A Book of Passage

By: Tom Frascella January 2017

There were 4.5 million Italians, 80% southern Italians, who immigrated to the U.S. between 1850 and 1930. They were part of a larger exodus of Italians estimated to be 12 million, 80% southern Italian, who left Italy for foreign destinations during that same time period. These 12 million immigrants have sometimes been called “Birds of Passage” by those writing about the largest, single geographic source, voluntary, immigration in recorded human history. I have borrowed from this name in the title of this article. The reason for this is that, as previously written San Felese authorities began recording the names and often the family relationships of those townspeople who left from the latter part of 1862 onward. This created a local version of a San Fele book of passage produced for their own municipal needs. Thanks to the research by Prof. Stia of San Fele some of the recorded names from selected years are available to us and have been reprinted on this website in earlier articles. These lists represent a valuable resource in reconstructing the impacts of historical events and the solutions our ancestors developed in response to the great civil unrest of mid-19th century southern Italy.

The list for the years provided together with future research may also someday provide us with a comprehensive and fuller history of the migration of San Felese. Prof. Stia’s research has, by providing the first list from 1862 confirmed in verifiable detail the early exit date from the barony of San Fele to the U.S. and South America.

Looking at U.S. census numbers for Italian immigration to the U.S. the official numbers registered by the U.S. government estimate immigration from Italy at approximately 10,000 between 1850 and 1860, and only an additional 22,000 for all of the 1860-1870 period. If these U.S. census numbers are close to correct the implication of these statistics is that our ancestors when arriving in 1862 were among the first 10,000 -12,000 immigrants to the U.S from Italy. A very early part of this mass exodus of Southern Italians. They were arriving at the very start of this extraordinary 4.5 million person migration to the U.S. and 12 million person Italian migration worldwide. I should also repeat that U.S. customs viewed the earliest of these immigrants, 1850-1880, as part of what the U.S. labelled as 1848 or 48 ers. In other words those fleeing the suppression from failed European republican revolts of the era. Therefore as a group regardless of the western European nation they were arriving from the 1848 ers were considered “political refugees”.

The fact that so many of our southern Italian ancestors were leaving San Fele and Lucania at this time is also interesting in that historically approximately 90% of Italian immigrants of the 1850-1880 time slot were considered in American histories as originating from northern or central Italy. The fact that a group of “southern” Italian immigrants were arriving from a rural and fairly isolated mountainous small towns of Basilicata is an unprecedented and not well discussed chapter in Italian-American histories. This “new” fact therefore is an event that deserves careful examination both for its micro importance for the region and for its significance in the larger Italian American immigration story. These men and women were seeking refuge from the strife directly connected with unification and its immediate implementation and aftermath.

Strife: The State of the Insurgency in the Vulture Region in Late 1862

Since the December 1861 departure, capture and execution of Bourbon commissioned and supported General Borjes the remaining insurgent bands in Basilicata and the rest of the southern Italian mainland appeared content to mount only small scale confrontations against Piedmont. The insurgents faced with the ever increasing numbers of Piedmont troops assigned to the rural areas recognized that large scale assault was impractical.

The arrival of Garibaldi and his men for the ill-fated Roma O Morte campaign in August 1862 was independent of and unassociated with the general causes and actions of insurgency in the rural south. When Garibaldi and his men were stopped in Calabria local insurgent groups were not participants on the battlefield at Aspromonte. As a result Garibaldi’s capture did not play a direct role in the conduct of hostilities in Basilicata. However, even as late as August of 1862 Basilicata and in particular the Vulture region still presented a volatile mix of political and armed civilian factions. These factions presented for the Piedmont regime and the Piedmont supported local authorities a serious concern and treat to stability.

My use above the term Vulture or the Vulture region of Italy is meant to describe the area within roughly a twenty mile radius of San Fele. Mt. Vulture is a large extinct volcano that dominates the landscape in the area of San Fele. Generally the Vulture region is composed of the towns that are close enough that the Mountain can be viewed from within their confines. The 2,000 insurgents loosely under the command of Carmine Crocco had divided up into smaller bands throughout the Vulture for the winter thru summer of 1862. They survived at first, on the assistance of the locals who supported them with supplies either voluntarily or through intimidation.

Crocco himself came from the Rionero area of the Vulture and had since the beginning of the insurgency enjoyed the secret support of pro-Bourbon Giustino Fortunato and several other local elite families. Crocco and his men often received supplies and safe haven on the estates of the Fortunato family. On August 22, 1862 as Garibaldi was preparing for his landing on the southern mainland Giustino Fortunato died of natural causes. Upon Fortunato’s death not only did Crocco’s insurgency bands lose a major benefactor, they lost its principle advocate with the Bourbon Monarchy. Giustino Fortunato was a relative of the Bourbon King as well as the former regime’s Prime Minister between 1849 and 1852. His death created a vacuum between the Vulture insurgents under Crocco and the Bourbon cause. Without Fortunato’s considerable political connections lesser landed nobles of the Bourbon regime were less willing to risk Piedmont retribution for suspected aiding of the insurgency.

This decline in elite familial based support was critical to the grass roots insurgency’s direction. Crocco by his personal history was not a natural Bourbon supporter but he seemed willing to go along and to trust Bourbon intent as long as Fortunato favored it. Without Giustino’s presence there was inherent distrust between the insurgents and the remaining elite families, including the Fortunato family. This distrust was based on the insurgents’ experience during the 1861 campaign in Potenza. Other former elites of the Bourbon regime had initially supported the Borjes’ campaign in the region, but defected under pressure from the Piedmont military. So as the fall of 1862 approached the Vulture insurgents found themselves more isolated and less supported in their cause than at any time previously. While subtle, this single loss of Giustino Fortunato changed enough of the relationships between the factions to have a significant impact on how the insurgents operated and how the locals reacted to them.

To this set back was added the Piedmont declaration of an emergency “State of Siege” in the south. As previously stated the State of Siege was originally imposed as a result of the way Piedmont felt it needed to deal with Garibaldi’s campaign while he was still in Sicily. Piedmont feared Garibaldi’s ability to raise a sizeable force among southern Italians as he had done once before. Garibaldi was largely viewed as a hero, liberator and comrade among southern Italians. He was also free from the grievances the southern population had against Piedmont as he had been removed from command in October 1860 and was not a part of the suppressive acts of the regime in the interim. In fact, while the grievances and other offensive acts were being committed by the Piedmont regime in the south Garibaldi was something of an out of favor non-entity exiled on his island. The State of Siege declaration gave the Piedmont military in the south the “temporary” ability to suspend civil liberties in favor of martial law. This was originally meant to be a powerful coercive weapon in separating Garibaldi from any civilian support.

With the quick collapse and capture of Garibaldi and his forces on August 29th essentially without a fight, the technical emergency upon which the declaration arose was as a practical matter eliminated. However, General Cialdini with the silent acquiescence of the Piedmont regime continued the imposition of the declaration applying it to the rural south and Sicily. Not only did he continue apply this unconstitutional application of military force on civilian populations, but he applied it selectively to various regional rural populations in the south. Especially, in those regions where insurgency was at its’ strongest like the Vulture.

I should point out that the State of Siege declaration did not apply to urban Napoli the largest population center in the southern mainland. This is because the Piedmont regime had allied itself with various elements of organized crime, the Camorra in Naples, in order to effectively suppress civilian opposition. In 19th century southern Italy the Camorra’s reach and influence was largely limited to Campania and specifically coastal urban Campania. Places like 19th century Basilicata were too impoverished and culturally uninfluenced by Camorra based politics and violence. In fact Italian criminal experts assert that organized crime did not infiltrate the cultural/political norms of Basilicata until 1980. Even then it was an imported attempt by the Camorra to siphon off federal and relief money from the areas devastated by the 1980 earthquake.

When the Borjes campaign of December 1861 fell apart the Piedmont military had originally expected the insurgents who had divided up in the mountains to basically weaken and dissolve. They thought that the harsh winter would break their resolve and decimate their numbers. Instead Piedmont found out too late that the insurgents had been able to quickly obtain the supplies from local farmers, whether voluntarily or not, and to build and maintain the shelter they needed to not only survive but thrive in the mountains.

In 1861 General Cialdini did not have enough manpower in the south, about 60,000 to 70,000 men to effectively stop the food and supply raids of the insurgents. As the fall and winter approached in 1862 Piedmont had increased its force to a force which numbered 80,000-90,000 men. This meant that Cialdini and his commanders could more effectively attempt to interfere with insurgent resupply. The problem was that it was still a difficult task and one made more difficult by the fact the local insurgents had significant support and connections among the locals. Piedmont had done little in the first years after unification to attempt to win the hearts and minds of the southern Italian rural lower and middle-class.

General Cialdini and Piedmont had the choice of several ways to attempt to interfere with the continued resupply of the insurgents by locals for the upcoming 1862 winter. They could confiscate supplies before the insurgents confiscated them from the local farmers and communities. Given the extensive authority of martial law there was no legal impediment to doing this however such a move would be very unpopular. With 90,000 men in place and armed with the power of martial law “State of Siege” authority, Cialdini chose to begin implementation of the strictest of suppression tools at his disposal.

Basically he implemented a directive that anyone accused of aiding or abetting the insurgents was subject to arrest and/or execution. So starting in September 1862 the Piedmont military stationed or deployed in southern rural Italy began to exercise extreme measures against the civilian population especially in Basilicata in order to discourage support for the insurgents. To make clear what this meant under the State of Siege declaration was you did not even have to actively participate in the armed rebellion. The accusation of aiding and abetting the furtherance of the insurgents was enough to share in the “punishments” associated with the revolt. I must also stress General Cialdini was not an individual who showed concern or likely to differentiate as to whether a civilian’s aiding or abetting was voluntary or forced by the insurgents. So “alleged” complicity became the “offense” under the State of Siege declaration as it was applied.

I chose to use the words “offense” and “punishment” rather than crime and penalty for a very important reason, there was no adjudication of the allegation merely a summary finding of offense and random application of punishment to those so accused.

Complicit

According to the Merriam-Webster definition of the word complicit it means “helping to commit a crime or do wrong in some way”. As we have discussed at length in previous articles there was great civil unrest in southern Italy especially in Basilicata in 1861 and 1862. Regardless of the nature of the unrest or the political or civil faction of origin, in combination, the unrest threatened the authority of the Piedmont regime and was therefore not differentiated for purposes of punishment by Piedmont authorities. Civil disobedience was an offense for which you were labelled a briganti regardless of the nature of your grievance. Therefore “criminality” attached to acts that were otherwise not criminal in nature especially those that were actually politically based.

Early on in the insurgency the labelling of the insurgents as briganti/brigand-outlaw was problematic for many politicians in Italy but not for the reasons that would be commonly thought. The commission or allegation of a crime/criminality suggests a need for civil adjudication/trial in a civil court under the constitution of Italy. The imposition of the constitutionally unauthorized martial law/ State of Siege in response to Garibaldi’s campaign in August 1862 made criminals out of what was essentially political action. It also allowed incarceration even execution without trial. Because martial law was recognized to be a valuable tool for those charged with restoring Piedmont authority against a rising tide of civil unrest a way around the pesky need for due process had to be found. A way to differentiate between the southern briganti and those criminals/briganti in the rest of Italy who were entitled to trial. A discourse quickly began to develop in Italy between the more liberal members of the Italian Parliament and those more regime based regarding whether those accused of rebellious acts must be afforded a trial and proofs of guilt if their acts were “criminal” or briganti in nature. The Regime realized that this debate had to be resolved in a way most advantageous to the authority of the State.

As we will see in the next article the question of how to extend the power of the State and denial of civil rights universally to the rural southern population was resolved by means that haunt the social order of Italy to this day. It may seem unimaginable that any “civilized” mid-19th century European country would eliminate all civil rights and impose an authoritarian order on any part of its citizenship. However, it would be proposed that thru unsubstantiated pre-judgment a geographic class of people could be labelled criminal and punished accordingly. Equally unimaginable is that criminal status could be applied to families and children of those accused of being briganti. As that is precisely what began to occur to the people of certain parts of the south in the September-October 1862 time frame it is not surprising that people began to flee. Among those people, the people of Lucania including those of San Fele.

The First Entry in the San Fele Book of Passage

According to Prof. Stia’s research as included in his book on San Fele “San Fele Seconda meta dell Ottocento La Grande Emigrazione” in October and December of 1862, 35 residents of San Fele left the town immigrating to the Americas. These individuals left with an unexplained required permission of the Mayor of the town, Raffaela Spera, according to Prof. Stia’s notes and text. To my knowledge permission of the local town authority to leave to go abroad had never been required before this point in time. This suggests that a new order of control had been imposed upon the villagers. I believe that recording departures to overseas destinations at the very least insured that those leaving were not labelled briganti or suspected as joining the insurgents. This was important in a climate where the mere accusation of joining the insurgents could result in the punishment of family left behind.

Of interest to us Professor Stia clearly understands and identifies these thirty-five people as the beginning of the devastating exodus from the town that would follow over the next several decades. In 1862 San Fele was a town with a population of approximately 10,000 people.

According to Prof. Stia’s research and the documents recorded these thirty-five individuals were heading to three separate ports in the Americas, New York U.S.A., Montevideo, Uruguay, and one individual to Buenos Aires Argentina. The list of those who were going to the U.S.A. is as follows:

Caputi Vincenzo, with his wife Angela Girardi and their children Vincenzo and Mariantonia Oct. 30

Frascella Gaetano Oct 30

Giallella Lonardo Oct 30

Girardi Francesco, with his wife Filomena Marrafino Oct 30

Girardi Lucrezia, with her children Francesco and Margherita Oct 30

Russo Michelangelo, with his wife Caterina Ticchio and child Mariangela Oct 30

Giallella Vito and sibling Sofia Lucia Giallella Oct 30

Tomasulo Francesco, with his wife Theodora De Vito and son Donato Oct 30

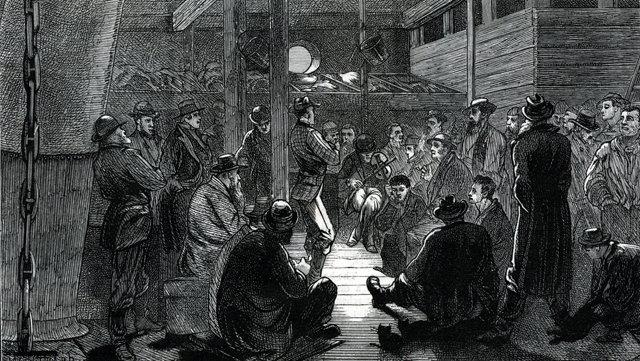

By my count of the above there are 19 individuals heading to New York in October 1862. It is my understanding that the journey back then to the U.S. took between 48 and 60 days of travel. Again the trip was most likely by sail powered craft in 1862 and would likely make several European stops. It was also likely an older poorly conditioned vessel, which was also part cargo ship was the type of vessel most available. These were not luxury liners. I cannot imagine what traveling the north Atlantic in late fall early winter on a small wooden sailing ship, unheated and in close shared quarters for a month and a half was like. The drawing below may give some indication of what such a vessel in High cold seas would have experienced.

Drawing of ship making the difficult fall winter crossing in the north Atlantic.

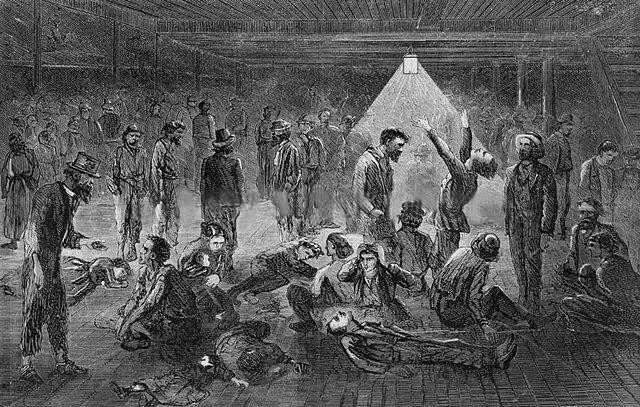

In looking at the above immigration list what I find interesting is that these people are leaving as a group, all together at the same time. In addition most of them are leaving as intact family units. This would seem to argue against the movement being casual, or spontaneous or for that matter strictly adults seeking job opportunities abroad. While Italy has a long history of exporting skilled labor it is not usual to see an intact family leaving for temporary work. Also given that conditions aboard these types of transit vessels they were transiting on what was at best a primitive risky passenger craft. At the very least these people were risking their health, safety and the comfort of the entire family. As can be seen in the drawing of the passenger hold of such a ship of this era, the passenger below quarters on these ships were barely habitable. So again, this was not a journey to be under-taken lightly. I am sure only the most desperate of circumstances would have caused this type of “voluntary” choice.

Drawing of passenger quarters as Immigrants of the era might have expected.

One other problems that these individuals faced was that coming from a relatively isolated mountain community it limited their exposure to foreign diseases. Once boarding these ships they became exposed to illnesses that they would have little immunity for. Housed for the voyage in the fashion depicted passengers were frequently exposed to disease and illnesses associated with the cramped quarters, unsanitary conditions, cold and violent tossing about that was common. Of note, when passengers became ill there were no medical resources available.

Drawing of treatment aboard a craft where illness had broken out.

Prof. Stia points out in his work that these individuals heading for the United States are aware that the U.S. is engaged in a bloody civil war at the time of their departure. Obviously they are prepared to go anyway. This as opposed to going to South America which was an option that was also available. South America would seem to be the more logical choice although these individuals did not choose it. I say this as I would think that immigrating to a foreign country where the religion, language and culture were close to one’s own would make survival easier. The immigrants choosing to go to the U.S. because of the cultural and language problems they knew they would encounter, I would suspect, must have had some expected support opportunity in place in the U.S. Otherwise to be simply dumped on foreign shores in the dead of winter in a country at civil war would have made survival difficult.

From my own family history I know that at least one of these passengers, Gaetano Frascella, who was travelling alone, was planning to meet up with his older brother in the U.S., my great-great grandfather Vito. I know that when he arrived in the U.S. he joined his brother Vito and Carlo Sisti another early arrival who were both employed by a masonry contractor from Trento doing military construction, fortifications work, in and around Washington D.C. When the Civil War started there were approximately 12 forts/fortifications in the Washington area. In the early years of the war Washington. D.C. was under constant threat from Confederate forces. This threat made it necessary for a Union army build-up to protect the Capital from capture necessary and an emergency project. During the four years 1861-1865 the number of fortifications and artillery emplacements protecting the Washington D.C. area rose from 12 to 84. This created work opportunities for masonry labor during the course of the war. While I can confirm only that at least three San Felese were so employed, Carlo, Vito and Gaetano, it is likely others from the group shared the work opportunity as well.

As an aside in the family stories passed down to me it was said that despite the strenuous work and some language barrier involved my ancestor, Vito, made it a point to attend and listen to President Lincoln’s speeches whenever his work scheduled permitted. He was quite impressed by Lincoln and not only proudly became a Republican when he fully immigrated to the U.S. but insisted his children and grandchildren belong to the party of Lincoln.

From what I gather from my translation from the page of Prof. Stia’s book which contains this entry on immigration, Professor Stia considers this the beginning of the mass immigration, not exile or asylum seeking. One reason for this is that of the thirty-five people listed only two returned to resume their residency in the town of San Fele. So this was a one way trip for almost all of these folks

Unlike those leaving San Fele for the U.S. who all left on October 30th, those leaving for Montvideo left in two groups, the first October 26th and the second December 6th. Since a number of the readers of this site either have relatives in Uruguay or actually are in Uruguay I will include those names in this article as well;

Di Gianni Nicola Maria di Vito Vincenzo Oct. 26

Di Lorenzo, Lorenzo di Pietrantonio

Di Lorenzo, Michele di Pasquale

Fabbrizio, Gaetano di Francesco

La Rossa, Maria di Pasquale

Lorenzo, Antonio di Pasquale e moglie-Giulia Mare

Lorenzo, Giuseppe, di Pasquale

Pierri, Marco fu Francesco

On December 6th the remaining group that left for Uruguay were;

Caputi, Vincenzo di Pietro

Faggella, Vincenzo di Gabriele

PIETROPINTO, Vincenzo di Francesco

I should point out that the one individual headed for Buenos Aires also left on October 26th

Abarno, Giovanni fu Francesco.

I think that as the next several articles get published on our website a clearer picture of just what was beginning to happen in Italy that was causing the migration in Basilicata will emerge.

© San Felese Society of New Jersey