PETER COOPER (1791-1883) FOUNDER

COOPER-HEWITT TRENTON IRON WORKS

BY: TOM FRASCELLA SEPTEMBER 2014

At its apex Trenton’s three major Steel Manufacturing factories, John A. Roebling & Sons, American Bridge and U.S. Steel were massive complexes employing over ten thousand workers. These complexes were located primarily in Trenton’s south and east Wards. From the beginning much of the work force at these factories was made up of immigrant labor, first Irish and German and then southern and eastern Europeans. At first these factories were built on land was on the outskirts of the City. Then as the factories grew and the worker housing grew the areas became a part of the City of Trenton proper. The Borough of Lamberton became South Trenton in 1851 and the Borough of Chambersburg became the Chambersburg section of Trenton’s east ward in 1888.

The first of these manufacturing giants to locate in Trenton was the Trenton Iron Works also known as the Cooper-Hewitt Iron Works. Eventually through corporate growth the Cooper-Hewitt works would become part of the American Bridge Co.

As the first of these companies to locate in Trenton arriving in 1847 the Cooper-Hewitt Iron Works played a major role in the development of Trenton as an industrial center. The founder and force behind the company was a fellow named Peter Cooper. Today he is known primarily for the legacy of his Philanthropic work but it is his early industrial innovations that are the focus in this article.

Without Cooper’s decision to locate his iron foundry on the banks of the Delaware, Trenton’s development would likely have been far different. The opportunity of work that sustained generations of immigrants and their families would not have been available and the rapid growth of Trenton from small town to city would not have occurred.

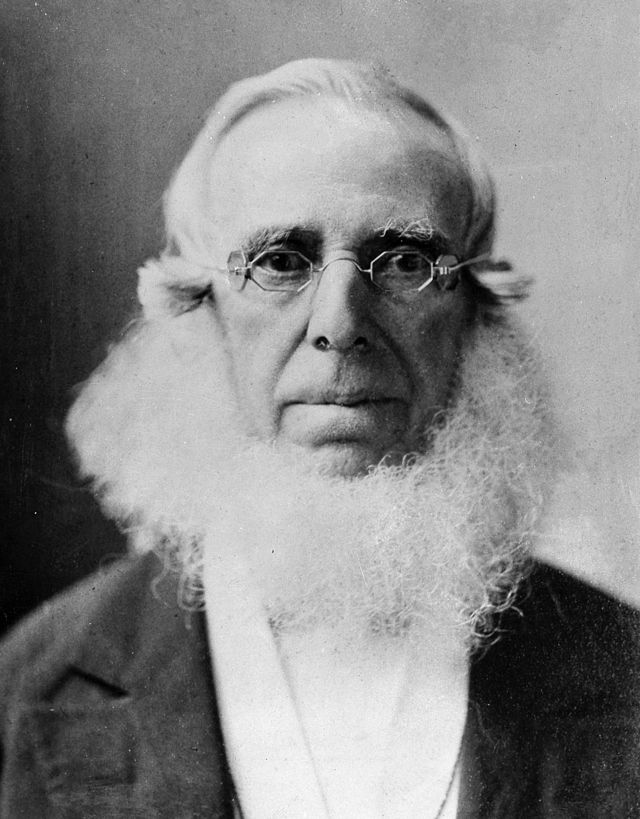

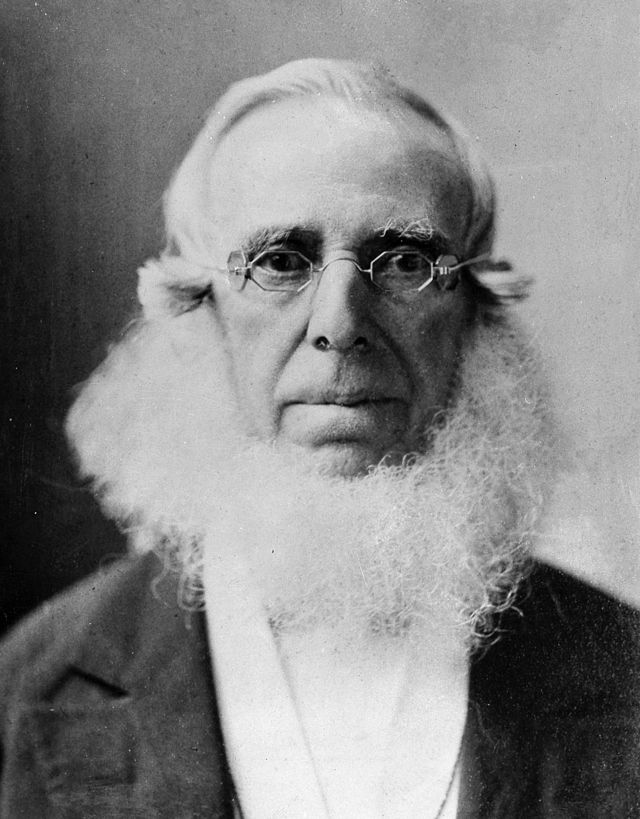

Portrait of Peter Cooper

Cooper was one of the most interesting individuals whose birth occurred just at the dawn of our new nation. His contributions in life and beyond to our young nation in politics, business, invention and social consciousness are vastly underappreciated today. Mr. Cooper was born the fifth child of John Cooper a grocer in New York City. His father and grandfather had both served in the American cause during the Revolution. His father was a kindly man who lent too much credit to customers and went bankrupt when Peter was just five years old. His father then took up a number of jobs with varying degrees of failure. He started with hat-making and Peter as a young child worked at that endeavor with him to help support the family. As a result of going to work at such an early age Peter only had one year of formal primary school education. Throughout his childhood and early teens Peter worked with his father as his father tried and failed at brewing in Peekskill, brick-making in Catskill, and again brewing in Newburgh New York. No formal education and a succession of failed occupations would hardly seem to be the profile that would lead to a great American success story. His father’s business failures however seems to have only encouraged young driven Peter toward achieving his own successes.

While success may have alluded his father, young Peter was recognized early on as an inquisitive youth, a skilled mechanical “tinkerer” and the “real” deal as an original thinker. Where his father tried and failed to fill oak barrels with ale, Peter saw a different potential use for the barrels. At the age of thirteen in 1804 he came up with his first “invention” a piston-ram, crank driven washing agitator which fit above a conventional oak barrel.

At seventeen he was able to get an apprenticeship with a carriage maker named John Woodward in New York City. Woodward quickly recognized Peter’s inventiveness and soon Peter was a paid employee as the quality of his work soon exceeded that of his teacher.

At age 20 in 1811 while still apprenticed as a carriage-maker Peter invented and demonstrated a tidal driven ferry in New York Harbor. The ferry operated on a continuous chain starting at the point of the current on Staten Island. Power to pull the chain came from air compressed solely by the energy of the tides. He demonstrated the system to the then Mayor of New York and Robert Fulton. Fulton was not impressed and the invention failed to gain financial backing as a result of Fulton’s negativity toward the method of propulsion. Of course Fulton was by this time fully and financially committed to steam propulsion. Cooper, never forgot the rejection which he felt was prejudiced by Fulton’s own agenda.

He however carried on but just as his carriage making apprenticeship concluded, Peter’s employer went bankrupt. The cause of the bankruptcy like that of his father’s early business failure was the result of customers defaulting on carriage orders. This situation was apparently too reminiscent of his father’s early failure and Peter decided that his future was not in the carriage making business. Instead, Peter got an opportunity to buy into a cloth shearing company. It is here at the age of 22 that Peter’s luck and future changed. The shearing cutter was steam driven providing the tinkerer in Peter great opportunity to start to experiment with steam driven technology. Peter bought the patent rights to the machine and began to manufacture and sell the shearing machines to American clothing manufacturers. He entered into this endeavor just at the start of the War of 1812 and just as England cut off clothing exports to the U.S. As a result clothing manufacture in the U.S. was greatly bolstered as was demand for his machines. For the duration of the War Peter did quite well and was able to marry and support a wife and soon two children.

At the end of hostilities in 1816 England flooded the American market with cheap clothing made by underpaid English child labor. The flood of cheap goods put many American clothing manufacturers out of business. Without a market Peter converted his factory to manufacturing cabinets. As always his inventiveness came to the forefront and it was during this time that Peter obtained his first patent for a wind-driven self-winding baby cradle. The mechanisms and springs that operate the cradle are basically the same as are in use in mechanical baby cradles today. During this time he also tinkered with a number of small steam engine designs. In 1818 he sold the cradle patent and invested the money in property in New York City. At this site in the City he developed a successful grocery business. It is interesting that he chose to take up in the business where his father had first met failure. Succeeding, and succeed he did, where his father had initially failed was important to Peter, the grocery business however bored him and he sold it in 1822 at a substantial profit. At this point he bought a glue making factory. Traditional cooking of the highly flammable ingredients that went into glue manufacture was very dangerous and Peter was nearly killed several times. That is of course was until he invented a double boiler steam driven system of heating the ingredients so as to avoid ingredient contact with an open flame. His method the double boiler system is still in use in the glue/food/chemical industry today.

Peter was involved in the glue business from 1820-1865 when he sold the company to son Edward. During the roughly forty-five years of his involvement he is credited with a number of innovations in the field. As a result of his advancements in glue production Peter was able to develop twelve grades of highly refined glue products. Among the products he developed commercially was the commercially practical manufacture of gelatin. He would eventually sell this patent to a cough syrup manufacturer who further developed the product as a food novelty that his wife named Jell-O. Cooper also developed tests for confirming the grades of glue and a test for glue stiffness. His research lead to the production of a number of animal fat based chemicals and oils including Neat’s Foot Oil and important substitute for whale oil. During his ownership of the glue factory, his business would become the largest glue manufacturing producer in the world. The company would make Peter Cooper a very rich man before the age of forty. However, although financial success was no longer a concern his restless spirit couldn’t stop with the successes already achieved. Many of his contemporary American industrialists where beginning to express their wealth in lavish life styles, but Peter Cooper remained very modest in dress and housing. Throughout his life wealth remained a tool to enhance achievement and progress not an opportunity for self-indulgence.

In the late 1820’s Cooper became aware that rail/ horse drawn trolley transportation was beginning to develop in and around the bustling port of Baltimore. Believing that an investment opportunity was there he bought 2,000 acres of swamp land on the outskirts of Baltimore with the intention of draining the water and selling off housing tracks. As the engineers drained the area they discovered iron ore deposits and Cooper decided to get into the iron manufacturing business. In 1828 he started the Canton Iron Works in Baltimore. As there were few rolling mills for the manufacture of rails in the U.S. he invented a process to do that. About the same time investors began to promote the building of a westward railway which would be called the Baltimore-Ohio railroad. The problem with promoting the railroad was that even the most advanced English steam engines of the time lacked sufficient power to pull loads up and around the grades anticipated for the westward routes. Cooper recognized that a fortune could be made and that the future of his iron works lay in supplying the rails for such an undertaking. What was missing for the railroad venture to succeed was a workable demonstration that steam locomotion was up to the task of delivering the needed power. The fact that no such engine existed did not bother him. He innovated and modified existing locomotive design and built a small but very powerful train engine. This was the first train engine built in the U.S. and the public dubbed it the “Tom Thumb” for its small size. The tiny engine was able to pull a car with forty passengers at a speed of ten miles an hour without any difficulty. His Canton Iron Works received orders for the rails. This allowed him to begin successful rail production initiating a second fortune through those sales. He declined to follow up on his steam engine innovations by either advancing those designs or patenting his innovations many of which became standard in locomotive design going forward. For whatever reason he appeared content to be a supplier to the industry not a principal in railroad construction.

During the 1830’s Cooper ran for and was elected to New York’s City council. It was Cooper who as a member of New York’s City Council proposed the project that brought clean upstate fresh water to the City and created the Central Park Lake as a reservoir to act as a gravity back up to the pumping system in the event of fire. Of course acquiring and delivering adequate fresh water to the City was critical to the City’s health and its potential growth.

To do his inventiveness between the years 1828 and 1847 justice would probably take several more pages than I have available here. However an example I will include here is that Robert Stevens designed but did not patent the “H” rail in 1832 for use on the Camden Amboy rail line which Robert Stevens’ family owned. This design which became the standard rail shape worldwide is believed to be the inspiration for the “I” beam which was first manufactured in cast iron in an American foundry by Cooper’s Iron Works. Copper is also credited with later bringing the Bessemer steel production process invented in England in 1855 to the U.S.

Following up on his rolling mill success in Baltimore Cooper began buying up iron ore mines in northern New Jersey. The availability of the raw material, access to the rich coal mines in Pennsylvania and the developing transportation network of the northeast convinced Cooper that Trenton New Jersey would be an ideal spot to locate a new foundry. In 1847 he built the Trenton Iron Works on the Delaware River just below the Falls of Trenton.

Photograph of the surviving Trenton Iron Works Building built on the original 1847 site

As with many of his ventures he left the day to day running of the businesses in the capable hands of his son Edward and Edward’s best friend and Edward’s sister’s husband Abram Hewitt. The Trenton Iron Works became known as the Cooper-Hewitt Iron Works. It was Peter Cooper in 1848 however that convinced John A. Roebling who needed access to rolling mill production to relocate his wire rope factory alongside of Cooper’s foundry in Trenton. In fact, Cooper also accommodated Roebling’s early endeavors by allowing use of the Sartori mansion, the Cooper-Hewitt headquarters in Trenton, for Roebling’s design work.

The task of day to day operation of the Cooper-Hewitt foundry which was initially overseen by Abram Hewitt in time fell to Abram’s brother, Charles. Charles not only ably ran the foundry but eventually became a part owner of the Trenton facility.

Peter Cooper, his son Edward Cooper and Abram Hewitt remained primarily headquartered in New York. Their accomplishments both social and financial also focused primarily in New York. Edward Cooper and Abram Hewitt both became future Mayors of New York although for different political parties.

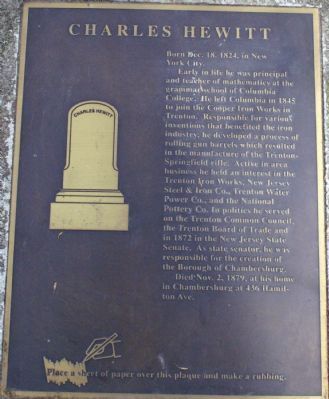

Charles Hewitt by nature of his position in charge of the foundry became the member of the family most involved in the development of Trenton. He also had an interest in politics and would eventually become a New Jersey State senator. It was Charles that sponsored the legislative Act creating the Borough of Chambersburg in 1872. He built and lived in a stately residence at 436 Hamilton Ave. in the Chambersburg section of Trenton until his death in 1879.

Photograph of 436 Hamilton Ave. as it appears today

Charles Hewitt is also known for a number of iron manufacturing innovations including an improved process for rolling gun barrels. It is this process that helped the foundry obtain Union army contracts including manufacturing a number of the Springfield rifles used during the conflict. In fact there is a sub set of the rifles that are identified as the Trenton Springfield rifles. Charles is buried in the cemetery by the Trenton train station where a memorial plaque honors his memory.

Memorial Plaque honoring Charles Hewitt

It should be noted that although family financial circumstances prevented Peter Cooper from personally obtaining formal education, he remained a life-long advocate of free public education for both children and adults. For a time he was head of the New York City Public School Society which ran New York City’s public schools. He spearheaded the introduction of evening classes in 1848. Of course he financed the concept of an adult free advanced technical school which became a reality in the form of the Cooper Union started in 1853. Tuition to Cooper Union was free to all of its students until 2014. Much of the school’s budget is funded by rent on the land that Cooper bought for his grocery business in Manhattan.

On the social front Cooper was an early anti-slavery advocate and during the Civil War advocated for the enlistment of former slaves in the Union army. He was also pro-Indian rights and paid for many Indian delegations to Washington in order to put a face on their advocacy. His lobbying efforts were responsible for the creation of the Board of Indian Commissioners during the Grant Presidency.

In the 1850’s Cooper was among the original five men who formed the New York and London Telegraph Company and in 1855 the American Telegraph Company. In 1858 he supervised the laying of the first Trans-Atlantic telegraph cable. At the time of the Civil War Cooper’s telegraph companies handled 80% of all U.S. telegraph traffic.

In addition to his philanthropy in funding various causes and the Cooper Union, he also founded the New York Gallery of Fine Arts in 1845, the New York Sanitary Association and the New York Asylum for Delinquents in 1851. The later of these institutions will come back into this site in future articles.

© San Felese Society of New Jersey