Lodge building in Trenton in 1791 on south Willow Street. This lodge was referred to as Lodge # 5. The original building still exists although thru the centuries it has moved around a bit and been repurposed on occasion. Trenton’s second Lodge was formed in 1858 from an expansion of members of the first lodge. My understanding is that for many years several of Trenton’s early first Masonic lodges met at the same south Willow St. building. The second lodge is referred to as Lodge # 50. As Masonic membership and the city grew a number of Masonic Lodges would be formed in Trenton thereafter. For our purposes however when Vito arrived in Trenton there would have been only two active Masonic Lodges both meeting at the same s. Willow St. location.

Drawing of Trenton’s First Masonic Lodge Building

So even from the brief description above, it can be seen that Masonic roots in Trenton go all the way back to not only colonial times but to the very original “owners’ of West Jersey. Trenton being home to the first of America’s Grand Masters. By the time the 1860’s came along Masonic membership was growing in the New Jersey State’s Capitol and included many of the most prominent men of the day. So connecting to the Masonic organization here was a positive socially, politically and probably from a business perspective. If Vito was an Italian Mason, Trenton may very well have been a location that he would be directed to.

Garibaldi and Mazzini’s activities in Italy were well known to American Masons. First because both men were well known as Italian Masons. Second because their political objectives in Italy and beyond were based on “republicanism”, Italian unity, and the abolishment of Papal civil authority. These were causes for which there was fundamental support among Mason’s in general and American Mason’s in particular. As a result American Masonic groups actively campaigned and raised money to help support Garibaldi and Mazzini’s efforts in Italy both for the 1860 campaign against the Bourbons and Garibaldi’s “Roma o Morte” campaign in 1862. In fact English and American Masonic support also came into play in rescuing Garibaldi and Mazzini from the aftermath of the failed 1862 campaign.

There also were several prominent Italians, ex-patriots who had supported Mazzini’s 1848 republican revolt living in the tri-State area in the 1850-1860’s as well. Many were themselves prominent in the greater New York society of the day as mentioned in some previous articles. Many were secretly Italian Masons and part of the immigration that American officials refer to as the 1848 ers. It would not be too difficult to conceive that a young pro-republican Italian venturing to the U.S. would seek out such contact in order to secure job and support. You see that kind of social contact in the De Rudio story as he was a staff officer in Garibaldi’s force in 1848. From the San Felese perspective the question is there anything to suggest that Vito Frascella and Carlo Sisti were secretly Italian Masons?

I have no idea whether Carlo was but as to Vito, our family oral history says, yes. Although following the Italian tradition of absolute secrecy that is not confirmed in any writing I have located. So my belief is based primarily on oral history. Again in the oral family tradition even going back to my youth a half century after Vito’s death his membership in the Masons in Italy was always regarded as a secret that was not to be disclosed. In the telling of this part of Vito’s story older family members recited that in the past there had been occasions were inquiries were made regarding any knowledge of a Peter Frascella being a Mason. We were instructed that if we encountered such an inquiry the correct and truthful reply was that we were unaware of any Peter Frascella that had ever been a Mason. Of course we were under no obligation to volunteer that Vito used the ‘anglicized” first name “Pete/Peter” when dealing with his life in the American community.

Of course growing up in the U.S. and hearing the story in the 1970’s I had no idea what all the concern would have been about. I did not understand political suppression or risks to extended family abroad as a result of someone’s political views. I certainly didn’t understand what could be dangerous about having political views that supported democracy or a republican form of government. Clearly however even my grandfather’s generation had some sense that personal harm could come from the discovery of these types of views for family in Italy. So the secret was kept, and secret became just a part of family oral traditions for generations until this writing.

Vito’s name appears on no Masonic membership list in Italy as none exist, and his name appears on no membership lists here that I was able to find. He did not publicly enter any lodge here as he concerns that his presence or attendance could be relayed back to Italy. His Masonic connection would pretty much identify him as a Mazzinian type republican in Italy which as we will see in future articles was not good thing in Italy all the way thru to the 1950’s.

What I have found interesting in my family research is that only one personal artifact that belonged to Vito survived and was passed down thru the next five generations it took to get to me. A Masonic Penny issued by the Trenton Lodge No. 5 and dated 1858.

Masonic Penny 1858-Front

Masonic Penny 1858-Back

The coin appears to have been minted around the time of the opening of the second Trenton Lodge although it does not reference Lodge No. 50. The mint date would have been about three years before Vito arrived in Trenton and probably the coin was in circulation among Trenton Masons at the time. I suspect that he may have used it as some sort of identifier but I don’t know that for a fact. It is interesting that the family held on to the coin for so long. In terms of monetary value the coin has no significance so keeping it for so long confirms it held some other kind of strong significance to his descendants.

© San Felese Society of New Jersey