CELEBRATION OF THE MADONNA DI PIERNO FEAST

BY TOM FRASCELLA AUGUST 21, 2011

As we have previously written the feast of the MaDonna Di Pierno has been celebrated in the village of San Fele, region of Lucania, Italy since the year 1139 AD. The celebration of the feast day takes place traditionally on the Sunday following the feast of the Assumption of Mary. This date is shared with one of the regions other notable “healing saints” St. Rocco. As the region has suffered many great plagues through the centuries devotion to Mary, San Rocco and San Dinato among others has been and is an important part of the religious culture of the region.

Lucania is the ancient name of the region of Italy that roughly coincides with the modern Southern Italian State of Basilicata. The people of the region customarily refer to themselves as Lucani or specifically by village such as San Felesi for those who come from San Fele.

The Lucani began immigrating to the United States in significant numbers starting in 1856. After centuries of political upheaval and poor economic development the major catalyst for the immigration was a massive earthquake which leveled the region’s only major city, Potenza and many of the surrounding villages and towns. Many of the immigrants arrived with little more than hope, the clothes on the backs and their faith. Circumstances forced these new arrivals to seek out the cheapest an often most substandard housing available. In the port city of New York the poorest and worst of these early American slums was known as the “Five Points” section of Manhattan.

The conditions in which they lived exposed them to many serious health related issues including TB and other epidemics. The area had the worst health related adult and infant mortality rate in the nation in the later part of the 19th century. The Lucani tried to transfer their religious customs especially their devotion to their “healing saints” to their new environment. However, American religious customs did not include the Italian “festa” tradition. The early Italian immigrant attempts to hold such devotions were largely rebuffed even within the Catholic Church in America. Undaunted the Italians began setting up small temporary private shrines on their Saints’ Day on the only property available to them, the garbage filled rat infested back alleys of the “Five Points”. This type of activity further made them seem foreign and bizarre to their neighbors.

The Five Points area of New York serves as a good example of what early Italian immigration was like and the hardships those immigrants faced. In 1855 only 2% of the population of the Five Points was Italian. By 1880, with Italian immigration surging, 23% of the community was Italian. These statistics reflect in part that 4,000 Italians immigrated to the US from 1855-1860, 16,000 from 1860-1870, and 60,000 from 1870-1880. 25%- 30% of those immigrating during this period were from Lucania. In 1880 the Italian immigrants of the Five Points began lobbying the Vatican to send Italian priests and nuns who would better understand and respect their religious customs. The period 1880-1890 saw 170,000 Italians immigrate to the US and the Italian population of the Five Points rose accordingly to 49% of the community.

Although the Bishop of New York did not support the request for the presence of “Italian” clergy servicing the immigrant community Pope Leo XIII did. Starting 1885 preparations were made to send the Scalabrini priests and nuns, so-called because Italian Bishop Scalabrini headed the operation, to New York. By 1888 the priests and nuns, including a young Italian nun named Sister Francesca Cabrini had established the first Italian National Church in the United States, St. Joachim, in the Five Points neighborhood. The Bishop of New York thereafter specifically instructed the Scalabrini clergy that they were banned from holding any public religious procession or festa. On August 16, 1888 under the organization of an umbrella group the “Potenza Society”, the first Italian “festa”, the San Rocco festival, processed from St. Joachim’s Church. The various Lucani villages were represented in this procession and each brought banners depicting their patron saints, the Ma Donna Di Pierno from the village of San Fele being among them.

St. Joachim’s Church in the Five Points, now known as New York’s “Little Italy” was demolished in the 1960’s to make way for urban renewal. However the San Rocco feast continues to be celebrated from St. Joseph’s Church in the same neighborhood. This year marks the 123rd annual procession. The San Felesi/ Lucani community of Trenton would trek up to New York to participate in the Di Pierno feast until the early 1900’s when their own St. Joachim’s Church, an Italian “National” Church, was built. From that point on the Trenton community observed the Ma Donna Di Pierno feast day locally.

With the above as background, I thought it might be informative for the community to include some early descriptions and photographs which relate to the above.

The first description of the “Festa” presented is from an Italian language novel written in 1893 and translated the title is “The Mysteries of Mulberry Street”.

“Mulberry Street was on holiday: from the windows of the Italian houses hang tapestries, flags, and three-coloured lantern, and everywhere were garlands of light-bulbs…In the street, the crowd was happy and noisy: women-and among them several were very young and handsome-wore their holiday dresses and brought the gay note of gaudy colours amid the dark suits of the men and the uniforms of the military societies. San Rocco was being celebrated, and the Italians of Mulberry Street wanted to do things properly. Towards 11 a.m., the call of the trumpets was heard and in the distance flags and banners appeared. The crowd thronged the sidewalks to enjoy the parade in honor of san Rocco. A squad of policemen headed the procession, followed by the Conterno Band, and right after by a banner on which San Rocco was painted in oil, with all his wounds and his dog. Two flags, one Italian, the other American, flapped at the banner’s sides, thus placing the saint under double protection. Then came the members of the Societa of san Rocco, stern and proud in their blue dresses with golden buttons and stripes, as if the whole world belonged to them. In the buttonhole of their parade dresses, they had flowers, ribbons, and cockades. After another musical band, a military society paraded, in uniform of the military engineer corps, with the three colours flapping in the wind; and then came the colossal banner of San Rocco, wounded more than ever, and after it the (societies) of the Carmine, of the Ma Donna Addolorata, and of other saints like San Cono, Sant’ Antonio, etc”

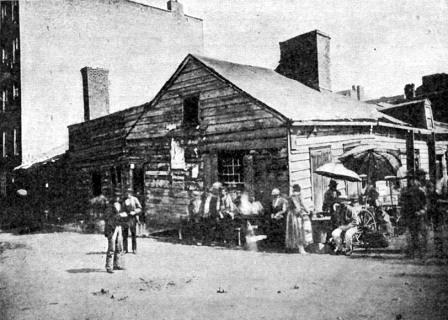

Photo From “How the Other Half Lives” by John Riis “The Bend” Mulberry Street

The following New York Times article from August 16, 1899 was provided to me by Steven LoRocco, Esq. President of the San Rocco Society and Chairperson of the annual San Rocco Procession at St. Anthony’s Church. This article specifically identifies the San Felesi celebration of the Ma Donna Di Pierno, Pierno being a small hamlet within the commune of San Fele.

“Little Italy, which really consist of a number of Little Italys scattered in various quarters of the city, was en fete yesterday. The Feast of the assumption takes rank in the Latin countries with Christmas and Easter, and the Italians in New York are extremely tenacious of their customs, though their storekeepers did not shut up their shops yesterday. Their reverence of the established institutions of their people fell just short of that. But in every other respect the day was as faithfully observed as in the sunny land across the sea.

Mulberry Street, Elizabeth Street, Mott Street and the other thoroughfares which have been appropriated by the Italians were decorated with a profusion only equaled in Chinatown on the Celestials New Year’s Day. There were American and Italian flags galore; paper lanterns hung from windows and fire escapes and festoons of little glass lamps were strung across the streets. The effect, especially after nightfall, was an extremely picturesque one. The decorations, with very few exceptions, were of the cheapest character, but a few cents spent in bunting and colored paper go a long way, and many an elaborate and costly “color scheme” has been less successful in its result.

The great event of he day, however, took place in the morning, when the members of the “Congrega Assunta di Pierno” marched in procession from Pearl Street to the little Italian Church at Tillary and Lawrence Streets, Brooklyn. The Society of Pierno is one of the most venerable institutions in existence. Founded in that tiny town hundreds of years ago, it has branches in every city in Italy and others all over the world. The new York branch is one of the largest, and among its members are the rank and wealth of the Italian colony here. It has a wonderfully embroidered banner, said to have cost $500, on which is pictured the ancient town of Pierno, with its white walls and background of olive crowned hills. The procession was headed by a band, and those who marched in it wore costumes almost as gorgeous as the banner itself. The route was through Mott Street, Broome Street, Mulberry Street, Baxter Street, Canal Street, Back to Mulberry Street, and then across the Bridge to Brooklyn”.

As you can see from the previous two articles the writers don’t know quite what to make of the festivals. However, they were beginning to attract attention if not understanding. Mr. Riis, a writer and photographer of the period wrote an article for “The Century Magazine” in August 1899 relating an earlier experience. The article is titled “Feast-Days in Little Italy” and relates to an earlier observance of the Feast of St. Donato which occurred the day after the San Rocco and Di Pierno celebration of 1895. The participants are Lucani from the village of Auletta which neighbors san Fele. Mr Riis was in the Five Points in the company of the newly elected President of the New York Police Commissioner Board, Theodore Roosevelt.

“The rumble of trucks and the slamming of boxes up on the corner ceased for the moment, and in the hush that fell upon Mulberry Street snatches of a familiar tune, punctuated by a determined drum, struggled into the block. Around the corner came aband of musicians with green cock-feathers in hats set rakishly over fierce, sunburnt faces. A raft of boys walked in front, abreast of two bored policemen, stepping in time to the music. Four men carried a silk-fringed banner with evident pride. Behind them a strange procession toiled along: women with babies at the breast and dragging little children; fat and prosperous padrones carrying their canes like staves of office and authority; young men out for a holiday; old men with lives of hardship and toil written in their halting gait and worn and crooked frames; lastly, a cripple on crutches, who stove manfully to keep up. The officials in the Police Headquarters looked out of the window and viewed the show indifferently. It was an every-day spectacle. This one had wandered around the lock thrice that day. President Roosevelt (of the Police Board), who had come out to go to lunch, was much interested. To him it was new.

“Where do you think they are going?” he said, surveying the procession from the steps. He was told that some Italian village saint was having his day celebrated around Elizabeth Street, and he expressed a desire to see how it was done. So we fell in, he and I, and followed the band too, at a little distance.”

From this article it is clear that the Italian community and its customs were largely unfamiliar to almost all Americans of the era.

The last article I will include is from the New York Times August 16, 1905 article titled, “Two Great Festivals Keep Italians Busy”. The article is about the San Rocco festival and the Ma Donna Di Pierno Festival although the reporter uses the name Our Lady of Perpetual Succor which is one of the many names that an image of Ma Donna and Child is known by. The article begins to indicate that the two festivals were conducted at the same time within the “Little Italy” community.

“All the things that tell of a holiday season among the Italians were seen in the various Little Italies of New York yesterday. Red and white and green flags were strung along the streets. Thick in the districts were the improvised stands where are for sale long strings of big and little chestnuts and sliced cake. At central points were the inevitable altars and the inevitable band stands. The people had on their gayest clothes. Strung across the streets were hundreds of red and white and green jelly glasses.

When night came on an official went about with a basket full of little tin cans with oil and thick a thick wix in them, dropping one in each glass. It required a world of patience for this man and his subordinates to keep all the lighting going. They didn’t last the night.

Two festivals were begun yesterday, and they will continue two or three days and nights, according to how often the rain interrupts the ceremonies. Some Italians are celebrating the Feast of san Rocco who is reputed to have done great works for good in the cholera epidemic in their section of the home land. Italians from other sections of the oldcountry are celebrating the Feast of Our lady of Perpetual Succor.

In the Little Italy along Mott and Elizabeth Streets, near Houston and Broome Streets, the twin celebrations were in intermittent blast yesterday. For the rain stopped the exercises now and then.

The Societa San Rocco has a high alter in Mott Street, near Houston Street, with bandstands and chestnut stands. On Monday night the $1,800 statue of San Rocco was installed in its shrine. That night four young Italians knocked down and robbed a young Finn named Victor Correndes of Brooklyn near the shrine and placed part of the swag upon the alter as a votive offering. The four wicked Italians, of course, were arrested by detectives Simonetti and Dolan of the Oak Street Station. The Finn found his citizenship papers near the statue.

“My vote, my vote, it’s found!” he yelled in ecstacy. And then he was satisfied. He didn’t care about anything except his “vote”.

Fearing that the rain would do damage to the statue the officers of the San Rocco Society moved it yesterday morning into the nearby undertaking establishment of La Vecchia and Marasco. But it will be brought out again to-day. This wooden statue, which was bought by a man of the very name of Rocco, is about four feet in height.

The Societa San Rocco held services yesterday morning and last night in St. Patrick’s Pro-Cathedral, just across the street from the altar. Asked if St. Patrick was an Italian saint, an Italian answered: “No, he Irisha; they gone long ago when we come in an’ we taka da church.” New York’s population shifts a lot.

Assisting the Societa San Rocco today and tomorrow will be the following societies: San Michele, Santa Margarita, La Sinta Societa, and the San Antonio Society of Newark. There will be much marching and parading, and five bands, it is told, will furnish the music. The posters say that to-night there will be “ di fuochi di artificiati” as well as an “ illuminazione fantastica, a concerto musicale”.

Near Elizabeth and Broome Streets was the shrine and statue of Our Lady of Perpetual Succor. The festival in her honor is carried on by the Society of the Assumption of Pierno, which had a long parade yesterday to the Church of the Most Precious Blood, near Baxter Street. Last night this society lighted a wealth of fireworks in the Harry Howard Square.

The Elizabeth Street statue of Our Lady of Perpetual Succor is about half as big as that of San Rocco, but its shrine is almost as gorgeous. Jupiter Pluvius, in spite of his Latin name, acted shamefully toward these shrines yesterday. When he got through the papier mache’ figures and gilded trimmings of the shrines were pathetically bedraggled things.

Before the Elizabeth Street statue late yesterday afternoon there stood more than a dozen candles, varying in size from twelve-inch cannon size to that of a stick of candy. But all were yellow, and were painted gorgeously. In spite of the early rain flurries the candles were kept lighted all day long. Burt it was a difficult thing to do, as they were open to the sky.

There came a heavy downpour of rain late in the afternoon. The devout Italians huddled about the candles, shielding them with their bodies and their umbrellas. One by one they all winked out except one huge yellow candle that stood five feet high. The crowd watched that intently. A huge spat of rain struck the wick, but the light struggled up weakly. The noise of the coming fierce flurry of rain made them all hang tense around the one lighted candle.

“Pooh!” came a significant blowing-out sound from the inner circle, and the crowd groaned. A little youngster of twelve rushed out with his eyes ablaze.

“It shalla not die out; we put it out ourselves,” he screamed in apology.”

I think the above articles give a representative taste and flavor of some of the attitudes and conditions faced by these early Italian immigrants. It also reflects how foreign and odd their customs appeared to the larger American community. Unfortunately, that lack of understanding sometimes is projected in an unflattering, derogatory and or prejudicial way.

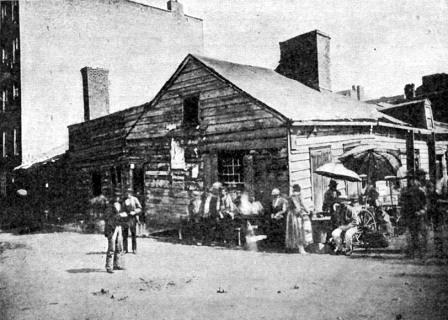

Photographs by Jacob Riis

Jacob Riis was a writer and photographer who at the end of the 19th century published a work entitled “ How the Other Half Lives”. Some of the many photographs he took and included were of the late 19th century “Five Points” community. These present a visual history of the conditions that our early immigrant ancestors lived in before the great surge of immigration 1906-1925. The original photographs can be viewed at the New York Museum in Manhattan. Below is a photograph looking further up Mulberry Street from the point of the “Bend” as it would have appeared in the 1890’s.

Photograph J. Riis from “How the Other Half Lives”

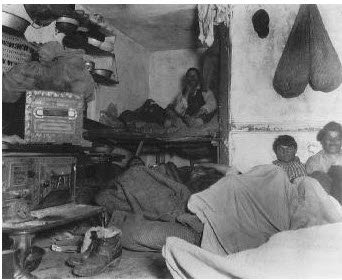

As previously described the living conditions that these immigrants endured to succeed is hardly imaginable to us today. Below is a Riis photograph of a typical “Five Points” tenement sleeping arraignment in the late 19th century. While it is difficult o discern there are between five and seven men huddled together in this picture.

J. Riis Photo “How the Other Half Lives” Bayard Street tenement house.

The “Five Points” section of New York may have been one of the few places the newly arrive poor Italian immigrants could afford to live however it was not a welcoming, friendly or safe environment. Italians clustered together for mutual protection. They were in this environment foreign, unwelcomed competitors and Catholic. To get a feel for the environment watch the movie “Gangs of New York”, this is the environment of the Five Points these folks moved into. As their numbers increased they did as one article described “appropriate” more and more streets. The photograph below shows an ally off of Mulberry Street known for decades as “Bandits Roost”. At the time Riis took this photo the area had been appropriated by Italians. You will note that the Italian men standing about are “armed” some with shotguns.

Photo J. Riis “How the Other Half Lives” Bandits Roost.

In contrast to the above photograph is the one below. Taken in the same spot in the same year the second photograph shows how the community transformed for the feast of San Rocco and the Ma Donna in August. Note that the men have receded in the background, young children are out at night in their best clothes and a small shrine is set at the end of the ally.

Photograph J. Riis, “How the Other Half Lives” Bandits Roost, feast of San Rocco.

The next photograph shows a more domestic scene. Jersey Street in the Five Points saw a number of Italian Immigrants employed as “rag-pickers”. In the photograph you see a mother and child at home on Jersey Street. Infant mortality was several times as high in the Five Points as any other part of New York City and the highest in the US at the time.

Photograph J. Riis, “How the Other half Lives”. Photo is titled “ In the home of an Italian rag-picker, Jersey Street”

100th Anniversary: Arrival of the Sisters of the Filippini Order

Our San Felesi community joins in the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the arrival of the Sisters of the Filippini Order in America. Our society extends our warmest congratulations and gratitude for a century of service to the parish and parishioners of St. Joachim’s Church of Trenton, NJ and for the service to the many people and parishes throughout the country which continue to be served by the good works of the Order. Those first Nuns of the Order who arrived in Trenton August 10, 1910 and provided both religious and academic instruction began a tradition of service to generations of children in Trenton. We are all extremely grateful and our prayers and thanks are extended to all of the Order. The San Felesi are proud of their leadership role in helping bring about the parish of St. Joachim’s in 1901 and in supporting the arrival and mission of the Filippini Order since 1910. The support of education being evident in the community from the first day as San Felesi lead the parade of welcome down Bulter Street on that first August day in 1910.

Education has always been important to the Lucani /San Felesi as it is to all Italians. Even under the most difficult of conditions education was encouraged and supported as Italians immigrated to the United States. Conditions often did not lend themselves to academics but many Italians took the time to make sure their children would receive a good education. We all know that sometimes that lead to them sacrificing their use of Italian in the home in order to force their children and themselves to communicate in English. Again, looking through those 19th century photographs from the Five Points I was struck by one in particular. In the photograph below a father and young son living in the squalor of Jersey Street on rag-pickers row taking the time to instruct and learn.

Photo J. Riis, “How the Other Half Lives” entitled “Pietro learning to write”.

© San Felese Society of New Jersey